There’s a brilliantly funny scene in Tom Stoppard’s play The Real Thing, where the character of Henry, an intellectual playwright, is invited to select his favorite music for BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs programme. Henry’s dilemma is over whether to choose the sort of music that he thinks his audience would respect him for, or whether to be honest and choose the pop music that he loves. “You can have a bit of Pink Floyd shoved in between your symphonies and your Dame Janet Baker,” Henry muses, “that shows a refreshing breadth of taste, or at least a refreshing candor – but I like Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders doing ‘Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um.’”

For an industry where image is key, pop music itself has got an image problem of its own. Many critics view it with disdain, while even fans of one sort of pop music consider other types of pop music to be beneath contempt – valueless and not worthy of being considered music, let alone art. But this is nothing new. In fact, this is a problem as old as pop music itself. For as far back as you care to look, poor old pop music has been bullied, belittled, and sneered at: “It’s not art, it’s just pop.”

In order to determine whether pop music is art, it is first necessary to understand what pop music actually is. And it’s at this, the most fundamental of steps, that most arguments begin. To some, pop music is considered disposable. They see it as commercially driven music designed by big business to be marketable to a teenage (or younger) audience who, in their eyes, know no better. They think of pop as being music that doesn’t have the credibility to be described as “rock,” “folk,” “jazz,” “indie” – or any one of a hundred other labels. To them, pop is the lowest-common-denominator stuff that no self-respecting music fan would be caught dead listening to. Essentially, pop as a genre of its own. To others, however, pop might refer to any number of styles down the decades, from Frank Sinatra through Elvis Presley to The Beatles, Madonna, and countless other household (and underground) names. Others still might have an even wider definition, thinking of pop music simply as music that isn’t classical: a catch-all for anything contemporary. And then there are even those who don’t consider anything “pop” to be music at all. At which point, for fear of going round in circles, it’s worth exploring the history of the very idea of “pop music.”

What is pop music?

Humans have been making music for as long as they’ve been around – longer, even. A flute found in a cave in northwestern Solvenia in 1995 has been dated to somewhere around 40,000 years ago. Whether it was made by Neanderthals or Cro-Magnons continues to be debated, but what it does show is quite how long we – or our ancestors – have been enjoying music. Over the ages, of course, the style of music has changed unimaginably, with new instruments still being invented and developed today, along with new ways of playing them, varying ways of vocalizing, and so on, as people have become more sophisticated.

So at what point on the timeline of human existence does music become “pop”? Pop, after all, originated as shorthand for “popular music,” the sounds that were being dug by whatever generation in whichever society. The broadside ballads popular in Tudor and Stuart times are sometimes referred to by historians as “early pop music.” These bawdy, comical, and sentimental songs of the streets and taverns were pedaled on sheet music by street vendors, and proved popular with landed gentry as much as serfs in the fields. In Victorian times, audiences would enjoy concerts by the German-born composer Sir Julius Benedict, billed as the London Popular Concerts.

However, most music historians would agree that pop music, as we know it, began with the dawning of the recording industry. To help make customers’ choices easier, record companies would color-code music of different genres. In the immediate post-war years, RCA Victor, for example, sold classical music on red vinyl, country and polka on green, children’s on yellow, and so on, with black the reserve of ordinary pop, a genre that covered a multitude of things, but essentially meant “anything else.”

Of course, many of the musical styles that came under different headings – jazz, blues, country, and so on – was simply the pop music of the time and place from which they originated. Today, it’s widely accepted that early jazz musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald were artists of the highest caliber – likewise bebop musicians such as John Coltrane or Sonny Rollins. But at the time, many critics frowned upon such upstarts, leaping around with their blaring horns, making things up on the spot rather than sitting and playing notes that had been carefully written onto the page.

Similarly, blues musicians such as Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and Sonny Boy Williamson were considered not just inferior musically, but weren’t even treated equally as people in the racially divided United States. Today, their work is enshrined in Smithsonian museums and the Library Of Congress.

The rock’n’roll explosion

It wasn’t until the mid-50s that pop music began to actually mean something in its own right. With the explosion of rock’n’roll music, the pop business built itself an empire. The songwriters in New York’s legendary Brill Building crafted their art, with producers headed by Phil Spector delivering three-minute pop symphonies as rich and multi-timbred as Wagner at his height. (In the following decade, Brian Wilson’s production and songwriting expanded on Spector’s template; in 1966, Pet Sounds, marked a creative high point for both Wilson and The Beach Boys.)

