Before becoming the godfather of yacht rock, Jimmy Buffett released seven mostly unnoticed albums where he came off like a cross between an outlaw country rebel and a character from a late 60s underground comic book, with songs criticizing materialism, religious hypocrisy, and jingoistic politics, and extolling the glories of getting high, having as much sex as possible, and being a thorn in the side of the law. How did Buffet go from fabulous furry freak brother to laid-back pope of the Parrotheads?

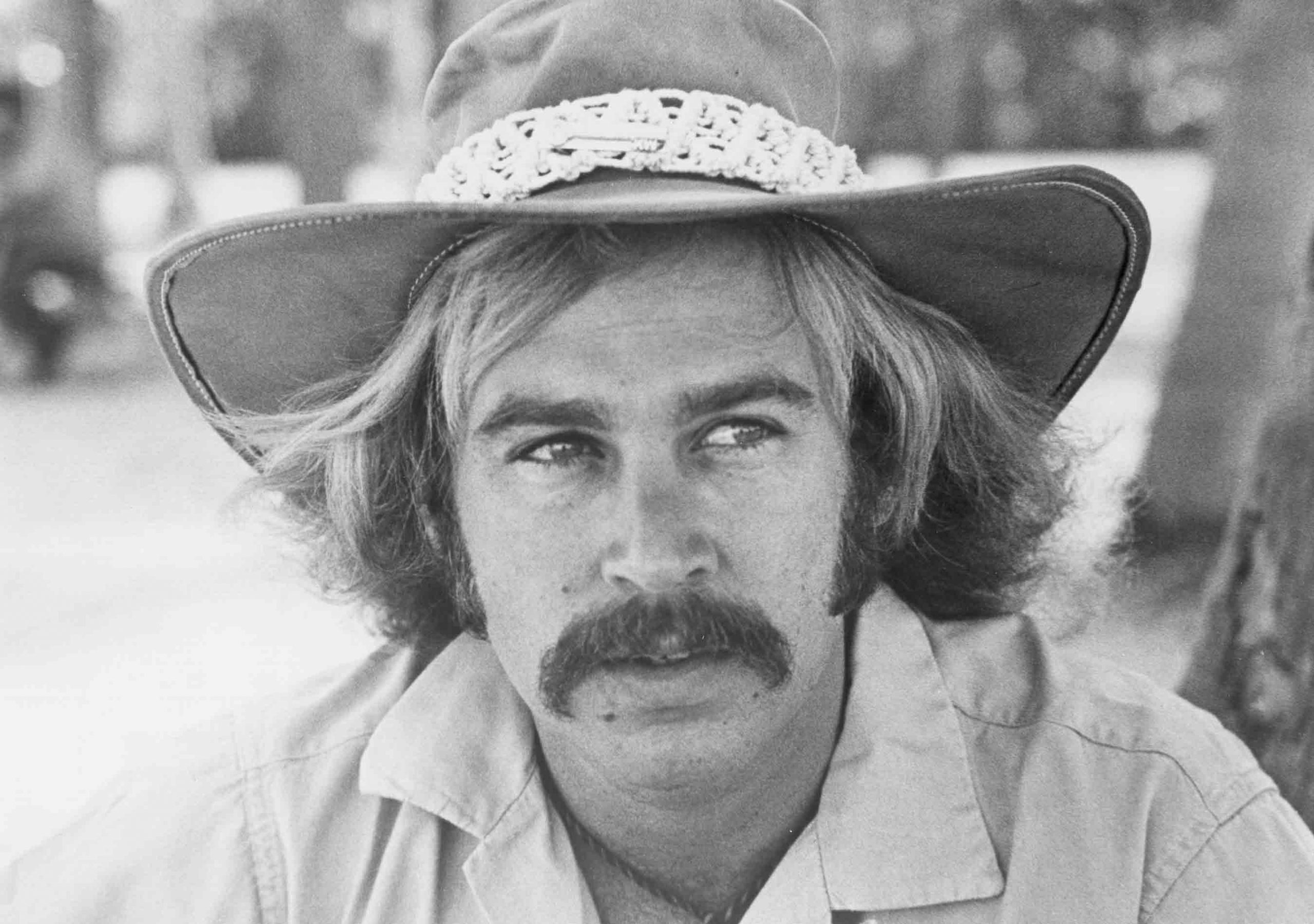

Long before “Margaritaville” led to legions of Hawaiian-shirted followers embracing him as their guru, Buffett was a hirsute hippie troubadour struggling to make a name for himself in Nashville. He hit Music City at the right time. A couple of years earlier, a countercultural type like him would’ve been run out of town. But revolution was on the rise, and scruffy songpoets like Kris Kristofferson were bringing folk and rock influences and a new kind of attitude to country music.

Listen to the best of Jimmy Buffett now.

Mississippi-born, Alabama-bred Buffett was in thrall to the thoughtful balladry of Gordon Lightfoot at the time, but his deep Southern roots added a country spin to his sound. He got a deal with Barnaby Records, owned by pop star Andy Williams. The result was 1970’s Down to Earth, a collection of stripped-down, contemplative country-folk tunes analyzing the Vietnam conflict (“The Missionary”), religious zealotry (“The Christian”), drug addiction (“Ellis Dee”), the persecution of hippies (“Truckstop Salvation”), and the nation’s tarnished reputation (“Captain America”).

Accounts of the album’s actual sales differ but they all concur that Down to Earth didn’t surpass three figures. Buffett gamely cut a follow-up, but the label allegedly lost the masters. “I never did think they’d lost it,” Buffett told American Songwriter decades later, “But I couldn’t really blame them.”

Bloodied but unbowed, Buffett eased down to Key West, Florida, where he found his groove. Working as a sailor, a street busker, and a barroom balladeer, he reveled in the laid-back lifestyle and let the ocean breeze of the Keys blow through his hair while he soaked up inspiration.

