To paraphrase Tom Jones, it’s not unusual for anyone to make a great album – even two great albums – that don’t sell. It’s not unusual when that artist disappears after those albums flop. What is unusual is when those albums get rediscovered, making the artist an international star some four decades after the fact. That is why the story of Sixto Rodriguez is so inspiring.

Searching for Sugar Man

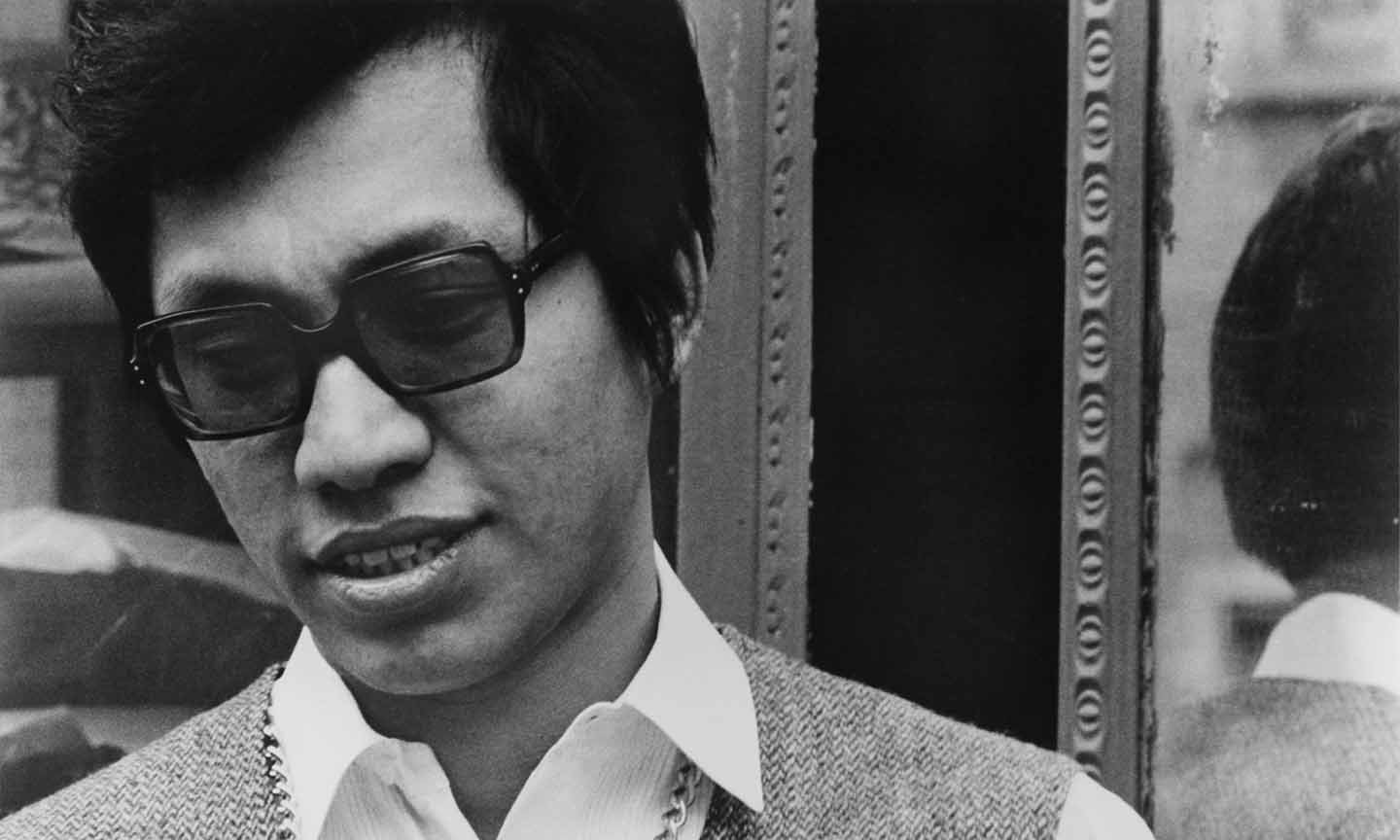

Thanks to the 2012 award-winning documentary Searching For Sugar Man, the story of Rodriguez is now a familiar one. The Detroit-based singer-songwriter releases two albums on the LA-based label Sussex Records in 1970 and 1971, respectively, which then somehow find their way to South Africa as imports long after the US versions have been deleted. Thousands of copies get bootlegged and the music touches a chord, not least because the anti-racist sentiments of some lyrics translate well to the anti-apartheid movement. Even anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko apparently owned copies, and you can’t ask for a better endorsement than that. Yet nobody knows who or where Rodriguez is. Rumors spread that he’d died in some spectacular way, and a few fans set out to discover the truth…