But until the emergence of The Beatles, pop had remained largely ignored by critics on any intellectual level, with the music papers generally existing to describe new discs and inform the public and industry alike of goings-on. But in 1963, the renowned English music critic William Mann wrote about the Fab Four in The Times, in a manner previously reserved for high art: “One gets the impression that they think simultaneously of harmony and melody, so firmly are the major tonic sevenths and ninths built into their tunes, and the flat submediant key switches, so natural is the Aeolian cadence at the end of ‘Not A Second Time’ (the chord progression which ends Mahler’s ‘Song Of The Earth’).” He spoke of “lugubrious music” and “pandiationic clusters,” and achieved dubious notoriety when he called Lennon and McCartney “the greatest songwriters since Schubert.” People who would not have been pop music fans were starting to sit up and take it seriously – perhaps not yet going as far as to call it art, but nonetheless applying the same critical analysis that would be applied to the more traditional arts.

But although The Beatles were certainly creating something new within pop music, this wasn’t so much a case of pop music finally elevating itself to the level of art, as it was the noise it was making became so deafening that it was no longer possible to ignore it. Pop, it seemed, was here to stay. And, if you can’t beat them…

Art pop

Over the next two or three years, pop embraced art like never before. Let’s not forget that so many of the greatest pop acts come from art-college roots, from The Beatles to The Rolling Stones, The Who, David Bowie, Queen, REM, Blur, Pulp, Lady Gaga, and too many more to mention. And so the battle lines were being drawn. For pop’s elite in the mid-60s, you were either with them or against them. Fans of Bob Dylan, the darling of intellectual students who loved his political and protest songs, were shocked by what they saw as his “selling out” when he switched from acoustic to electric guitar. One disgruntled fan, Keith Butler, famously shouted “Judas” at him during a show at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in May 1966. Dylan replied contemptuously, “I don’t believe you.” When Butler was interviewed after the show, he sneered: “Any bloody pop group can do this rubbish!” The implication was that fans had come to see something of artistic merit – not pop music. But the times they were a-changin’.

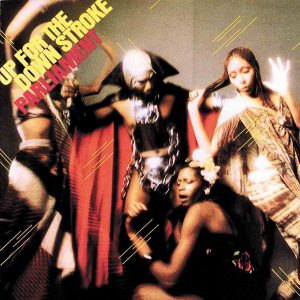

The pop album itself was by now becoming a recognized art form, and groups were thinking about every aspect of their work, with the album cover being elevated from mere pretty packaging to pop-art itself. Groups and singers would hire the best photographers and graphic designers to create their record sleeves, and work alongside filmmakers to produce artful promo clips. Perhaps the most obvious example of this embracing of the art world is Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, for whose cover The Beatles recruited the respected pop artist Peter Blake, but it’s worth noting that the idea for their “White Album” cover came out of conversations between McCartney and another respected pop artist, Richard Hamilton, who produced the poster inserted into the finished package.

Finally, pop had convinced the art world that the two camps were of a similar mind – pop was one of them. And yet it was in this very acceptance that a strange thing happened. With the launch of Rolling Stone magazine in 1967 came the beginning of serious pop criticism. Except it wasn’t called that; it was called rock criticism. Pop –short for “popular,” let’s remember – music was a catch-all term that became used to encompass whatever current styles were in vogue, be they the doo-wop of Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers, the rock’n’roll of Elvis Presley and Little Richard, the Merseybeat of Billy J Kramer & The Dakotas or The Searchers, or heartthrobs such as Ritchie Valens or Dion DiMucci. But now rock (without the roll) music was breaking away, distancing itself from pop as though in some way suggesting itself to be of a higher form. By 1968, you were either rock (alongside The Rolling Stones, The Doors, Pink Floyd, and Jimi Hendrix) or pop (like Cliff Richard, Lulu or Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich). Rock had its music press, its critics and its intellectuals; pop was now strictly for little kids and squares. In the very instant that pop finally became accepted as the art that it was, a coup from within saw it banished to the bubblegum shelf.

Snobbery exists around any form of art, and pop would be no different in this respect. While the critics (not to mention many fans and even the artists themselves) sought to draw a line between the artistically credible (rock) and the commercial (pop), other artists refused to be pigeonholed. The reality is, as with all art, that there is good and bad pop music. What proved difficult in the late 60s – and remains tough today – is to explain exactly what makes something good and something else bad. Marc Bolan is a good example of an artist that crossed the divide between rock and pop. His original Tyrannosaurus Rex were an interesting group, certainly closer to the outsider edges of rock than commercial pop, with plenty to attract critics while also appealing to hippies and art students. But when Bolan followed Dylan’s lead and ditched his acoustic guitar in favor of an electric one, shortened the band’s name to T.Rex, and ended his partnership with Steve Peregrin Took, the result was a run of pop singles that brought him greater popularity than any British artist had known since the days of Beatlemania. Indeed, a new term was coined to describe the mania: T.Rextacy. It was clearly pop, very definitely art, and, crucially, extremely good.

Taking pop music to a new level

Sweden’s Eurovision winners ABBA are another interesting case study. Surely nothing in the pop world could be further from art than this annual Europe-wide songwriting competition? Added to this, ABBA’s records sold by the bucketload. That people who wouldn’t normally pay any mind to the pop charts were falling in love with their well-crafted slices of pop should have removed any chance of credibility for the Swedish fab four. And, at the time, that may well have been true. But today, they are lauded for taking pop music to a new level.

