The first time many people heard Alex Chilton’s name was thanks to a Replacements song from 1987, called “Alex Chilton.” The song was warm and proudly fanboyish, imagining Chilton as a star that “children by the millions” were lining up to see at a time when the man himself was drawing hundreds at best. Whenever he was asked about it, the former Big Star icon would reply with an audible shrug: “Yeah, I liked the song. It was one of their good ones.”

If indifference toward stardom makes you a purer artist, then Chilton was about the purest there was. He refused to make nice when he didn’t feel like it, and wouldn’t play any music he didn’t enjoy hearing. That led to him having one of the least predictable careers in all of pop music. There’s barely a false note in his catalog, even if it takes an open mind to embrace all of it.

A teenaged contrarian

Chilton’s attitude about stardom perhaps stems from his early brush with it. More than just a hitmaking band, The Box Tops became the template for a host of blue-eyed soul groups that sprung up in the Memphis area, and their 1967 breakthrough, “The Letter,” remains a perfect record (all 1:57 of it). That’s partly down to Chilton’s gravelly lead vocal; he was just 16 and doing his darnedest to sound older.

Chilton’s legendary contrariness was already in place. Check the band performing it on the Cleveland-based TV show Upbeat, in 1967, where a surly-looking Chilton is clearly not into lip-synching and starts mouthing stuff that has nothing to do with the record.

The group had a second smash, “Cry Like A Baby,” but their non-hits are at times even better. A psychedelic song in praise of prostitution? Sure. “Sweet Cream Ladies, Forward March” wasn’t about to top the charts, but it earned a place on all the latter-day Box Tops compilations. Ditto the more wholesome “I Met Her In Church”: a jubilant bit of rockin’ gospel.

A Big Star

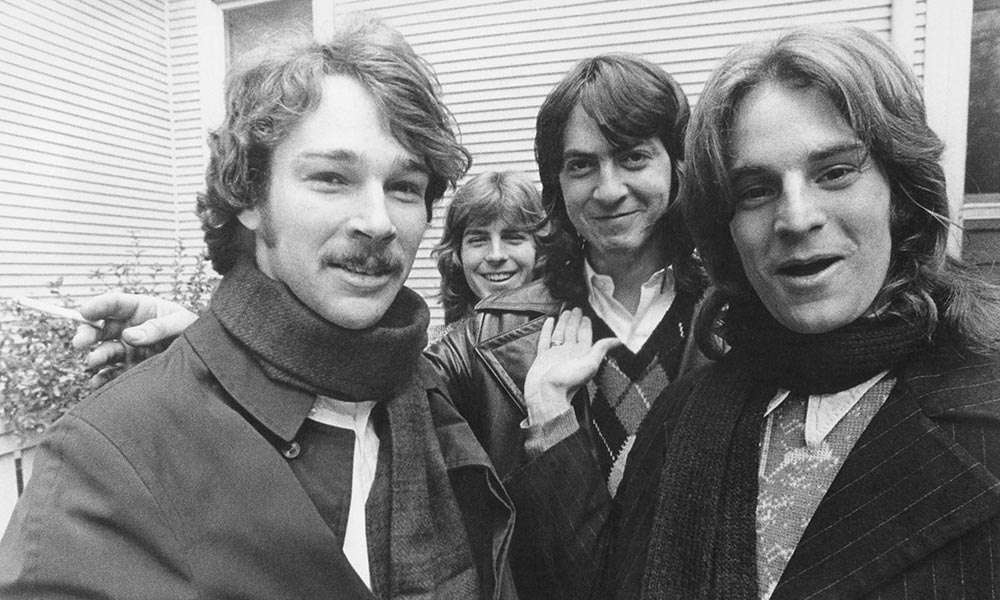

It was, of course, Chilton’s next band that cemented his legacy, even if hardly anyone recognized it at the time. Formed in 1971, Big Star is now the most hallowed name in power-pop, one of a small handful of pioneers (Todd Rundgren, Dwight Twilley, Badfinger, Raspberries) from which all power-pop derives. Their first two albums, #1 Record and Radio City, have recently been reissued on vinyl in the US, and remain go-tos for everyone from R.E.M. to KISS.