“It was still a Navy town,” he later told U.S. News & World Report. “It was a gay town. It was a hippie town. It was a local fisherman’s town. You want a melting pot? It was just that. It never ceased to give me ideas or…stories from which those first songs came.” Buffett’s manager sent some of those songs back to Nashville, where they fell on sympathetic ears and earned the beach-bum bard a new deal with ABC/Dunhill.

It was 1973 and the outlaw country movement had gained full steam with the rise of mavericks like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Tompall Glaser. Again the time seemed right for Buffett’s left-of-center country-tinged tunes. He recorded A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean at Glaser’s studio in Nashville, but it was the start of what’s known as the Key West period of his discography.

Musically, only “Cuban Crime of Passion” points toward the tropical vibe Buffett was beginning to brew, but the cover’s fishing boat backdrop provided a visual hint of things to come. Buffett wrote the waltz-time character study “Railroad Lady” with his buddy Jerry Jeff Walker. Another portrait of a colorful traveler, “He Went to Paris,” would be covered by Waylon and hailed by Bob Dylan.

Buffett leans full bore on his hedonistic hippie side with the casual-sex anthem “Why Don’t We Get Drunk,” which was way too suggestive for radio play (the title phrase is finished by “and screw”) but became an underground favorite. Add the two-stepping account of an ill-conceived gas station robbery on “The Great Filling Station Holdup” and the grocery store shoplifting memories of “Peanut Butter Conspiracy” (its title obviously inspired by the 60s psychedelic band of the same name), and Buffett seemed like what would happen if Robert Crumb created an outlaw country antihero for an early 70s issue of Zap Comix.

The next album, 1974’s Living and Dying in ¾ Time, boasts another boat-bedecked cover and more Key West-inspired tunes. Pickup trucks and whaling boats share space in the lyrics, but the sonic framework is steel guitar- and harmonica-heavy, with nary a nod to the Caribbeana to come a few years down the line. The gentle, strings-swathed “Come Monday” edged into the Top 40, giving Buffett his first hit. “Brand New Country Star” is a wry, honky-tonking snapshot of a country-to-rock crossover, and the rocking “Saxophones” shoots the listener a wide grin, blaming the lack of the title instrument for the singer’s unpopularity on his Alabama home turf (a greasy sax section duly arrives to save the day before the end of the song).

