Many records are ephemeral – a collection of songs to make us dance, smile or cry – but sometimes you truly bond with a special album, one where you are moved by the triumph of ambition and vision of the musician or band who made it. One of the earliest examples of this high-minded, epic music – and perhaps one of the greatest albums in the history of music – is John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme.

In 1959, Coltrane had played on Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue, a benchmark of improvisation that, in the trumpeter’s words, “distilled modern jazz into a cool and detached essence,” so he knew how high the bar was for true excellence. Five years later, in the most meticulously planned recording of his career, Coltrane recorded his own masterpiece.

A work of art

At the time, Coltrane was raising children with his second wife, Alice, a harpist and pianist, in the suburbs of Long Island. The pair shared an interest in spiritual philosophy and Alice recalled the summer day when Coltrane descended the stairs “like Moses coming down from the mountain,” holding a complex outline for a new work. “This is the first time I have everything ready,” he told his wife. The four suites of what would become A Love Supreme were called “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance” and “Psalm.”

A Love Supreme was originally arranged for an ensemble of nine musicians, but when it came to the recording session in New Jersey – completed in one day, on December 9, 1964 – Coltrane used his classic quartet: McCoy Tyner on piano; Jimmy Garrison on bass; Elvin Jones on drums; Coltrane himself on tenor saxophone. For the first time, Coltrane was also credited with vocals (he chants at the end of the first suite). Archie Shepp, who played tenor saxophone on alternate takes of “Acknowledgement,” said: “I see it as a powerful, spiritual work… a personal commitment to a supreme being.”

The epic music was a high-water mark in Coltrane’s career and boosted his popularity, generating two Grammy nominations and topping a series of critics’ polls in 1965. This musical declaration of a spiritual quest, launched in the volatile atmosphere of the aftermath of Malcolm X’s assassination, was instantly hailed as work of genius. In his five-star review for Down Beat magazine, Don DeMichael said the album radiated a sense of peace that “induces reflection in the listener.” He called A Love Supreme “a work of art.”

The album’s influence has extended into the modern day. Jazz saxophonist Courtney Pine says that A Love Supreme is the album he has listened to most in his life, while Coltrane’s tour de force is referenced by U2 in their song “Angel Of Harlem.”

Freedom and abandon

Of course, Coltrane is far from alone in the jazz world in having made a definitive mark on the wider world of music, whether that is works by titans such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie; or with Thelonious Monk’s ability to translate emotions into the language of music. The freedom and abandon that Monk and his fellow star musicians – such as Sonny Rollins and Max Roach – achieve on the 1960 album Brilliant Corners also makes that an historic recording.

By virtue of simple chronology, jazz was also ahead of pop and rock music in terms of “concept” albums by artists displaying their own musical grand plan. Sometimes it was just about sheer innovation – as when Jimmy Smith created a blues-plus-bebop blueprint for the jazz organ with his groundbreaking 1956 album A New Sound, A New Star. Some musicians ventured into new territory, such as the marriage of melody and Latin in Getz/Gilberto by Stan Getz and Brazilian guitarist João Gilberto.

Others went for artistic homage, such as Under Milk Wood, Stan Tracey’s evocative 1965 collection of themes inspired by the Dylan Thomas radio play of the 50s, or personal exploration, as in Horace Silver’s Song For My Father, with its momentous title track inspired by a trip that the musician had made to Brazil; or Miles Davis’ Grammy-winning Sketches Of Spain. This sense of artistic boldness and epic music has continued into the present era with musicians such as Herbie Hancock, who, in his seventies, is still one of the great experimenters in the field of jazz.

The era of the epic album

As rock, folk, and country music grew in popularity so did the ambitions of its best practitioners to make impressive albums. In the mid-60s, after the artistic and commercial success of Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home, musicians began to respond to and compete with each other to make epic music. With Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys’ symphonic Pet Sounds, “pop” had entered the era of the album. By the late 60s, rock musicians who wanted to be thought of as bold, innovative, and artistic were concentrating on long-playing records, at a time when the singles market was hitting a plateau.

Just after the watershed year of 1967 – when stunning albums by The Beatles (Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band) and Jefferson Airplane (Surrealistic Pillow) were released – more and more bands jumped on the album bandwagon, realizing that the format gave them the space and time to create different and challenging sounds. The days of record labels wanting a constant production line of three-minute singles were disappearing. By 1968, singles were being outsold by albums for the first time, helped by the increase in production quality of high-fidelity stereo sound and the idea of the album as an artistic whole. The time spent making long-players changed from hours to weeks, or even months.

