From unflinching portrayals of racial hatred to hard-hitting invective against injustice, demands for equality, and even stadium anthems with a subversive message, the best protest songs speak not only to the issues of their times, but transcend their eras to become timeless political expressions. Hip-Hop arguably remains the most politically engaged music of our current era, but, throughout the decades, jazz, folk, funk, and rock music have all made contributions to the best protest songs of all time.

Many more can lay claim to a place in this list. Think we’ve missed your best protest songs? Let us know in the comments section, below.

While you’re reading, listen to our Protest Anthems playlist here.

Billie Holiday – Strange Fruit (1939)

Written as a poem by Abel Meeropol – a white, Jewish teacher and member of the American Communist Party – and published in 1937 before he set the lines to music, “Strange Fruit” exposes the sheer brutality of racism in the United States at the time by way of a stark, powerful description of a postcard Meeropol had seen depicting a lynching. Juxtaposing idyllic, florid scenes of a Southern landscape with uncompromising descriptions of black bodies swaying from a tree in the Southern breeze, his words were blunt and had the desired effect of shocking and appalling listeners.

When Billie Holiday first began performing the song at Café Society, in 1939, she was afraid of retaliation. But “Strange Fruit” became a show-stopper – quite literally. A rule was enforced that she’d only be able to perform it as the last song in her set, once the bar staff had called time and the room was darkened. Holiday grasped the impact the song had and knew she had to record it, but when she approached Columbia, her record label, they feared repercussions and gave her permission to record it for another label. Commodore stepped in and released Holiday’s version, which went on to sell a million copies, spreading awareness of the unmentionable cruelty and suffering caused by racism. However, many times it’s heard, “Strange Fruit” still feels like a warning from a not-too-distant past. – Jamie Atkins

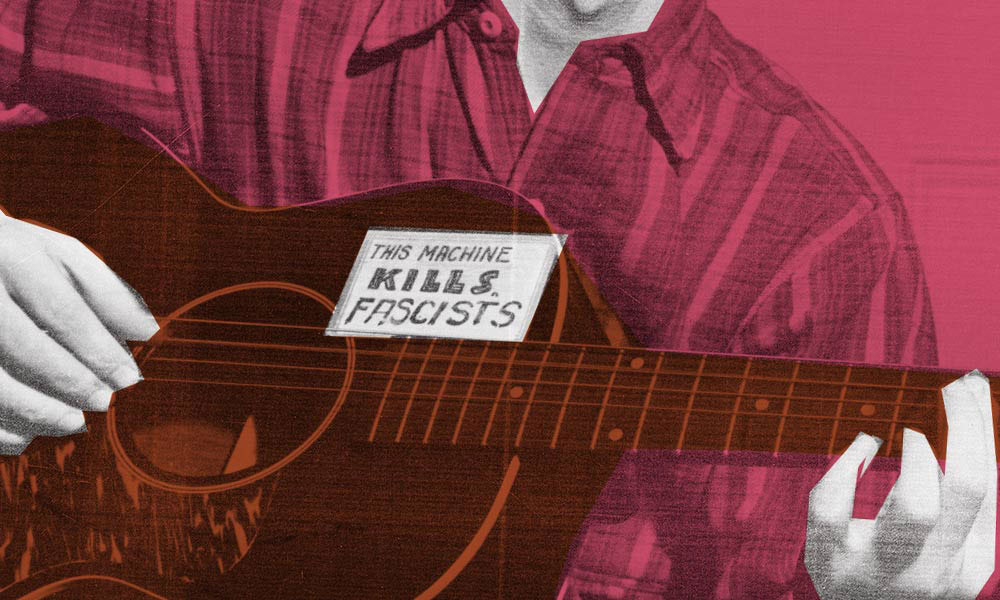

Woody Guthrie – This Land Is Your Land (1944)

It’s remarkable to think that a song as entrenched in the American psyche as Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” started life as an answer song. Guthrie had grown increasingly irritated with what he considered to be the smug complacency of Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America”(inescapable in the late 30s, thanks to radio playing Kate Smith’s version) and crafted a retort that celebrated the natural beauty of the United States while questioning the notion of private ownership of property and pointing out the problem America had with poverty and inequality. He based the tune on The Carter Family’s “When The World’s On Fire” (itself derived from the Baptist hymn “Oh, My Loving Brother”) and called it “God Blessed America.” Originally, rather than each verse ending with, “This land was made for you and me,” Guthrie had written, “God blessed America for me.”

