By the time Joe Henderson arrived at Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey recording facility in April 1964 to record his third Blue Note album, In ‘N Out, the 27-year-old saxophonist – who only twelve months earlier had made his debut as a sideman on trumpeter Kenny Dorham’s Una Mas LP – was known as an accomplished studio musician. The numerous sessions he logged during his first year with the iconic Big Apple jazz label – ranging from Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder to Andrew Hill’s Point Of Departure – showed him to be equally at home with hard bop and more exploratory jazz, and made him a valuable asset for Blue Note producer Alfred Lion.

Henderson had been brought to Lion’s attention by Dorham, who played on and contributed material to the saxophonist’s previous Blue Note albums, Page One and Our Thing. He became friends when Henderson, thirteen years the trumpeter’s junior, arrived in New York in 1962. The older musician soon became Henderson’s trusted mentor and close collaborator. And, as In ‘N Out’s outstandingly blended horn arrangements reveal, the two musicians developed a deep musical rapport. “We have some kind of vibration going,” Henderson explained in 1963. “Even when we play unison lines, it seems we breathe at the same time.”

Listen to Joe Henderson’s In ‘N Out now.

Joining Dorham alongside Henderson on In ‘N Out were two highly regarded members of the John Coltrane Quartet, pianist McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones, who injected the session with a pulsating synergy. Gluing the rhythm section together was the imaginative double bassist Richard Davis, who – three weeks before – had played with Henderson and Dorham on Andrew Hill’s avant-garde masterpiece, Point Of Departure.

Driven by a frantic, high-octane intensity, the album’s title track is a progressive hard-bop piece teetering on the brink of avant-garde music. The Henderson-penned number stands as a forceful declaration of intent, encapsulating the saxophonist’s skill at being able to play both “inside” and “outside” of what jazz musicians call “the changes”: in jazz-speak, “Inside” refers to operating within a conventional jazz framework, while “Outside” is the ability to stretch beyond the accepted parameters of melody, harmony, and form.

While “In ‘N Out” pushed hard bop to breaking point, in striking contrast, the infectiously melodic “Punjab” pulls back from the precipice of free jazz. It offers a release from tension, as does the aptly titled “Serenity,” a sweetly swinging groove that eventually became a jazz standard.

The Latin-flavored “Short Story” is the first of two Dorham-penned numbers; the second one, the swinging closer “Brown’s Town,” is notable because it’s the only track where Henderson isn’t a featured soloist.

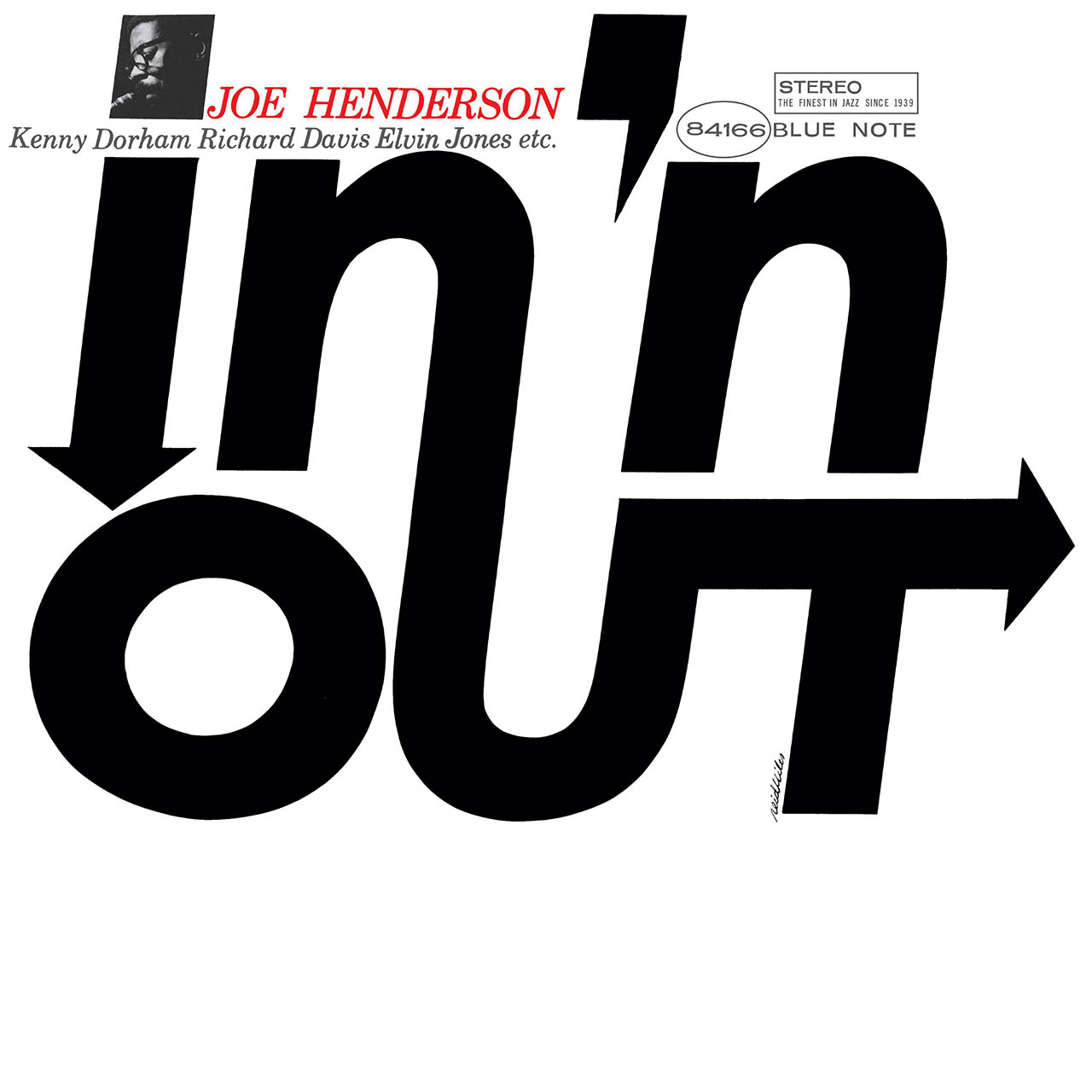

Jacketed in an archetypal Blue Note front cover with bold, eye-catching typography designed by Reid Miles, In ‘N Out landed in record stores in early 1965. By then, Henderson was working in pianist Horace Silver’s band – it was his memorable solo that lit up Silver’s classic hit tune “Song For My Father” – but he would stay at Blue Note as a solo artist, recording two more albums for the label (Inner Urge and Mode For Joe) before leaving in 1967.

Showing Henderson’s growing maturity as a composer and a saxophone player, In ‘N Out affirmed Kenny Dorham’s assertion that “Joe is full of ideas and he avoids cliches.” Though schooled in the ways of bebop – Charlie Parker was his primary influence – Henderson strove to push beyond the music’s limits into unchartered territory. By turns strident and lyrical, In ‘N Out skilfully navigated a tightrope between the jazz tradition and more progressive music. It was a quality that marked him as one of the foremost tenor saxophonists of the 1960s.