Through the 70s, accusations of snobbery were voiced by many young pop fans – notably towards the increasingly cerebral noodlings coming from the prog rock camp. In 1976, these shouts became a roar, as punk rock exploded onto the scene. Punks were determined to reclaim pop music for the masses, refusing to see it disappear up its own rear end in a flurry of intellectualized virtuosity. Pop was for everyone, regardless of talent. In a way that harked back to the skiffle groups that had sprung up all over the country in the late 1950s, leading to a wave of bands from The Beatles and the Stones, to The Animals, Kinks, and countless more, punk was about a look, an attitude, and expression, far more than it was about being able to play guitar. And both scenes took seed in Britain’s art schools.

Image is the key to success

Key to pop’s success has always been image. From Sinatra’s blue-eyed good looks through the dangerous sex appeal of Elvis to David Bowie’s androgynous attraction, how an artist presents him or herself is part of the package. While the music is clearly key, the visual effect is a huge part of pop – another tick in the Yes column in the old “is pop art?” debate. The art world embraced this notion with the pop art movement, but these artists could never present the full pop package in a gallery, however good their work was. As Pete Townsend of The Who explained to the Melody Maker in 1965, pop art was: “I bang my guitar on my speaker because of the visual effect. It is very artistic. One gets a tremendous sound, and the effect is great.”

The post-punk pop world embraced this same idea in the early 80s. Pop groups became more flamboyant than ever before, with each act presenting itself in its own distinct fashion. Whether this be Boy George’s at-the-time shocking appearance in make-up and dresses, Adam Ant with his mini-movie pop videos and characters, or Martin Fry from ABC, wearing a gold lamé suit as he emerged from the dole in Sheffield. New romantics and new wave acts such as The Human League, Soft Cell, and Duran Duran exploited the value of image to enhance their music, creating a richly diverse pop scene that would sustain them for decades to come.

Meanwhile, American stars were similarly controlling every aspect of their presentation to ensure they were in control of their art. Michael Jackson’s videos became big-budget epics, rivaling Hollywood for their extravagance, while Madonna’s sexually charged performance elevated her stage shows to grand theatre.

This was the blueprint followed by Lady Gaga, who became an international superstar following her 2008 debut album, The Fame. A former student at New York’s Tisch School Of The Arts, Gaga fused her avant-garde electronic music with pop sensitivities, added a splash of Bowie/Bolan glam, and presented herself as a complete package of music backed up by flamboyant and provocative visuals. As she explained, “I am a walking piece of art every day, with my dreams and my ambitions forward at all times in an effort to inspire my fans to lead their life in that way.”

Whatever you call it, the music remains the same

Over the decades, the definition of pop has changed too many times to mention. In times of rude health, everyone wants to be associated with it, while in fallow times, artists have made great efforts to distance themselves from it. As we know, pop simply means “popular,” but it can also mean a style of popular music. The word is often used to describe music that has mass appeal, produced with a big budget, and intended to be commercially successful. And it’s this commercial success that alienates many who feel this aspect of the music business sets itself aside from the purists who consider their music to be art for its own sake. Rock fans would distance themselves from what they saw as disposable pop in the 80s, and yet the groups they loved used many of the same tools as their perceived enemies – image, flamboyance, and so on.

What exactly pop is will be different from one person to the next. Many people think of Motown as soul, but to the soul purist, Motown is pop, not soul. They view Motown as somehow inferior, due to the business-like nature of head-honcho Berry Gordy, producing a conveyor belt of hits. However, by the early 70s, Motown artists such as Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye were firmly in charge of their own output, with albums like Gaye’s What’s Going On and Wonder’s Music Of My Mind as soulful as anything coming out of Memphis or Muscle Shoals. But at the same time, they remain some of the greatest pop records ever made.

When the great soul label Stax Records, home to Isaac Hayes, The Staple Singers and the late Otis Redding, invited the Reverend Jesse Jackson to open “the black Woodstock,” as their Wattstax festival was dubbed, he preached inclusiveness: “This is a beautiful day, it is a new day. We are together, we are unified and all in accord, because together we got power.” He continued, using music as a metaphor: “Today on this programme you will hear gospel, and rhythm and blues, and jazz. All those are just labels. We know that music is music.”

Whatever you call it, the music remains the same. The discussion is only about how we interpret it – and what it says about us. Do those who dismiss pop as having no value really just suffer from the snobbery of wanting others to think that they, like the playwright in Stoppard’s play, are above such childish things as pop music?

As Henry laments in The Real Thing, “I’m going to look a total prick, aren’t I, announcing that while I was telling the French existentialists where they had got it wrong, I was spending the whole time listening to The Crystals singing ‘Da Doo Ron Ron.’”