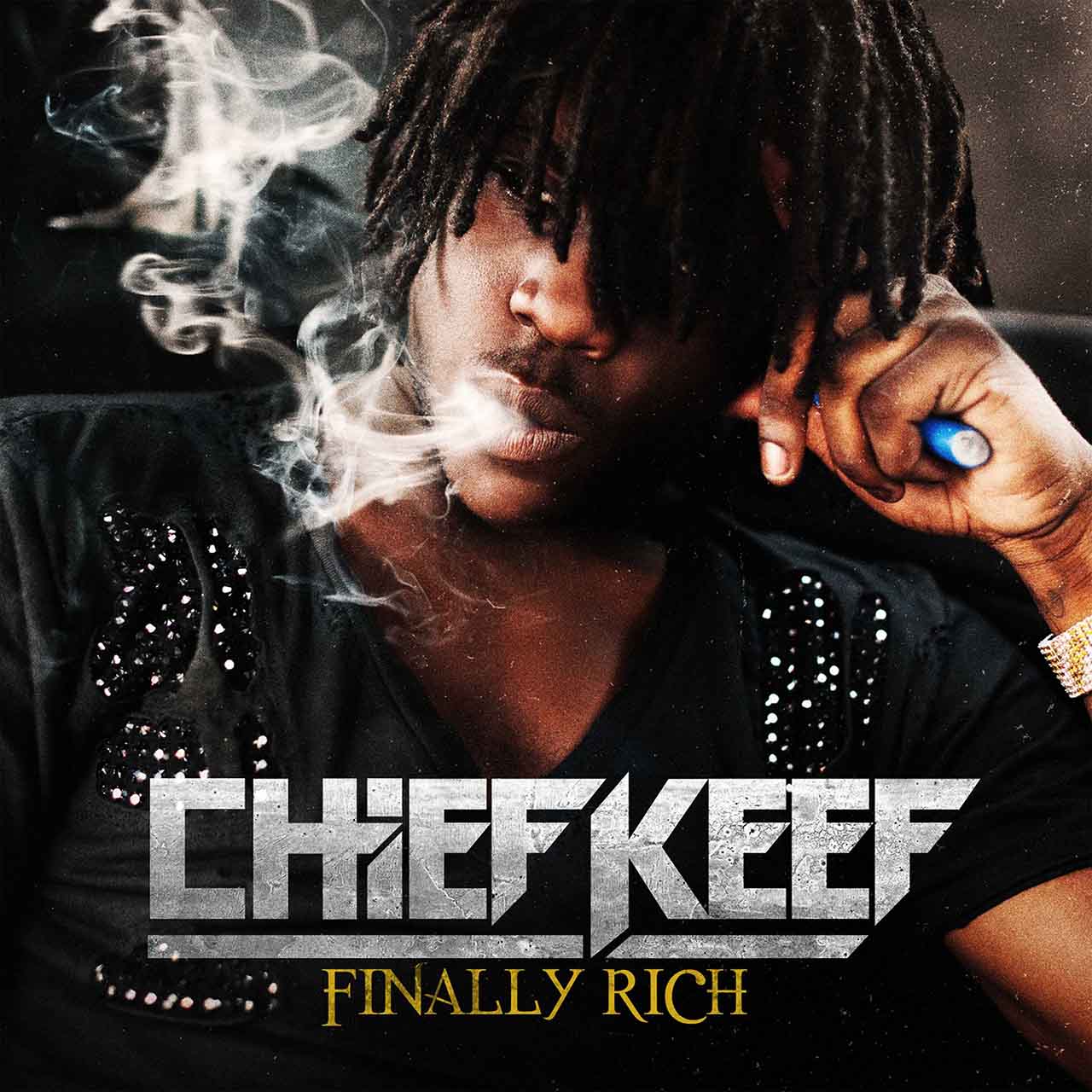

One day, my grandchildren will roll their eyes as I launch into my 300th re-telling of what it was like to be alive in Chicago in 2012. But things were happening, and you could feel it. One of the best rap shows I’ve ever witnessed was in the spring of 2012, at the now-shuttered Congress Theater; technically, the night was headlined by Meek Mill, but for all practical purposes, it was a showcase for local rappers whose buzz had become deafening: King Louie, Lil Durk, Lil Reese, Fredo Santana, and most of all, Chief Keef, the dread-headed, Gucci-belted 17-year-old rapper who’d arrived in an ankle monitor. (Still on house arrest at his grandma’s, he’d gotten permission from the Chicago Police Department to perform that night – the last time the CPD would treat the rapper with anything remotely resembling empathy.) Midway through the show, the paranoid fire department locked down the venue, trapping everyone inside. When Keef finally appeared on stage, flanked by about 50 of his closest friends, the room went electric; when he performed “I Don’t Like,” it felt like history was being made.