Yet there was much more to Big Star than soaring melodies and youthful romance. Over the course of three albums – each one darker than the last – they grew from singing carefree pop to gritty roadhouse rock, to yearning, bottomed-out catharsis. And thanks to Chilton and early co-writer Chris Bell, there was a bit of an undertow even in their most Beatles-like tracks. How many pop stars were singing about seeing a psychiatrist? And in the first line of a love song, no less? “Don’t need to talk to my doctor, don’t need to talk to my shrink,” Chilton sings in “When My Baby’s Beside Me.”

Anti-pop tendencies

That leads us to the next stage of Chilton’s career. The one that might be called the “really messed-up period.” Now living in New York and under various influences, Chilton veered as far from melodic pop as you could get. His album from this era, Like Flies On Sherbert, was all blues and country, and deliberately played with a minimum of coherence; the “sherbert” in the title was a nicer substitute for the word he wanted to use. Yet Chilton did manage a perfectly tuneful (and very funny) single at this time, “Bangkok.” Produced by young fan Chris Stamey, later of The dB’s, “Bangkok” became a staple of Chilton’s live sets.

Another artifact from this era recently slipped out in a 2019 collection called The Death Of Rock, a reluctant collaboration between Chilton and Peter Holsapple (also of The dB’s) that includes unearthed recordings from a 1978 session at Sam Phillips Recording Service in Memphis. The Death Of Rock is essentially a battle royal between pop and anti-pop tendencies. One of these two guys cares deeply about Chilton’s legacy with Big Star, and it sure isn’t Chilton.

Ahead of his time

As it turned out, Chilton was ahead of his time once again. His shambling work from this era anticipated the psychobilly movement, which he kicked off by joining Tav Falco’s Panther Burns and producing a young band called The Cramps. He also oversaw a Replacements session that didn’t work out, but the group still loved him enough to write the song afterwards.

Flash-forward a few years, and Chilton moves to New Orleans, where he cleans up and takes a job washing dishes. When he does start playing music again, it’s with a local rhythm section consisting of bassist Rene Coman and drummer Doug Garrison, who’d become the backbone of The Iguanas and helped Chilton realize a whole new musical slant.

Now a first-division roots rocker, Chilton was likely to greet any shouted requests for Big Star songs with songs by Slim Harpo, Willie Tee or whatever his passion was at the moment. Few things at the time were funnier than watching him serenade a houseful of Big Star obsessives with his purposely exaggerated rendition of the Eurovision hit “Volaré.”

The NOLA years

Once again, Chilton refused to get too respectable. In 1987 he released the couldn’t-possibly-be-a-hit single “No Sex,” a dark reference to AIDS paranoia, and in 1999 he made an album of vintage R&B covers – all of it lovingly played and beautifully sung – and gave it a title that’s NSFW but was renamed Set for its US release.

If you saw Chilton on a good night, he’d take you to roadhouse heaven, pulling great songs from everywhere (including his own back catalog) and nailing them all. In New Orleans he was also known for taking the stage when R&B legends were in town. He once played impeccable guitar with Brenton Wood of “Gimme Little Sign” fame, keeping his back turned so as not to upstage an artist he respected. Another posthumous release, Electricity By Candelight, catches Chilton at a magical Hoboken show where the power failed and he played acoustic, in the mood to hang with fans and sing his heart out.

Bittersweet reunions

The two things nobody expected Chilton to do was reunite both The Box Tops and Big Star. So, of course, he did both. The Box Tops performed a few occasional shows and made a new album, Tear Off!, in 1998. In 1993, Chilton rebooted Big Star with former bandmate Jody Stephens, along with Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow of The Posies, to play one show that turned into 17 years’ worth of on-off gigs.

They were, in fact, set to appear at South By Southwest in 2010, before Chilton’s sudden death threw a major damper on that year’s event. Then, in 2005, Big Star also made a new album, In Space, a divisive release among fans. Both the Big Star and Box Tops comeback albums sound more like each other than the original incarnations, and yet both bands sound like they’re having a hell of a time. And that, as we’re sure Chilton would maintain, is the best reason to do anything.

Listen to the best of Big Star on Apple Music and Spotify.