In the 1940s, New York City’s clubs overflowed with the sounds of cha cha, mambo, and rumba – and one label quickly seized on all of these music trends, helping to set the stage for salsa’s dominance in the mainstream years later. Tico Records was started by George Goldner, a garment manufacturer turned record impresario who began his career in music by running dance halls. At the time, the mambo craze was at its peak, and Goldner – an avid dancer and music aficionado – decided he wanted to record some of the sounds that captured the energy of New York’s buzzing nightlife.

In 1948, Goldner teamed up with the radio DJ and personality Art “Pancho” Raymond, and they launched Tico Records out of offices at 659 Tenth Avenue. Because Goldner had a sense of what was happening in dance halls, Tico Records’ earliest label luminaries reflected the best of the “cuchifrito circuit,” the nickname for the collection of after-hours clubs and underground spots where aspiring Latin musicians performed. Tito Rodríguez, Tito Puente, and Machito were among the first artists to release albums on the label, with Puente, in particular, drawing more talent to the Tico umbrella. He began recording with both La Lupe and Celia Cruz in the 1960s, two powerhouse women today make up some of the most revered names in salsa music.

While the talent roster is undeniable, the label went through a series of changes and difficulties, morphing throughout the decades. In 1957, with debts piling up because of gambling habits, Goldner sold shares of his labels, including the Tico imprint, to Morris Levy. Goldner remained involved creatively, but in 1974 Tico was sold to Fania Records. Tico was an early home to artists that became salsa icons, particularly Afro-Cuban stars who serve as testament to the significance of Latin music’s Black roots. Less successful, but intriguing recordings from later years include Dominican merengues, South American tangos, and Mexican regional music, adding up to an expansive catalog that is timeless and full of gems to discover decades later.

Listen to highlights from Tico Records on Apple Music and Spotify.

The Mambo Kings

Tico Records signed its first artist, Tito Rodríguez, in 1948. Rodríguez, born in Santurce, Puerto Rico to a Dominican father and a Cuban mother, was a bandleader and veteran of the club circuit. He also helped popularize mambo – which Tico Records would quickly corner the market on. After Rodríguez gave Tico its very first release, “Mambos, Volumen 1,” the label signed another club veteran with a thing for mambo and cha cha: the Harlem-born percussionist Tito Puente. Puente would provide Tico Records with its first hit when he released 1949’s “Abaniquito,” a song that blended mambo and Afro-Cuban rhythms in a way that foreshadowed how many artists would approach salsa rhythms.

While the two Titos are often remembered together, the Afro-Cuban legend Francisco Raúl Gutiérrez Grillo – otherwise known as Machito – also lives in the Mambo King lore. Machito, who was born in Cuba and arrived in New York City as a teen, was known in the club circuit for performing with his band, Machito and His Afro Cubans. They were pioneers in many ways, incorporating congas, bongos, and timbales into complex arrangements, and they often experimented with jazz sounds. As frequent headliners at the Palladium Ballroom, Machito also became known for mambo, which he brought to his early records on Tico. Machito, however, was a versatile, dexterous musician who was never afraid to try something new, like boogaloo and bossa nova.

The Queens of Soul And Salsa

In the 1960s, the legendary percussionist Mongo Santamaría was reading the Cuban magazine Bohemia when he came across a piece about a Cuban vocalist who was said to get possessed by spirits when she was onstage. The singer was the electrifying performer La Lupe, who had just arrived in New York City. She made a name for herself in New York City quickly, performing with Santamaria at mainstays such as the Apollo Theatre, Club Triton, and Palladium Ballroom, and it wasn’t long before Tito Puente fell under her spell and stole her away from Santamaria’s outfit.

Together, they recorded 1964’s “Que Te Pedi,” a song that puts the full power of La Lupe’s registry on display. La Lupe appeared alongside him on a few Tico Record releases, including Tito Puente Swings/The Exciting Lupe Sings, Tu Y Yo, and Homenaje a Rafael Hernandez, before Tico Records gave her a platform as a soloist. Her solo debut was 1966’s La Lupe Y Su Alma Venezolana, a surprising recording made up primarily of acoustic folk songs such as “El Piraguero” that allowed her to show off both the sheer belting power and vulnerability that were an inextricable part of her artistry.

