1968 was a year of turmoil. Certainty was replaced by anxiety and old answers to vexed questions suddenly became hopelessly inadequate. Even the insular field of music faced profound change that year, and many record companies now faced an uncertain future in a fast-changing landscape. One such was Stax Records. In 1968, it was entirely possible – in fact highly likely – that this iconic soul label would not survive the year at all.

Stax’s biggest star had been killed in a plane crash in 1967. Lost alongside Otis Redding were linchpin members of The Bar-Kays, the band that played on numerous Stax classics as well as their own mighty records. In the wake of Redding’s death, Stax’s loyal staff, a unique mixture of black and white southerners who had seen the label soar from tiny Memphis hopefuls to major players, were surely wondering how they could recover from this awful blow. Surely things must get better in 1968?

Listen to Stax ’68: A Memphis Story on Apple Music and Spotify.

They didn’t know the half of it. In the wider world, the hippie dream of peace and love would be blown apart by a tumultuous year. The political scene soured in 1968. Memphis’ waste-collection services were crippled by a strike for more than two months, called when two black workers were crushed to death. During a related protest in the city on March 28, attended by civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, one of the protesters, Larry Payne, died after being shot by police. He was just 16.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King was ruthlessly slain at the Lorraine Motel, just two miles from Stax Records. The hotel was well-known to the label: it was where Steve Cropper of Booker T & The MGs, and singer Eddie Floyd had written his mega-hit “Knock On Wood.” Following Dr. King’s assassination, rioting erupted across American cities, including Memphis. President Lyndon B Johnson stepped up America’s involvement in the Vietnam War and more than half a million US fighting men were engaged there. US embassies were besieged by protesters across the world, and peace marches became bloody clashes with the authorities.

Stax could hardly ignore these seismic events, though until this point the label was not known for making outright political statements. Its political stance was more by example, perhaps: the music it issued was 95 percent soul, and the company was racially integrated in a way that was still rare in the South. But all the same, the feeling of the times came through in some of the label’s songs, such as Derek Martin’s “Soul Power,” Shirley Walton’s touching “Send Peace And Harmony Home,” and Dino & Doc’s “Mighty Cold Winter.” The latter, picked up from independent producer Bill Haney, was a tale of sadness that didn’t mention Vietnam but featured lyrics that anyone who’s lost their lover in that bleak conflict could appreciate.

An unbreakable resolve

Amid this growing societal tumult, Stax’s business model collapsed spectacularly. Stax had been distributed by Atlantic, which was sold to Warners in 1967. Stax assumed a deal could be done with Warners too, but no agreement could be reached. When Jim Stewart, Stax’s boss, asked for its master tapes back, Warners refused: Stewart had accidentally signed over all his previous material to Atlantic in a contract clause he hadn’t read. Stax was now a record company with no back catalog, no distributor (once the distribution deal expired in the spring of 1968), and would have to rely on income it could generate from new material. The company had also lost Sam & Dave, one of its biggest hit-making acts, because they were only “on loan” from Atlantic to Stax. In May 1968, a concerned Stewart sold Stax to Paramount, securing its future even if it had no past. Jeanne & The Darlings’ Stax B-side “What Will Later On Be Like” may have been about love troubles, but the uncertainty in its title could have applied to their record label.

However, one bright spot was clear: Stax retained the affection of its home city. While businesses around Stax’s Memphis HQ were wrecked by protesters in the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King’s death, the record company remained untouched. The fact that Stax did survive and deliver fresh music of unparalleled beauty, heart, and dignity is a testament to the power of soul and the unbreakable resolve of the people who made it.

Stax effectively had no catalog, so its creative core set about building one, with A&R Director/Vice President Al Bell setting out an ambitious plan to release 30 albums in a year (it was actually 27, still a remarkable achievement). These were supported by a huge number of singles, collected in full on the new 5CD box set Stax ’68: A Memphis Story. Necessity is the mother of invention: Stax Records’s 1968 single schedule is packed with magical music.

The start of Stax Records’s 1968 was overshadowed by the loss of its greatest star on December 10, 1967. On January 8, 1968, the label released “(Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay”, Otis Redding’s first posthumous hit, and the record that indicated he had seen how times were changing and would have been ready to change accordingly. The label also released tributes to the lost star, such as William Bell’s heartfelt “Tribute To A King,” originally a B-side but flipped by radio DJs; and “Big Bird,” Eddie Floyd’s explosive, semi-psychedelic lament written while he was waiting at an airport for a flight to take him to Memphis for Otis’ funeral.

The tip of the iceberg

Stax still had the kind of roster other soul labels would have killed for. Even its lesser lights were capable of cutting records of the highest order, such as Ollie & The Nightingales (“I Got A Sure Thing”), Mable John (“Able Mable”) and Linda Lyndell, whose “What A Man” is now regarded as one of the keystones of the catalog thanks to a profile-boosting 1993 interpretation by En Vogue and Salt-N-Pepa, though it was by no means the hottest single Stax Records issued in 1968. That honor goes to the million-selling “Who’s Making Love”, a sly and sassy tale of cheating which made a star of Johnnie Taylor after years of trying. But this was just the tip of the iceberg for Stax Records in 1968.