This also came at a time when journalism began to give rock music more considered attention. In February 1966, a student called Paul Williams launched the magazine Crawdaddy!, devoted to rock’n’roll music criticism. The masthead boasted that it was “the first magazine to take rock and roll seriously.” The following year, Rolling Stone was launched.

The birth of FM radio

Another important turning point in the rise of the album had been a mid-60s edict from the Federal Communications Commission, which ruled that jointly owned AM and FM stations had to present different programming. Suddenly, the FM band opened up to rock records, aimed at listeners who were likely to be more mature than AM listeners. Some stations – including WOR-FM in New York – began allowing DJs to play long excerpts of albums. Stations across America were soon doing the same, and within a decade FM had overtaken AM in listenership in the US. It was also during this period that AOR (album-oriented radio) grew in popularity, with playlists built on rock albums.

This suited the rise of the concept album by serious progressive-rock musicians. Prog rock fans were mainly male and many felt that they were effectively aficionados of a new type of epic music, made by pioneers and artisans. The prog musicians believed they were trailblazers – in a time when rock music was evolving and improving. Carl Palmer, the drummer for Emerson, Lake & Palmer, said they were making “music that had more quality,” while Jon Anderson of Yes thought that the changing times marked the progression of rock into a “higher art form.” Perhaps this was the ultimate manifestation of “pop” becoming “rock.”

The avant-garde explosion

Lyrics in many 70s albums were more ambitious than the pop songs of the 50s and 60s. Similes, metaphors, and allegory began to spring up, with Emerson, Lake & Palmer emboldened to use the allegory of a “weaponized armadillo” in one track. Rock bands, sparked perhaps by Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, seemed to be matching the avant-garde explosion in the bebop era: there was a belief in making albums more unified in theme but more disparate in sound.

In a June 2017 issue of The New Yorker, Kelefa Sanneh summed up the persistent popularity of this new genre by saying, “The prog-rock pioneers embraced extravagance: odd instruments and fantastical lyrics, complex compositions and abstruse concept albums, flashy solos and flashier live shows. Concert-goers could savor a new electronic keyboard called a Mellotron, a singer dressed as a bat-like alien commander, an allusion to a John Keats poem, and a philosophical allegory about humankind’s demise – all in a single song (“Watcher Of The Skies”) by Genesis.”

Genesis were one of the bands leading the way in terms of epic music. One song, which comes in at just under 23 minutes, is the marvelous “Supper’s Ready.” which Peter Gabriel summed up as “a personal journey which ends up walking through scenes from Revelation in The Bible… I’ll leave it at that.”

Another way of creating an epic feel for rock bands was to use an orchestra. This had been done before by jazz musicians. Duke Ellington’s “Jazz Symphony,” composed in 1943 for his first Carnegie Hall concert, was one of his most ambitious works, while an orchestral sound was used to great effect in the seminal Verve album of 1955, Charlie Parker With Strings.

One modern-day exponent of blending jazz and classical is Chick Corea, who brought this to fruition in 1996’s The Mozart Sessions, an album made with Bobby McFerrin and the St Paul Chamber Orchestra. Corea, a former Miles Davis sideman, has always sought to make high-minded and ambitious albums, something he achieved again with his 2013 Concord outing recorded Trilogy, a three-disc live album that has been described as “a dizzying musical autobiography.”

Where Charlie Parker went, rock musicians followed. The worlds of rock and classical music coming together is now common, but in the 60s it was a groundbreaking move. The Moody Blues led the way with 1967’s Days Of Future Passed, an album that featured Peter Knight conducting The London Festival Orchestra. At the heart of that fine record is the stunning song “Nights In White Satin.” Deep Purple’s Concerto For Group And Orchestra is another defining moment, with Jon Lord masterminding the collaboration between the rock band and The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

In his pick of 25 classic orchestra rock tracks for uDiscover, Richard Havers says, “Other prog practitioners that have used an orchestra to great effect are Yes, on their cover of Richie Havens’ ‘No Opportunity Necessary, No Experience Needed’ that quotes the theme to the film The Big Country, written by Jerome Moross. Later, Yes didn’t need an orchestra as Rick Wakeman joined and, with a battery of keyboards, he did the same job. However, for his solo album Journey To The Centre Of The Earth, Rick used The London Symphony Orchestra.”

