Married life has been portrayed as harrowing for women in Korean society for a while. In highbrow media, award-winning literature like Kim Ji-young, Born In 1982 by Cho Nam-ju and The Vegetarian by Han Kang show women whose suffering is magnified by marital demands. In popular culture, the emotional turmoil and fallout of infidelity and spousal neglect are common themes of melodramas like The World of the Married and On the Way to the Airport. These works draw inspiration from the real world to comment on serious social issues. Marry My Husband touches on many of these issues affecting Korean women and attempts to resolve some of the anxieties about patriarchal violence with magic and wish fulfillment. The TVN 16-episode drama has been adapted from novel, to webtoon, and makes an entertaining entry into the reincarnation revenge rom com genre, a style of storytelling familiar to the very online or lovers of the 1998 film Sliding Doors.

*This review contains minor spoilers for Marry My Husband.

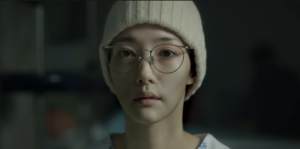

Starring the icon of the office romcom, Park Min-young, Marry My Husband’s plot is complicated to explain but easy to follow: Kang Ji-won has been mistreated by her abusive, cheating husband Park Min-hwan and her duplicitous best friend Jeong Sung-min for most of her pubescent and adult life. Ji-won meets a violent death when she discovers Sung-min and Ji-won are having an affair. But she is reincarnated ten years earlier with the opportunity to avoid her fate but only if someone else takes it.

The show dedicates time to the mechanics of the universe to emphasise Jiwon’s perspective and portray abuses endured by heterosexual young women at work and in intimate and family relationships. Marry My Husband takes a specific lens to gendered society and tries to solve social ills with romantic love and girlboss feminism.

“Now marriage can be a source of joy and love and mutual support but why do we teach girls to aspire to marriage and we don’t teach boys the same? We raise girls to see each other as competitors not for jobs or accomplishments, which I think can be a good thing, but for the attention of men.” ― Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, We Should All Be Feminists

Women in South Korea have made a strong declaration against social conventions in the last decade. The Escape the Corset and 4B Movement were popularised by feminists refusing the conventional trappings of success, typically sharing their stories on social media. Heterosexual relationships, marriage, and childbirth are refused as the ultimate prize of a well-lived life. The common struggles of women in the workplace like sexual harassment and unfair abuses of power have also been named as reasons for women’s disillusionment with tradition. People have reactively created communities and adult care networks based on free association and friendship. Subversive strategies of protest against restrictions to unconventional partnerships have gained support like the woman who adopted her best friend. These movements have art and media promising personal autonomy without loneliness, exploitation, and fear of violence if they are embraced. Marry My Husband acknowledges many of the struggles of these women but suggests romantic ideals can still be reached with the cooperation of sympathetic men and capitalist success.

The symbolic cutting of Ji-won’s hair during her makeover before confronting her high school bullies could be thought of as a nod to the Escape the Corset movement. Short hair is viewed as a visible marker of divestment from strict feminine beauty standards. But this is integrated into a shopping and makeup montage, showing she is still using the standards of beauty but refusing its most conservative presentation.

Marry My Husband is a fascinating watch because its problems are realistic but the solutions are fanciful. The episodes take on an allegorical structure to model different problem solving strategies, always encouraging the parable’s heroine to try her best to live according to clear moral tenets. The principles themselves are iffy when it comes to measurable gains for women’s rights and instead shows Park Min-young in many luxurious dress-up montages. It is a comforting fiction that a makeover and assertiveness skills are the key to a successful life. Trying your best isn’t always enough but the drama insists this is better than another alternative.

“I’m the type to run away when things get too hard, but you should try all you can before that. I need to know if these people are simply crazy or have good reasons so I don’t have regrets later,” – Yu Hui-yeon

The actors’ performances of these different versions of the perilla leaf debate is one of the highlights of the drama. Song Ha-yoon’s portrayal of the materialistic and perversely passive aggressive, false friend Sung-min is one for the ages. Her character’s complexity does not diminish from the criticism that it bears a resemblance to sexist stereotypes of shallow women who use their “feminine wiles” to get ahead. Girls’ girls can only escape these accusations by using their materialistic powers for good. Yu Hui-yeon, played by Choi Gyu-rui, is the authentic, rich, bubbly, and confident best friend that Ji-won deserves. And being the sister of the romantic lead means she’s unlikely to commit adultery with him.

The drama sorts people and relationships into fake and authentic versions and then illustrates the quality of “real” vs “copy” friends, marriages, men, and women across the episodes. Real men can be ghosts like Ji-won’s magical father but they are characterised by their honesty, desire to protect and support women. “Real” office romances are consummated after working hours and not during out-of-office promotional events. But many of the wish fulfillment fantasies are also inappropriate and are only variations of established problematic courtship patterns.

The show’s minimising of the red flags in the main couple’s love story sometimes rings a sour note. Na In-woo does his best to give Yoo Ji-hyeok an awkward innocence to explain away his stalking and abuses of power as attempts to protect Ji-won. His character’s growth and eventual triumph is significant but not convincing as the representative for Good Guys everywhere. Ji-won’s journey to independence and self-esteem is more exciting when Ji-hyeok is helping her defeat her enemies than when they are falling in love. The story loses steam when trying to find realistic explanations for his motivations and reassurances that he is trustworthy. The solution to the problem of his benevolent patriarchy is that he is a mystical gift from Ji-won’s benevolent patriarchal ghost dad and so they are meant to be.

Marry My Husband uses clever and layered storytelling to try to revitalise old fictions. It is through the cooperation of good people, who outnumber and have more power than bad people, that the corrupt and abusive are exposed and rooted out of society. In the drama, once the evil abusers of the system have been brought to justice, everyone gets their happy ending. The happy ending is still achieved at someone’s expense and the problems introduced to expose common social realities are inelegantly shoved out of frame.

This perspective doesn’t allow for the kinds of radical reforms suggested by 4B and other feminists. There’s no space in this world for LGBTQIA+ and chosen family structures. The lines between co-worker and family member are blurred but no one is allowed to remain single by the last episode. Some dramas like Don’t Dare to Dream that features a storyline with an asexual, aromantic man, allow for single and queer people to exist in their world but this is not one of them.

Marry My Husband makes the case that it is not gendered expectations that are problematic but the strictness and manner in which they are applied. A partner attracted and maintained with tactics like deception, cheating, and manipulation requires punishment in a just system.

The drama’s rhetoric is seductive to a certain mood. The entertainment of watching villains receive their comeuppance by luck or design is only slightly diminished by its tunnel vision to a certain kind of happiness. The drama is full of humorous “what if” scenarios that are as much related to real life as a tradwife TikTok account. It markets pollyannaish attitudes to gender-based violence while acknowledging that they are unrealistic. It has many good qualities but where it falls short is imagination: a progressive future with single, queer, and unconventional people can still exist in a world of love.

(The Conversation, The Dial, Herald Insight, Stats Korea (1), Applied Economics, OECD Library, NPR, Images via TvN)