Guthrie recorded the song as a demo in 1944, changing the title and omitting the most explicitly political verse. Still, “This Land Is Your Land” gradually gained momentum as it was adopted as a patriotic anthem, and sung around campfires, at rallies, and in schools across the US. As with the best protest songs, it still resonates: Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen’s moving rendition at President Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration ceremony remains a testament to its enduring power. – Jamie Atkins

Bob Dylan – Masters Of War (1963)

While plenty of Dylan’s early forays into politicized writing leave room for interpretation, “Masters Of War” sees the then 21-year-old at his most pointed. On the release of its parent album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, he told Village Voice critic Nat Hentoff, “I’ve never really written anything like that before… I don’t sing songs which hope people will die, but I couldn’t help it in this one. The song is a sort of striking out, a reaction to the last straw, a feeling of what can you do?”

It’s an angry song, the young Dylan obviously incensed by a feeling of helplessness as the United States became entangled in international affairs – Cuba, Vietnam – for reasons he considered to be self-serving. In a 2001 interview with USA Today he explained it was “supposed to be a pacifistic song against war,” adding, “It’s not an anti-war song. It’s speaking against what Eisenhower was calling a military-industrial complex as he was making his exit from the presidency. That spirit was in the air, and I picked it up.”

He certainly did. Dylan had an uncanny ability for tapping into the zeitgeist, penning some of the best protest songs of the 60s and beyond, including “Maggie’s Farm” and “Hurricane.” Despite its venomous ire, “Masters Of War” has been covered by plenty of artists from The Staple Singers to Cher. And its impact hasn’t dulled; it was even covered by Ed Sheeran in 2013 for the ONE Campaign against global poverty. – Jamie Atkins

Sam Cooke – A Change Is Gonna Come (1964)

This early 1964 track was a departure for Sam Cooke, who hadn’t previously addressed the Civil Rights Movement in his music. But the times were a-changing and he’d been inspired both by Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind” and Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. (Cooke wrote the song after his band was turned away from a whites-only motel in Louisiana.) Cooke had mixed feelings about the song, only performed it live once and resisted manager Allen Klein’s efforts to make it a single. It was eventually released, posthumously, and is now considered one of his more important records. – Brett Milano

Nina Simone – Mississippi Goddam (1964)

You can hear the moment on Nina Simone’s 1964 album recorded at Carnegie Hall: After winning the crowd with some show tunes she announces another show tune, “but the show hasn’t been written for it yet.” Then she launches into “Mississippi Goddam” and the laughing stops. Written in the wake of the murder of Emmett Till, Civil Rights activist Medgar Evers, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, the song is perfectly furious – but also perfectly tuneful, because she wanted the message to get heard. Phillips duly put it out as a single (changing the official title to “Mississippi *@!!?X@!”) causing some DJ’s to send back broken copies. Simone claimed her career was blackballed because of it, but she continued to record fiery and important music in the years following. – Brett Milano

Buffalo Springfield – For What It’s Worth (1966)

Though the song’s outlived the circumstances, this Stephen Stills landmark was inspired by a specific event: During 1966 the Sunset Strip police got impatient with hippie kids hanging around, and imposed a 10pm curfew – initially targeting the Whiskey a Go Go, where Buffalo Springfield were the house band. The result was two months’ worth of nightly riots, which prompted numerous songs and even a movie (Riot of Sunset Strip). Stills’ song aimed higher, catching the cultural changes of the moment and the bigger ones that were coming. – Brett Milano

Aretha Franklin – Respect (1967)

“Respect” certainly wasn’t a feminist manifesto when Otis Redding sang the original version, though Otis wasn’t anti-feminist either: In his version, his partner could do whatever she pleased with her time as long as she showed a little respect when he got home with the money. Aretha’s version is very much a demand to be treated right, and she slightly reworks the lyrics to give herself the upper hand: Whether it’s love or money, she has what the guy needs and he’d better earn it. – Brett Milano

James Brown – Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud (1968)

Though he’d changed the face of black music a few times by 1968, that year’s “Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud” was the first song on which James Brown made an overt statement on civil rights – and it was a typically mold-breaking way of making his feelings known. The tone of the civil-rights movement had so far been one of a request for equality. Brown, however, came out defiant and proud: he isn’t asking politely for acceptance; he’s totally comfortable in his own skin. The song went to No.10 on the Billboard charts and set the blueprint for funk. Like later Stevie Wonder classics of the 70s, it was a political song that also burned up the dancefloor; an unapologetic stormer that would influence generations. – Jamie Atkins

Creedence Clearwater Revival – Fortunate Son (1969)