Read it in books

Sometimes, however, just a single track created major shockwaves, as with Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale” or The Doors’ “Light My Fire.” Led Zeppelin IV, recorded over three months in London at the end of 1970, contains some splendid songs, but few more celebrated than the imperious “Stairway To Heaven,” written by Jimmy Page and Robert Plant.

Sometimes a philosophical theme sparks a creative urge. Scores of musicians have used the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in their epic music. The ancient Greek myth has inspired countless books, plays, poems, operas and ballets – as well as individual songs – but also a number of diverse albums, including a rock opera by Russian composer Alexander Zhurbin, and Metamorpheus, an instrumental album by former Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett. Perhaps most intriguing is the superbly offbeat album Hadestown, by country musician Anaïs Mitchell, which transports the myth to post-Depression-era New Orleans.

Literary inspiration has led to some fine “high art” albums. Among the successes have been Billy Idol’s Cyberpunk (inspired by William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer); Bruce Springsteen’s The Ghost Of Tom Joad (loosely based on John Steinbeck’s illustrious novel The Grapes Of Wrath); Lou Reed’s The Raven (which is among a host of music inspired by Edgar Allan Poe, including Tales Of Mystery and Imagination, the debut album by The Alan Parsons Project); Rush’s 2112 (the credits contain a nod to “the genius of Ayn Rand”, while elements of the album have parallels in her novella Anthem; in turn, the entirety of 2112 was later turned into a graphic-novel-inspired lyric video); Camel’s The Snow Goose (inspired by Paul Gallico’s novella of the same name); Pink Floyd’s Animals (taking cues from George Orwell’s Animal Farm); and David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs, also inspired by Orwell.

Another iconic album from the 70s came from English band Caravan – who were part of the so-called Canterbury Scene in the English county of Kent – called In The Land Of Grey And Pink, which features a Tolkien-influenced painting and which is considered the band’s masterpiece offering.

History repeating

It is not only literature that can spur attempts at epic music. Historical events can also evoke ideas for an album. They can be little-known independent gems – such as the folk-opera Hangtown Dancehall (A Tale Of The California Gold Rush) by Eric Brace and Karl Straub – to works by leading bands such as Iron Maiden. Their 2003 epic, Dance Of Death, had a series of songs about deaths in historical settings, including the powerful track “Passchendaele.”

Rick Wakeman is among those who have argued convincingly that Woody Guthrie’s 1940 album, Dust Bowl Ballads, is the daddy of all concept albums, inspiring so much of what followed in popular music. And country music has its share of albums that are grand in scale and even social commentary. In 1964, Johnny Cash recorded Bitter Tears: Ballads Of The American Indian, whose stark and sparse songs were built around stories about the mistreatment of the Native American. Congress had just passed the Civil Rights Act, looking to improve the lives of African-Americans, and Cash hoped his songs could draw attention to a similar human rights issue.

The Man In Black also recorded America: A 200-Year Salute In Story And Song. Across 21 tracks, with a threaded theme of violence in his nation’s life, Cash deals with everything from the legend of Bigfoot, to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and carnage at the Alamo.

The “country opera”

However, country albums could have major artistic aspirations without a big social theme. Emmylou Harris called her 1985 album, The Ballad Of Sally Rose, a “country opera.” It was about the life of a singer whose lover and mentor (loosely based on Gram Parsons) is a wild, hard-drinking musician. The songs – featuring contributions from Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt – flow into one another, creating a feeling of almost continuous momentum. Cash and Harris, incidentally, both appear with The Band’s Levon Helm on a grandiose storytelling album about Jesse James.

Other grand country classics include Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger and Kenny Rogers And The First Edition’s 1968 double-album, The Ballad Of Calico, based entirely around the Californian town of Calico. Each band member contributed vocals to create different characters, such as Diabolical Bill and Dorsey, The Mail-Carrying Dog. Though not strictly country music, Eagles’ Hotel California, with recurrent themes of American excess and superficiality, also merits a mention.

Epic music in response to current events

Political concerns have played their part in creating some significant high-minded albums and songs, including epic music from musicians as diverse as Green Day, Nina Simone, and Kanye West. Joan Baez released an album in Spanish (Gracias A La Vida) for Chileans suffering under Augusto Pinochet. Gil Scott-Heron started out as a writer and his 1970 book of poems, Small Talk At 125th And Lenox, was later accompanied by percussion and sung by the former novelist. The Chicago-born activist made a string of significant albums in the 70s – among them Pieces Of A Man and Winter In America – which he said allowed him to portray the “360 degrees of the black experience in the USA.”

