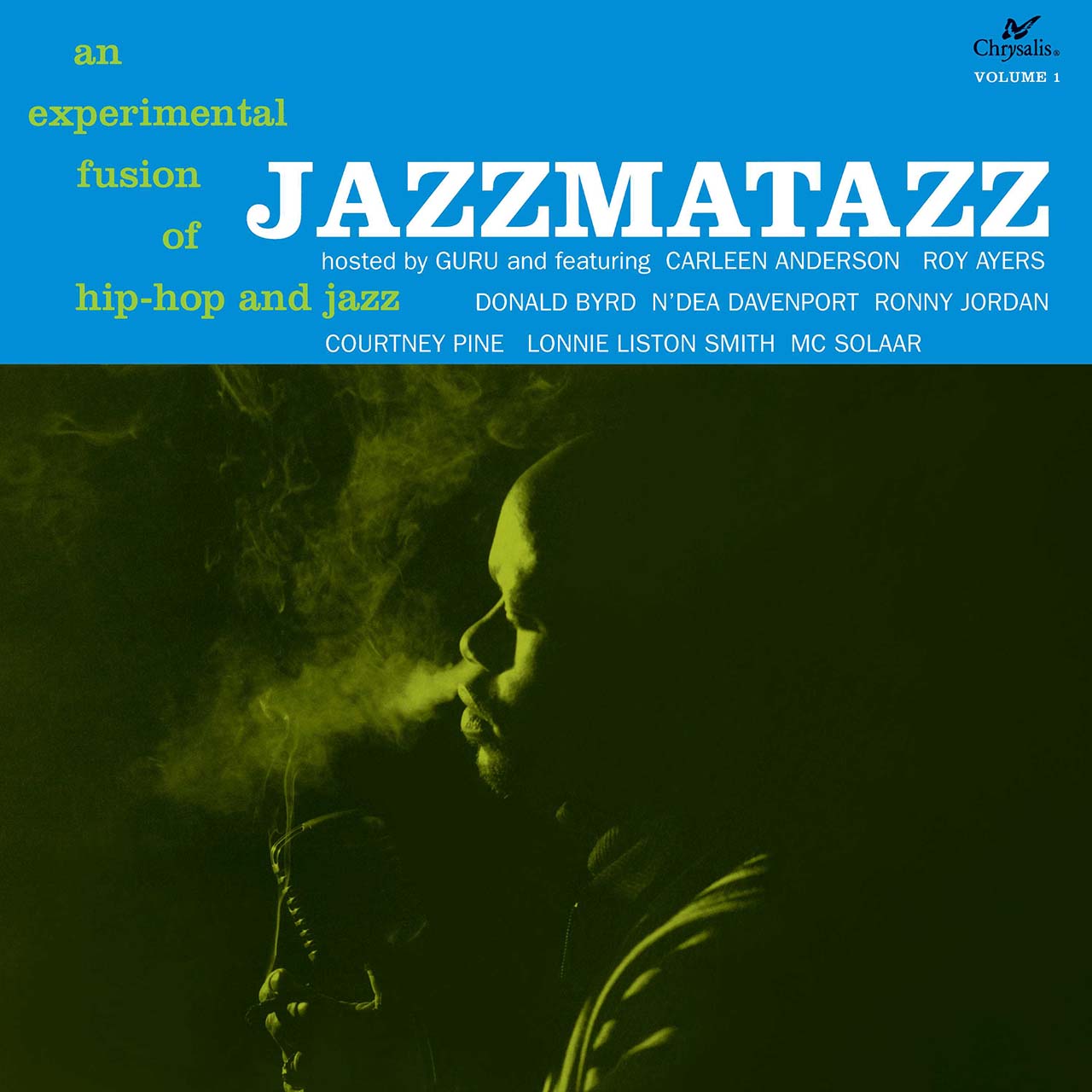

“Peace, yo, and welcome to Jazzmatazz, an experimental fusion of hip-hop and live jazz,” announces Guru in his trademark suave monotone at the outset of the MC’s 1993 solo album. At the time, a wave of hip-hop artists headed up by A Tribe Called Quest, Digable Planets, and Guru’s own group Gang Starr (alongside producer DJ Premier) were receiving critical acclaim for unearthing and flipping jazz samples into their hip-hop tracks. In Guru’s mind, the next logical step was to formalize the arrangement by reaching out to original artists whose music they’d been sampling – Roy Ayers, Donald Byrd, and Lonnie Liston Smith – and getting together in the studio.

Listen to Guru’s Jazzmatazz Volume 1 now.

Anchored by smooth, rolling boom-bap drums, Jazzmatazz spotlights a roster of sax giants, trumpet maestros, and piano players who bought into Guru’s concept by providing sample-worthy riffs that become the melodic thrust of the album’s 12 tracks. (In most cases, the musicians are also granted a few extended bars at the end of each outing to stretch out, improvise, and showcase their chops.) Early on, saxophonist Branford Marsalis infuses Guru’s “Transit Ride” guide to navigating the New York City subway system with a fittingly taut quality; the singers N’Dea Davenport and Dee C. Lee bring an acid jazz sheen to “When You’re Near” and “No Time To Play” respectively (with the latter featuring vibes work from Roy Ayers); and Lonnie Liston Smith’s piano lines add the lonesome aura of the blues to “Down The Backstreets.”

A convincing harmony emerges between Guru and the various musicians, aided by the MC’s brilliantly economical flow. Whether laying down compact braggadocio bars or short cautionary character-based vignettes, the always unruffled Guru lets his voice become part of the track’s mood. “Many legacies of brothers who get busy/ And I do it fluid ’til the suckers get dizzy,” raps Guru on “Loungin’,” backed by Donald Byrd’s overlapping trumpet lines. Nodding to the feeling of mutual respect that permeates Jazzmatazz, Guru shouts out “peace to the pioneers” and celebrates Byrd and himself as “the horn player and the dope rhymesayer/ Quite emotional and inspirational.”

Released in 1993, Jazzmatazz made plain the potential of jazz-rap. Adding weight to the idea, later that year the UK group US3 were granted carte blanche to sample selections from the iconic jazz label Blue Note’s deep vaults. (Blue Note also repackaged its most sampled wares into the Blue Break Beats compilation series, complete with liner notes documenting precisely which hip-hop producers had repurposed the dusty grooves.) But hip-hop moves at light speed. By the time of Jazzmatazz‘s release, Dr. Dre was moving hip-hop toward a sleek G-funk zone with The Chronic and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s Doggystyle, while RZA and the Wu-Tang Clan striped New York City hip-hop down to a fantastically grungy essence. Likewise, Gang Starr’s own upcoming release, 1994’s Hard to Earn, replaced the smoky jazz samples of 1992’s Daily Operation with an emphasis on weighty crunching drums and more angular and abstract chopped samples. These developments conspired to take some shine away from Guru’s experiment, but three decades later, Jazzmatazz endures as a highly listenable timepiece that nods warmly to an era when modern rap cats and veteran jazz figures broke bread and became musical kinfolk.