William Bell hit a purple patch that year, and his lovely ballad “I Forgot To Be Your Lover,” a Top 50 pop hit in the US, has proved one of soul’s most resilient and most-covered songs. His duet with Judy Clay, “Private Number,” enjoys similar status. Booker T & The MGs cut two hits in 1968: “Soul Limbo” (another tune with staying power as the theme for the BBC’s enduring Test Match Special in the UK) and the moody title music from the Clint Eastwood western Hang ’Em High. A last hurrah at Stax for Sam & Dave, “I Thank You,” went Top 10.

Rufus Thomas’ punchy “The Memphis Train” displayed funky energy of a sort described in Derek Martin’s “Soul Power,” but neither record was a hit. Stax also experimented with some contemporary pop acts who perhaps had something to say about their era, such as The Memphis Nomads, who cut “Don’t Pass Your Judgement,” and Kangaroos, whose “Groovy Day” was like a Northern soul version of The Young Rascals. But two African-American acts who took important steps at Stax Records in 1968 would become lasting stars who documented their times in very different ways.

Soul power

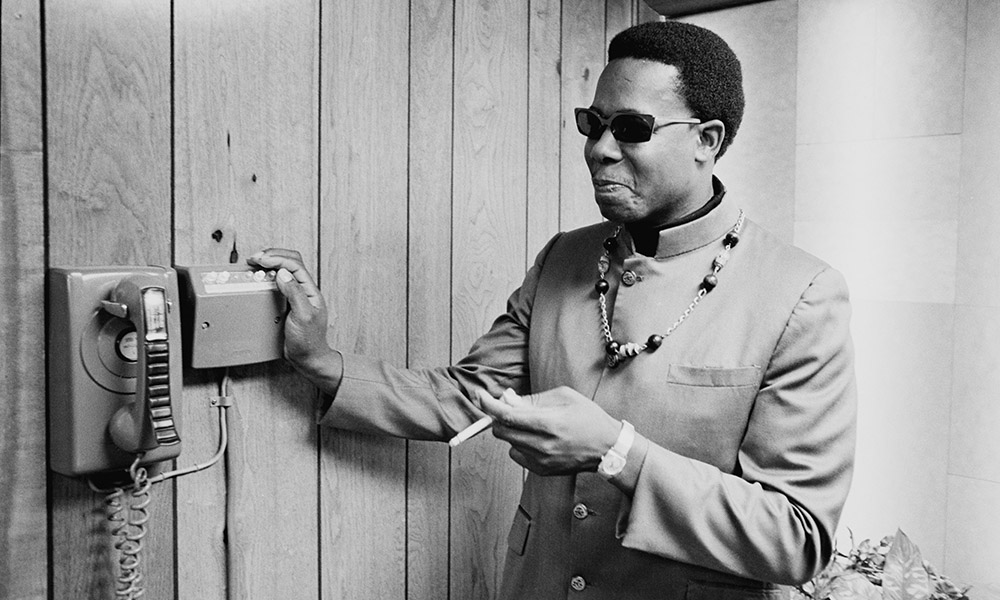

Isaac Hayes had been at Stax since the early 60s, composing heaps of hits alongside David Porter. A fine keyboardist, he’d worked on numerous sessions, but Hayes had never sought a solo career; though, in 1965, he’d released “Blue Groove,” a single on Stax’s Volt imprint, as Sir Issac & The Do-Dads, the label did not even spell his name correctly. 1968 saw the release of a further Hayes single, a jazzy jam called “Precious, Precious,” drawn from a mostly improvised album he’d taped the previous year. While this was never a commercial proposition, it did reveal Hayes’ unique baritone voice on record for the first time in three years. In 1969, that voice would become part of a symphonic revolution in soul.

Stax’s other voices for the future were new arrivals: The Staple Singers, a four-member family group, had started in gospel, shifted to folk, and were famed for their links with the civil-rights movement. While their work through the mid-60s grew increasingly pop-oriented, it took a shift to Stax to unleash their soul power. Their two opening salvos for the label, the singles “Long Walk To DC” and “The Ghetto,” found them singing better than ever and retaining their ability to cover serious topics. Stax Records wasn’t sure how to sell them at first, titling their 1968 debut album for the label Soul Folk In Action – an attempt to cover all bases. But within a couple of years, they’d receive far wider acceptance, taking their message music into the ghettos they sang about and to the pinnacle of the pop charts.

The Soul Children never matched the lasting success of the Staples, but their 1968 debut for the label was the R&B hit “Give ’Em Love.” For soul aficionados, they’d become one of the most revered of Stax’s post-68 acts.

By the end of the year, Stax had begun to rebuild itself. The label had distribution and signings who would take it into the 70s with a fresh, deeply soulful sound. 1968 was a pivotal year for everyone – and, like everyone else, Stax felt its way through it, somehow coping with every twist and turn.

1968 threw its worst at Stax Records, but the label refused to bring the curtain down. It had far too much soul power for that.

The 5CD box set Stax ’68: A Memphis Story is out now and can be bought here.