Few political songs have been subject to more misunderstanding than John Fogerty’s Vietnam-era treatise. Most everyone got what Fogerty meant in 1969: The song pointed a finger at the class-centric nature of the draft system, calling out the “senator’s sons” who managed to avoid service. (A President’s grandson, David Eisenhower, apparently inspired it.) The chorus of “It ain’t me!” was duly embraced by young men who couldn’t duck the draft. “Fortunate Son” later showed up in many commercials, however, and Fogerty was none too pleased when the song was used at political rallies by Donald Trump. – Brett Milano

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – Ohio (1970)

While the old saying claims that a picture is worth a thousand words, in the case of a photograph taken by student John Filo and later printed in Life magazine, a picture also inspired one of the best protest songs of its time. The photograph was taken in the immediate aftermath of the Ohio National Guard opening fire on students protesting the Vietnam War at Kent State University, on May 4, 1970, and captures protester Mary Vecchio kneeling aghast and open-mouthed over the body of student Jeff Miller at the moment she realizes what has happened.

When Neil Young saw the photo he was appalled enough to take a guitar handed to him by David Crosby and pour his anger into a song. “Ohio” drew an us-and-them line in the sand, with lyrics such as “Soldiers are cutting us down/Should have been done long ago” reflecting the anti-student-protest sentiment among factions of the US public. The recording by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young made it even more powerful: a heady, simmering brew of a song that comes to a head towards the end with David Crosby’s appalled, passionate cries of “Why?” Only the very best protest songs transcend very specific subject matter to become universal – and “Ohio” does exactly that. – Jamie Atkins

John Lennon – Imagine (1971)

John Lennon’s political protest songs weren’t always this hopeful; on the same album with “Imagine” were the pure venom of “Gimme Some Truth” and the dread of “I Don’t Want to Be a Soldier Mama, I Don’t Wanna Die.” But he was also the man who wrote “All You Need is Love,” and his idealistic side came through on a song that dares you to imagine a world without war, possessions, or religion. He’d be glad to know that decades later, despite everything, we’re still imagining it. – Brett Milano

Gil Scott-Heron – The Revolution Will Not Be Televised (1971)

“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” has become such a catchphrase that first-time listeners may be surprised by the amount of righteous and still-relevant anger in this political song by Gil Scott-Heron. With its rapid-fire references to 70s commercials and shows, it’s partly a response to what Scott-Heron saw as the shallowness of TV and its failure to meet the Black experience. Musically it’s an homage to the jazz poetry of The Last Poets, who like Scott-Heron are now recognized as progenitors of rap. There were actually two versions, the 1971 album track (with only voice and congas) and the 1974 single remake (now on most compilations). The latter is the keeper, with drummer Bernard Purdie and flutist Hubert Laws lending a profound funk groove. – Brett Milano

Marvin Gaye – What’s Going On (1971)

Marvin Gaye’s masterpiece is less a protest than a song of healing; he claimed at the time that he recorded it to help humanity and himself, and to restore a sense of peace. But the song’s origins aren’t peaceful; it was born after Four Tops member Ollie Benson witnessed police brutality against antiwar protesters in Berkeley; he and Motown staffer Al Cleveland wrote the song which Gaye substantially reworked. The reference to protests and brutality stayed in, but in Gaye’s hands the song became a plea for understanding, with his beatific “right on’s.” – Brett Milano

The Wailers – Get Up, Stand Up (1973)

Written by Bob Marley and Peter Tosh after they witnessed poverty and oppression in Haiti, “Get Up, Stand Up” is one of the most rousing anthems in reggae. But it would be a mistake to take it as a simple song of empowerment: The lyrics call out the oppressive nature of organized religion, and say that instead of waiting for a heavenly reward, you need to demand yours right now. In the third verse of the original version, Tosh dares the downpressors to do something about the wisdom he’s just spread. – Brett Milano

Robert Wyatt – Shipbuilding (1982)

When producer Clive Langer played Elvis Costello a jazz-inflected piano tune he’d been struggling to find suitable lyrics for, the 1982 conflict between Britain and Argentina over the Falkland Islands had just begun. Costello’s lyric for what would become “Shipbuilding” considers the potential repercussions of the conflict on the traditional ship-building areas of the UK, then in decline. The song ponders whether the reversal of fortunes for the shipyards could ever be weighed up against the potential losses in terms of casualties of war (“Is it worth it?/A new winter coat and shoes for the wife/And a bicycle on the boy’s birthday”) and takes a sensitive, nuanced look at the choices people make when their hands are tied (“It’s all we’re skilled in/We will be shipbuilding”). The political song was written with Robert Wyatt in mind, and he sings it beautifully, his plaintive vocals perfectly complementing the conflicted lyric. Wyatt later suggested that the song could be read as “the way the conservative establishment glorifies the working class as ‘our boys’ whenever they want to put them in uniform.” – Jamie Atkins

The Specials – Free Nelson Mandela (1984)

Proving that political songs can simultaneously sway hips and broaden minds, Jerry Dammers’ (founder of the English ska band The Specials) “Free Nelson Mandela” was a joyous-sounding, upbeat dancefloor hit that became the unofficial anthem for the international anti-apartheid movement. It’s remarkable that a song with such an uncompromising, clear political message was a hit, but in the UK, “Free Nelson Mandela” reached No.6 in the charts while becoming immensely popular elsewhere in the world, including South Africa.