Still, to say the conversation around Keef, on both a local and national scale, was divided is to put it mildly. Critics called his early mixtapes dumbed-down, hyper-repetitive, artless, even suggesting they glamorized the violence that had plagued Chicago for decades. (“Why can’t he just be a role model and put the guns down?” was a party line heard again and again that summer, a profound misunderstanding of not just the city’s structural realities but the value of art.) By the time his major-label debut dropped in December 2012, the conversation around the teenager had become so frenzied and polarized that it felt like we’d lost the thread of what had made Keef so popular to begin with. (And no, it wasn’t hip-hop bloggers; Keef’s cult-like mass of devotees had been forged on the city’s South and West sides long before the notorious fan video that Chief Keef would ultimately sample on Finally Rich’s title track even hit WorldStar.)

Listen to Chief Keef’s Finally Rich here.

Far from glamorizing the surroundings that birthed him, Keef presented a world that was previously invisible to outsiders, exactly as it was – a world that had become thoughtless media pundit shorthand for the worst parts of America, an imaginary, dog-whistled war zone that had eclipsed any first-hand consideration of Chicago’s economic and police-sanctioned warfare as it actually existed. Keef resonated because his mere existence was anti-establishment: anti-industry (i.e., bailing on his own “Hate Being Sober” video shoot); anti-Chicago rap canon, as the antithesis of the city’s handful of existent superstars; and most of all, by not only surviving but excelling, an unignorable example of exactly the type of person who wasn’t supposed to make it.

To an outside audience, Finally Rich as a work was inextricably linked to the general perception of Keef’s Chicago – grim, violent, nihilist music, with martial Young Chop drums befitting the city that had come to be known as “Chiraq.” It was an understandable lens through which to view it all, but in retrospect, it distracted from elements that made Chief Keef’s Finally Rich one of the most impressive major-label rap debuts of the 2010s. Take “Kay Kay,” probably the album’s most underrated track, dedicated to Keef’s then-infant daughter. KE on the Track’s beat comes crashing in waves, with meditative piano loops and soaring synths that always reminded me of the Dipset Trance Party tapes. Keef’s half-sung vocals are processed to sound like a slurry android, with the paradoxical effect of heightening the humanity of it all. When he chants “Pullin’ up in our foreigns / Ig-NOR-ance,” he draws out the final word as though it’s a full sentence, bending the language to his will. It’s far more clever than he got credit for.

Many would call Finally Rich the peak of Chief Keef’s career, and suggest that his inglorious decline started almost immediately thereafter: jail stints, rehab, getting dropped from his record label, and being effectively banned from performing in his hometown, even in hologram form. Of course, this is only remotely true if your engagement with rap is solely limited to Billboard charts or whatever is fed to you by Spotify’s sterling caviar spoon. In fact, post-Finally Rich Chief Keef has only continued experimenting and making massively popular hits (see: “Faneto,” “Earned It”), following his every creative whim in between rounds of paintball. Meanwhile, the ripples of his cadences, flows, and adlibs – not to mention Young Chop’s production style – have, against all odds, deeply resonated among a new generation of rappers, touching not just the underground but the highest echelons of the mainstream. The list of benefactors of Keef’s style is endless, but a short version includes Lil Uzi Vert, Fetty Wap, Playboi Carti, 21 Savage, Yung Lean, Bobby Shmurda and the entire GS9 crew, an entire UK drill movement, Lil Yachty and DRAM’s “Broccoli,” Tay-K’s “The Race,” and pretty much the entire SoundCloud rap ecosystem.

Had “I Don’t Like” or “Love Sosa” been released in an era where streaming data factored into chart numbers, we might be approaching Finally Rich’s legacy, and Keef’s career trajectory, from an entirely different perspective. But then again, maybe not. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s not so much Finally Rich’s influence that makes it feel so important – in fact, it’s much more the contrary. What cements Finally Rich in the canon is Chief Keef’s stubborn commitment to his own vision, doing things exactly how he wanted them in an industry that wants to shove you down the masses’ throats. It’s that Keef never fell into that trap that makes him the legend he is today. “I’m finally rich, but ain’t a damn thing gonna change,” he rapped on the album’s titular outro – and he was right.

Listen to Chief Keef’s Finally Rich here.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2017.