Another stimulus to imagination has been the use of alter egos, most famously with Sgt Pepper but also memorably with Bowie’s The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. Pink Floyd, whose Piper At The Gates Of Dawn would make any list of the greatest albums, excelled with The Wall and its tale of the socially isolated Pink. The double-album is recognized as one of the great concept albums of all time.

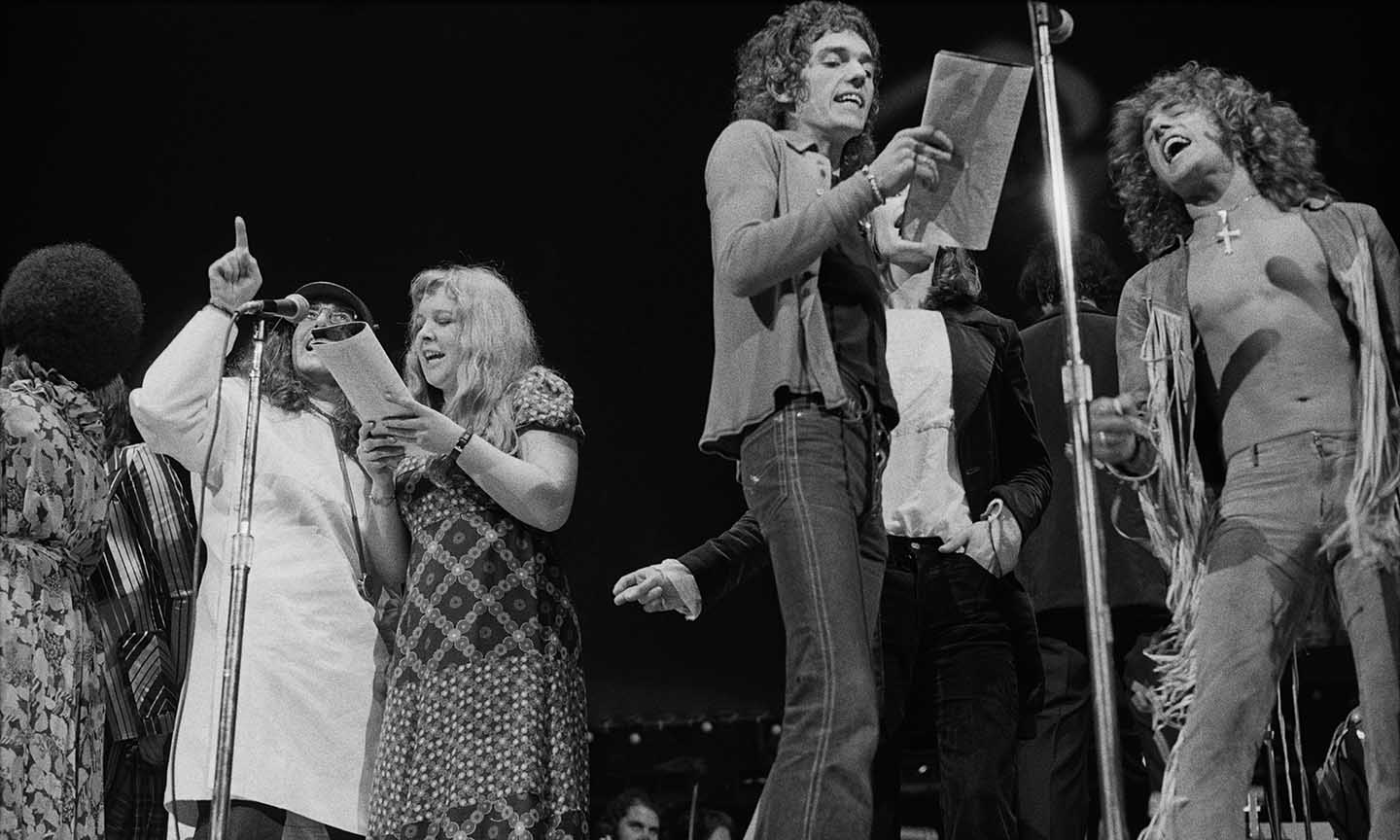

Into that category would come The Who’s Tommy, which was created at a time when Pete Townshend was studying Meher Baba, the Indian guru who had gone four decades without speaking. Townshend thought of his “rock opera” as a spiritual allegory of the “deaf, dumb and blind kid.” Its launch, in May 1969, was seen as an important cultural event.