A rediscovery

Then the late Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul comes along and documents the efforts of two Cape Town fans to track Rodriguez down. He is, of course, not dead, just living quietly in the Detroit area, where he’s probably the only resident without a cell phone or an internet connection. Rodriguez comes to South Africa for a triumphant show, which provides the emotional climax of Bendjelloul’s movie Searching For Sugar Man.

For most of the world, however, Rodriguez’s rediscovery happens because of the movie itself. The director wisely focused on certain songs throughout the film, making sure the most memorable ones got heard more than once. “Sugar Man” and “I Wonder” dealt with the still-resonant topics of the drug trade and sexual jealousy, and anyone seeing the film would come away with those songs in their head.

A well-chosen soundtrack album (combining songs from the two studio albums, Cold Fact and Coming From Reality, plus a couple of outtakes) charted worldwide. The film won the Best Documentary Oscar in 2013 and Rodriguez toured nationally over the next several years, playing the early-70s material to an audience that never heard it the first time around.

Overshadowed in the 70s

But if Rodriguez was so good, why did his records initially flop? One possible explanation is that his label, Sussex, simply had its hands full: their star artist was Dennis Coffey, the great Motown guitarist who was then hitting with solo instrumentals while producing Rodriguez on the side (hence the psychedelic-soul flavor to Rodriguez’s albums). But the label had just signed another soulful, largely acoustic artist who perhaps had a little more star potential: Bill Withers. Or it could be because the pop world in 1971 was too much an embarrassment of riches?

For black music, this was the year of two game-changers: Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and Sly And The Family Stone’s There’s A Riot Going On. Rockers had Who’s Next and The Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers to take in, and the songwriting world was about to be shaken up by a not-so-young upstart named David Bowie. In a climate of wall-to-wall brilliance, listeners were likely to greet a street poet like Rodriguez with a “been there, done that” kind of shrug. Brilliant songwriting was no longer enough to guarantee an audience, just ask Nick Drake (if you could), Judee Sill or Arthur Lee, whose masterpieces were also flying under the radar.

What the film missed

But as many viewers have pointed out, the movie got one thing wrong. He may have been obscure, but Rodriguez wasn’t completely ignored over the years. His songs were getting covered as early as 1977, the first artist to do so being Susan Cowsill, the former child star (and future member of Continental Drifters) who was then beginning a solo career. Rodriguez’s “I Think Of You” was the A-side of Cowsill’s single “The Next Time That I See You,” but it didn’t end up charting well. As a result of her interest, however, Cowsill’s current musical partner and husband, ace New Orleans drummer Russ Broussard, was part of the post-comeback tours Rodriguez did with a backing band.

It’s also true that Rodriguez’s international discovery began long before the film was made. It really began in Australia, where he toured successfully behind a compilation album, Rodriguez At His Best. This was the album most often counterfeited in South Africa, where Rodriguez first toured in 1998, putting those death rumors to rest. When he played there for the documentary, then, it was largely for an audience that already knew he was back. Meanwhile, in the US, Rodriguez albums were first reissued by the collector-friendly label Light In The Attic, three years before the movie’s release.

Wisdom from another era

It’s true, however, that hardly anyone in America heard Rodriguez before the release of the film: one of those quirks that makes pop culture so fascinating. Suddenly, listeners had a chance to discover an early-70s body of work and to hear it fresh, with no nostalgic associations.

Rodriguez’s trademark blend of folk and soul may have been considered low-key at the time of their release, but now sounded more familiar. It was no coincidence that Dave Matthews had been covering “Sugar Man.” The Detroit songwriter’s warnings about racism and political corruption (plus the jabs at hippie culture he took in songs like “A Most Disgusting Song”) may have been old news in 1971, but at the time of his rediscovery, they played as words of wisdom from another era.

Rodriguez’s two seminal 70s releases, Cold Fact and Coming From Reality, have been reissued on vinyl and can be bought here.