The album closes with two covers that hint at Buffett’s influences: Texas country-folk cult hero Willis Alan Ramsey’s “Ballad of Spider John” and legendary beatnik monologist Lord Buckley’s spoken-word-plus-jazz shaggy dog story “God’s Own Drunk.” Word of Buffett’s ballsy twang reached all the way to England, where Bob Woffinden wrote about the record in the New Musical Express, “He’s one of the new breed of country singers whose sense of a Larger Reality is helping to broaden the scope of Nashville country music.”

With a leg up from the success of “Come Monday,” the next LP, A1A, climbed higher into the charts than any Buffett album before it, but still didn’t produce a hit single. Displaying some self-fulfilling prophetic powers, it opens with a wide swipe at careerism, country rocker “Makin’ Music for Money.”

Buffett occupies a beach chair under a palm tree on A1A’s cover, leaving little doubt about his lifestyle choices, but musically he was still keeping it country for the most part. The push and pull pops to the surface on “Migration,” where Buffett sings, “Got a Caribbean soul I can barely control/And some Texas hidden here in my heart.” But before the song is done, Buffett is declaring allegiance to outlaw country, “Listening to Murphey, Walker, and Willis sing me their Texas rhymes,” referencing Texas-based tunesmiths Michael Martin Murphey, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Willis Alan Ramsey.

“A Pirate Looks at 40” is both a subtle step towards trop-pop and a major artistic achievement. It’s a perfect example of one of Buffett’s songwriting superpowers – the ability to make statements of dissolution and depression sound not just bittersweet but almost upbeat by contrasting them with a gentle musical lilt. Only in Buffettland could a tune with the following lyrics become an arms-aloft fan fave that he can’t leave the stage without playing to this day.

Yes, I am a pirate, 200 years too late

The cannons don’t thunder, there’s nothing to plunder

I’m an over-40 victim of fate

Arriving too late, arriving too late

I’ve done a bit of smuggling, I’ve run my share of grass

I made enough money to buy Miami, but I pissed it away so fast

Hit singles or no, Buffett’s profile had risen to the point where he was enlisted to provide the soundtrack for the 1975 contemporary Western film Rancho Deluxe, starring Jeff Bridges and Sam Waterston. The movie was an epic flop, but the soundtrack album is a fascinating curio in the Buffett catalog, an appropriately Western-flavored outing including instrumentals and early versions of songs he’d revisit later.

Barnaby’s 1976 recovery and release of Buffett’s second, “lost” recording, High Cumberland Jubilee, five years after its disappearance, was attributable to either a stroke of providence or Buffett’s increased prominence, depending on your level of cynicism. Either way, it’s another great example of his early 70s folk-rock feel, flowing freely with hippie sagas. “The Hang Out Gang” views a commune crew of barefoot “gypsies” through the eyes of smallminded locals, and “Rockefeller Square” is an uptempo takedown of a child of privilege slumming in the freaky underground.

But the proper follow-up to A1A, 1976’s Havana Daydreamin’, finds Buffett within months of a critical inflection point. On one hand, he’d seldom sounded more like an outlaw country archetype than on the good-time barroom stomp-along “My Head Hurts My Feet Stink and I Don’t Love Jesus,” a morning-after account of a wild night of country pickin’ and Olympic-level elbow bending.

At the same time, the title track, with its breezy island sway and its account of Illicit activities in a tropical setting, seems like the first half of a layup that would be completed in ‘77 with the arrival of “Margaritaville.” Still, as late as mid ‘76, Toby Goldstein was making Buffett sound like the lost member of Dr. Hook, writing in Sounds that “Buffett’s humour follows along the lines of his album titles, as his tunes devote themselves to groupies, mothers, and quaaludes.”

Havana Daydreamin’ neither lit up the album charts nor produced anything like a successful single. If his career had ended right there (which would not have been unthinkable if the winds hadn’t shifted so sharply), we would celebrate Jimmy Buffett as one of the great, underrated country outlaws. But the man who seemed to have spent the first half of the 70s bent on becoming Florida’s answer to Kinky Friedman was just one cocktail and a busted flip flop away from a complete sea change.