“Something got broken like glass,” said Robbie Robertson of The Band’s problems in the early 70s. Signs of the impending break-up had been evident during sessions for their fourth album, 1970’s Stage Fright – “We all realized something was wrong, that things were beginning to slide,” admitted drummer Levon Helm – and by the time the five members (Robertson and Helm were joined by Garth Hudson, Rick Danko, and Richard Manuel) turned up at the newly-opened Bearsville Sound Studio in New York to record their fourth album, Cahoots, drug, and drink-filled emotions were close to breaking point.

“There was a feeling of pulling teeth,” Robertson later said of those Bearsville sessions in the early months of 1971, “it was painful… it was hard for me to write under those circumstances.” The musicians did not like the atmosphere at Albert Grossman’s new recording facility near Woodstock, judging it to be “too bright and cold” to be conducive to recording their brand of flowing Americana music.

When the album was released by Capitol Records on September 15, 1971, it was met with mixed reviews but has only grown in appreciation over the years. Rolling Stone magazine’s John Landau presciently described Cahoots as being “filled with a tinge of extinction,” because The Band did not release another album of original material for four years, until 1975’s Northern Lights – Southern Cross.

The first of the 11 tracks on Cahoots was a cracker. “Life Is a Carnival” – co-written by Helm, Robertson, and Danko – features a brilliantly funky New Orleans sound, much of which is down to the sparky horn arrangements by Alan Toussaint. Although the brass section went uncredited in the liner notes for Cahoots, Toussaint brought in some top-class players for the track.

The Band were so happy with the final version that they later recorded a whole live set, called Rock of Ages, featuring Toussaint’s arrangements, when the backing musicians included trumpet master Snooky Young, a veteran of Lionel Hampton and Count Basie bands. The song “Life is a Carnival” was a celebration of circus life, a subject dear to the heart of Helm. Musical notation for this composition is printed on a wall behind his grave in Woodstock.

Helm took lead vocals on the second track, a mournful, respectful cover of long-term collaborator Bob Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” which features some fine accordion playing from Hudson. Helm played mandolin, and Manuel moved to drums for the track.

The Band played an integral role in changing the direction of American music with their 1968 masterpiece Music from Big Pink, an album for which Manuel wrote three of the songs. By the time of Cahoots, however, Manuel had lost his enthusiasm for songwriting, leaving Robertson to shoulder most of the lyric-writing duties. The singer/guitarist wrote eight of the 11 songs on Cahoots, including such as “Last of the Blacksmiths” and “Where Do We Go From Here?,” a piercing study of the threat of extinction, which included the haunting lines:

“Have you heard about the buffalo on the plain,

And how at one time they’d stampede a thousand strong.

And now that buffalo’s at the zoo standing in the rain,

Just one more victim of fate,

Like California state.”

The final track on Side One of Cahoots was the raucous “4% Pantomime,” which is certainly one of the most interesting songs on the album, and one Robertson co-wrote with Van Morrison. The Irish singer, who was then living near Woodstock, stayed in the studio to sing it as a duet with Manuel. In his 1993 memoir, This Wheel’s on Fire Levon Helm and the Story of the Band, Helm said that Morrison dropped in at Bearsville and started chatting about whisky and various alcohol content in Johnny Walker’s Red and Black label bottles (the percentage formed part of the song’s title).

In what Helm called “an extremely liquid session,” Morrison and Robertson penned a song about the problems of music management and the joys of booze. In the final version, Manuel sings about Morrison’s nickname in the lines, “Oh, Belfast Cowboy, can you call a spade a spade?” Robertson said the musicians all had fun making that “wild and bizarre” track.

Side Two opens with “Shoot Out In Chinatown,” featuring shared vocals by Manuel, Danko, and Helm, which was about the disbandment of San Francisco’s Chinatown police force. The Band tried to get jazz legend Gil Evans, famed for his work with Miles Davis and Kenny Burrell, to write arrangements for “The Moon Struck One,” and were hugely disappointed when scheduling problems ruled this out. The best thing about the version they produced without Evans is Hudson’s keyboard work. Manuel took over piano duties for “Thinkin’ Out Loud,” and he absolutely shines on this song about life on the road for a touring band.

The final three tracks were “Smoke Signal,” “Volcano” – which was arranged by Danko, who took lead vocals on the track – and “The River Hymn,” on which Libby Titus, Helm’s girlfriend at the time, sang backing vocals on a touching, religion-inspired composition. It was the first time a woman had appeared on a Band album. Titus, later the subject of the tribute song “Pretty Libby” by partner Dr. John, went uncredited in the liner notes, although there was a name check for the Band’s regular engineer, Mark Harman.

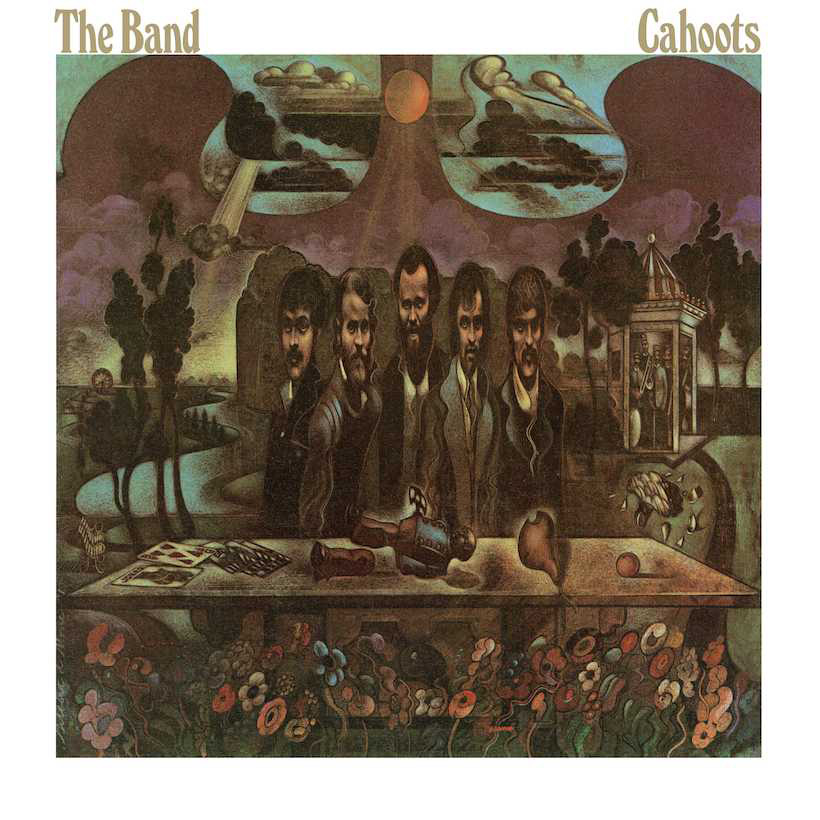

Cahoots (which was reissued in 2000 and included a tribute song to Bessie Smith and a version of the Holland-Dozier-Holland classic “Don’t Do It”) remains an important part of The Band’s story, and one that came at a time when the group was clearly fracturing. The album also featured a beautiful cover illustration, courtesy of the late New York artist Gilbert Leonard Stone and the moody back cover photograph was taken by Richard Avedon.

The Band’s fourth album is more than just one for completists. Cahoots is an interesting mix of moods and tones, and an album that found favor with the public. It reached No.21 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, and it continues to be an album that grows on fans of a group who wrote the blueprint for Americana.