Sometimes musicians pretended to take their “art” less seriously. Jethro Tull’s Thick As A Brick, featuring only one song, split into two half-album segments, was written as an ironic counter-concept album; strangely, the spoof ended up being considered one of the classic concept albums. Just as outlandish is Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake by Small Faces, where, on Side Two, the quirky story of “Happiness Stan” is recounted in a form of Spike Milligan-esque gibberish by Stanley Unwin.

Some of the very best albums create a state of mind and sensibility, such as the yearning nostalgia of The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society. The Kinks, who had previously recorded so many songs that were short, sharp satires, moved on to make ambitious albums that were unified by a central theme, such as Village Green and the even longer narrative follow-up, Arthur (Or The Decline And Fall Of The British Empire). The social commentary and pointed observation of an album about a disaffected young labourer were met with widespread acclaim.

When a musician has a successful and major back catalog, a minor masterpiece can occasionally be overlooked. Frank Sinatra’s 1970 album, Watertown, is a good example of this. The great crooner narrating the maudlin tale of a man abandoned by his wife, over the course of 11 tracks, is a brilliant, underrated album.

Born to be ambitious

With some musicians, it seems almost in-born to produce little other than complex, challenging, and epic music. Beck, Patti Smith, Richard Thompson (who was also the guitarist on Fairport Convention’s 1969 giant Liege And Leaf), Jackson Browne, Gretchen Peters, Elton John, Tim Hardin and David Ackles, whose American Gothic remains a classic, as does Lucinda Williams’ 1989 breakthrough, Car Wheels On A Gravel Road, would all fit into this category. So would the psychedelic vision of Grateful Dead or Jefferson Airplane’s best work.

The list could go on and on, of course, but it would be remiss not to mention Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, a timeless jazz-rock masterpiece featuring former Charlie Parker drummer Connie Kay. Morrison had been known primarily for singles such as “Brown Eyed Girl” before Astral Weeks, but this was a consciously-made entity, with the album’s two sides labelled “In The Beginning” and “Afterward.” It remains a triumph of music and imagination.

Another musician who has consistently aimed high in terms of artistic ambition is Tom Waits. For more than four decades, Waits has explored America’s low life – the booze, the drugs, the sleazy night-time characters – in a series of epic albums, including 1987’s Franks Wild Years, about a down-and-out called Frank O’Brien, and which was subtitled Un Operachi Romantico In Two Acts.

Some bands go on to influence the course of music that follows. Tangerine Dream produced albums that were impressionistic electronic extravaganzas. Edgar Froese, the leader who was inspired by avant-garde Hungarian composer György Sándor Ligeti, said that in creating albums such as Atem he was trying to “leave a little landmark of brave respect to others and to the dimensions of my own capability.” The landmarks were followed and Tangerine Dream were influential in inspiring a lot of New Age bands.

Epic music in the 21st Century

The quest to make epic music burns bright in the 21st Century. Max Richter’s groundbreaking concept album SLEEP, about the neuroscience of slumber, comes in at eight hours, 24 minutes and 21 seconds long. When it was performed at London’s Barbican in May 2017 it was done so as a “sleepover performance”, complete with beds.

Other modern bands creating substantial music would include Scottish band Mogwai; the electronic music of Aphex Twin (one of the recording aliases of Richard David James); and Texas rock band Explosions In The Sky, who have referred to their impressive albums as “cathartic mini-symphonies.”

A deserved addition to the list of musicians presently making epic concept albums is Steve Wilson, formerly the founder, guitarist and frontman of the Grammy-nominated progressive psychedelic group Porcupine Tree. Wilson’s forthcoming 2017 album, To The Bone’ (Caroline International Records) is highly anticipated, and its creator says, “To The Bone is, in many ways, inspired by the hugely ambitious progressive pop records that I loved in my youth: think Peter Gabriel’s So, Kate Bush’s Hounds Of Love, Talk Talk’s The Colour Of Spring and Tears For Fears’ Seeds Of Love.”

Talking about the scope of the album, Wilson added: “Lyrically, the album’s 11 tracks veer from the paranoid chaos of the current era in which truth can apparently be a flexible notion, observations of the everyday lives of refugees, terrorists and religious fundamentalists, and a welcome shot of some of the most joyous wide-eyed escapism I’ve created in my career so far. Something for all the family.”

Whether it’s joyous escapism, political anger, poetic lyricism or a personal spiritual quest that provides the fuel for a great album is not of prime importance. What matters, as Coltrane once said, is wanting “to speak to a listener’s soul.” Do that and you are likely to make your own contribution to epic music history.