When the song was released, Mandela had already been in prison for 20 years on charges of sabotage and attempting to overthrow the South African government, but the song claimed its place among the best protest songs of the 80s, raising both Mandela’s profile and his cause that bit higher and reaching those who might not have been engaged enough with world issues to be familiar with his story, inspiring them to learn more. On Mandela’s release in 1990, “Free Nelson Mandela” was everywhere: an uplifting ode to freedom. – Jamie Atkins

Bruce Springsteen – Born In The USA (1984)

While the Born In The USA album pushed Bruce Springsteen to a new level of superstardom in his homeland, many missed the not-so-subtle undertones in the triumphant-sounding title track. Springsteen’s original version of the song, a spooked, solo rockabilly rattle recorded during the sessions for 1982’s Nebraska, better reflects the tone of the lyrics. It’s the story of a Vietnam veteran having trouble adjusting to civilian life and feeling stranded by a lack of government support.

Still, the version that became a fist-pumping anthem for those who didn’t properly listen might be more effective, in that the song became something subversive, reaching audiences it would never have been able to in its original guise. – Jamie Atkins

Public Enemy – Fight The Power (1989)

Following the 1988 release of their groundbreaking album It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back, hip-hop pioneers Public Enemy were the hottest group on the planet – outspoken, musically thrilling, and with a mainline connection to what was happening in black America. Filmmaker Spike Lee was in much the same position after writing and directing She’s Gotta Have It and School Daze, films that spoke unapologetically to a young black audience.

When Lee was writing his hotly anticipated Do The Right Thing, a film that explored racial tensions on the streets of New York City, he knew the soundtrack had to include Public Enemy. According to Hank Shocklee, of the group’s production team, The Bomb Squad: “Spike’s original idea was to have [us] do a hip-hop version of “Lift Every Voice And Sing,” a spiritual. But I opened the window and asked him to stick his head outside. ‘Man, what sounds do you hear? You’re not going to hear “Lift Every Voice And Sing” in every car that drives by.’ We needed to make something that’s going to resonate on the street level.”

And they did. “Fight The Power’”s explosive collage of funk, noise and incendiary beats provided a backdrop to immediately iconic lyrics from main man Chuck D and co, among them, “’Cause I’m black and I’m proud/I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped/Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps.” Chuck acknowledged that the song was their most important, playing a huge role in capturing the social and psychological struggles facing young black Americans at the time. – Jamie Atkins

Kendrick Lamar – Alright (2015)

In the lead-up to the March 2015 release of Kendrick Lamar’s landmark album, To Pimp A Butterfly, the United States was suffering a period of serious civil unrest. In November 2014, the decision not to indict the police officer who fatally shot Michael Brown ignited protests and riots across the country. That same month, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot and killed by police after being spotted holding a toy gun. The Black Lives Matter movement was gaining momentum daily and, on the release of To Pimp…, the song ‘Alright’, with its plea for hope through solidarity and resilience, was adopted by supporters of the cause.

“Alright” rapidly became a bona fide anthem, one of the best protest songs of its era, demonstrating the importance that social media plays in spreading the word. Video footage of protesters gleefully shouting Kendrick’s refrain of “We gon’ be alright” was shared around the world, underlining the influence that music still has on politics. – Jamie Atkins

Donald Glover/Childish Gambino – This Is America (2018)

Few songs on this list got people talking as fast as this one did when its video dropped in early 2018. By now everybody knows about its apocalyptic symbolism and its shocking echo of the Charleston shooting. By debuting this video just after playing Saturday Night Live (where he did a straight-up live version of the song), Glover gave the country a chilling wake-up call – and did it with a track that might otherwise have been mistaken for a slightly ominous party song. – Brett Milano

Honorable Mention

Tracy Chapman – Talkin’ ‘Bout a Revolution

Beyoncé ft. Kendrick Lamar – Freedom

Barry McGuire – Eve of Destruction

N.W.A. – F— Tha Police

Country Joe and the Fish – I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag

Looking for more? Discover the most misunderstood political songs of all time.