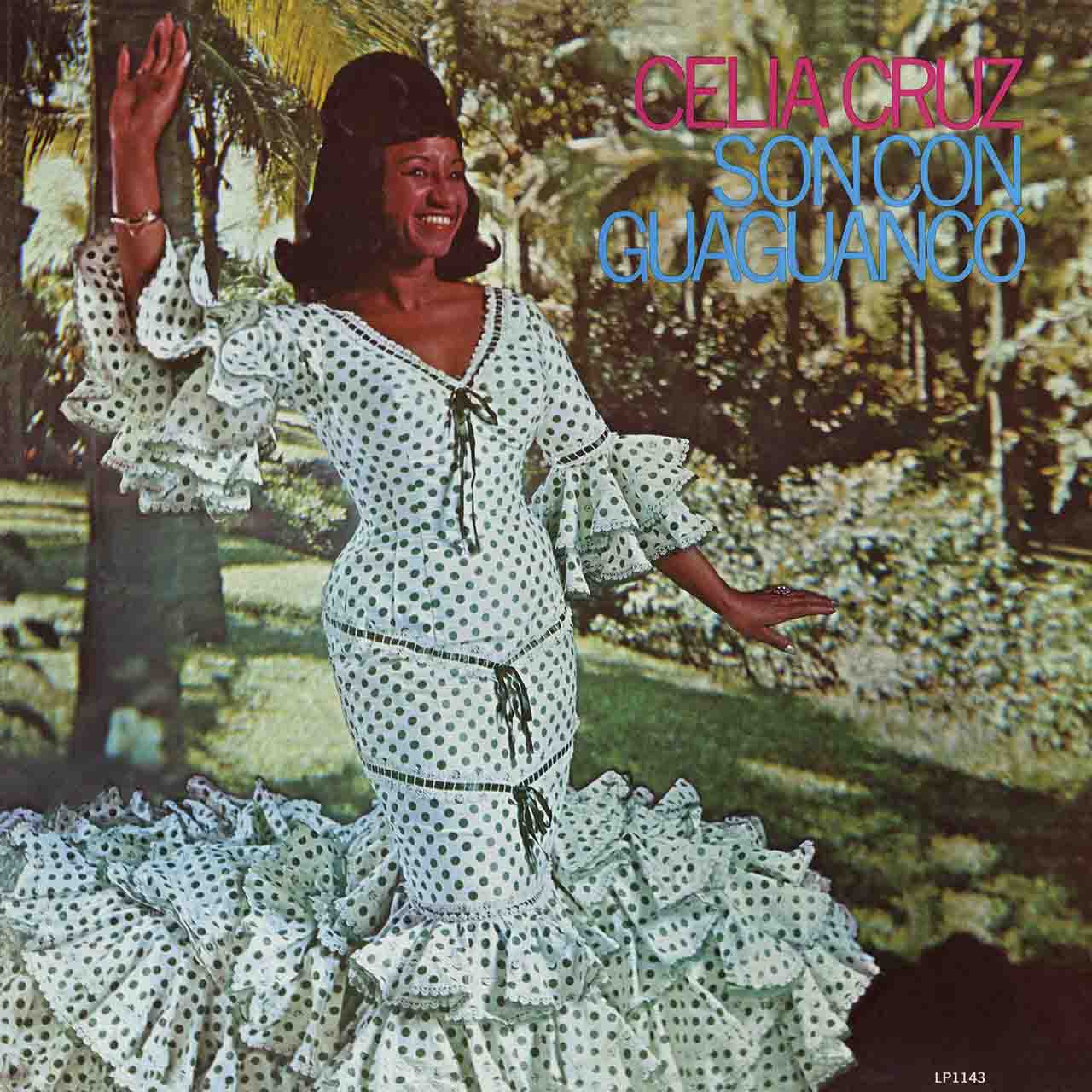

It’s common to pit La Lupe against Celia Cruz, the Cuban singer whose career began budding in the 1960s as well, but both inimitable women deserve their own place in salsa’s history. Cruz had already built a reputation performing with Sonora Matancera in Cuba, taking her place as the band’s first Black frontwoman. She left Cuba amid the revolution and was denied reentry onto the island, eventually landing in New York City in 1962. There, she connected with Puente and eventually made her solo debut on Tico with Son Con Guaguancó, the classic record that put African and Afro-Latin traditions at the forefront, such as on the charging “Bemba Colorá.”

The Wild Cards

Tico Records is filled with many albums that feel like spontaneous, exciting experiments. After Goldner worked to sign Puente and Rodríguez to new contracts, he also discovered a new up and comer: the New York pianist Joe Estévez, Jr., also known as Joe Loco, who added diversity to his arrangements by playing with jazz and pop sounds on the energetic “Hallelujah” and “I Love Paris” from his record Joe Loco and His Quintet: Tremendo Cha Cha Cha.

In 1962, Tico Records also saw success with “El Watusi,” a song from the Tico debut of none other than Ray Barretto. The Brooklyn-born conguero had made a name for himself playing in clubs and jam sessions, fostering his interest in Latin sounds as well as jazz and bebop. He formed his own band, Charanga La Moderna, in 1962, and the “El Watusi” became his first hit. Though Barretto expressed ambivalence about it years later, it reached number 17 on the charts – and set Barretto on a path to become one of the most famed and eclectic Fania legends.

Tico Records also signed Eddie Palmieri after his conjunto La Perfecta disbanded. His first few releases, including 1968’s Champagne contained touches of boogaloo, a genre the pianist later decried as “embarrassing.” However, he showed off his penchant for risk-taking on the 1970 classic, Superimposition, where he melded Puerto Rican traditional rhythms, such as bomba, with jazz, pachanga, and more. Other standouts on the label include Bienvenido, a joint debut from Rafael Cortijo and Ismael Rivera, the sadly short-lived duo who paid homage to their Afro-Puerto Rican roots on percussive songs such as “Bomba Ae” and “Borinquén.”

Tico’s forays with artists from other parts of the Spanish-speaking world, including Argentina, Mexico, and Spain, resulted in few commercial hits. However, records such as the tango revivalist Astor Piazzolla’s Take Me Dancing and the Mexican ranchera singer Jose Alfredo Jimenez’s Down Mexican Way are fascinating capsules of other genres of Latin music that enrich Tico’s legacy.