After the countercultural dream of the late 60s came crashing down, the artists whose music had given that dream a soundtrack were all faced with the same question: What now? The era’s most iconic rockers all arrived at different answers on their first albums of the ‘70s. The Who, The Rolling Stones, two newly emancipated ex-Beatles – each had their own ways of managing the tricky transition from the idealism and adventurousness of the 60s to the reality of the new decade.

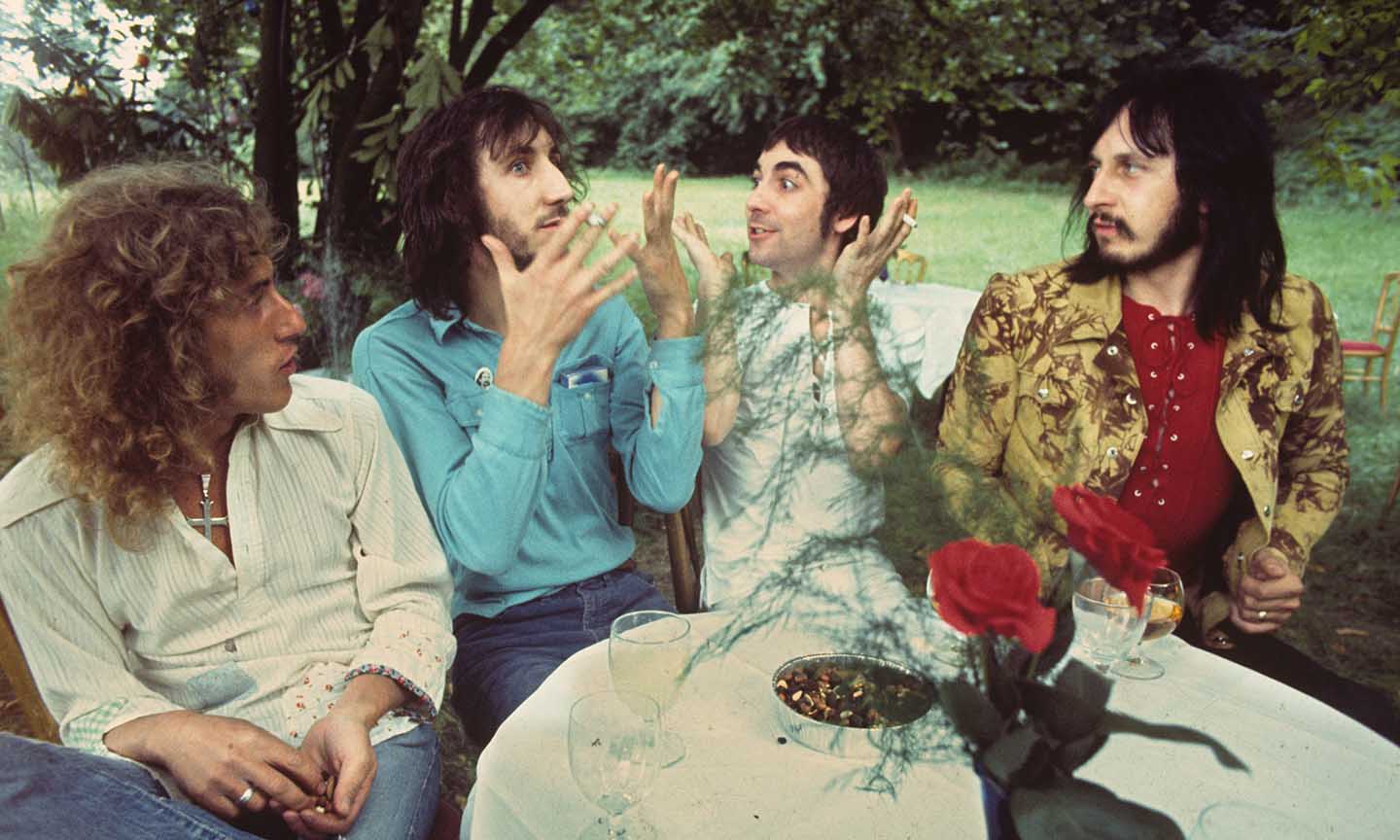

The Who

For The Who, the 60s had been a time of expansion and experiment, from their pioneering 1966 electric operetta, “A Quick One, While He’s Away,” to the tongue-in-cheek conceptualism of 1967’s The Who Sell Out and the full-blown, album-length 1969 rock opera Tommy. Along the way, they joined the psychedelic vanguard (“Armenia City in the Sky”), spun fanciful fables (“Silas Stingy”), crafted aural approximations of a day at the circus (“Cobwebs and Strange”), and put their own spin on everything from Motown hits to the Batman theme.

Who’s Next, the first Who album of the 70s, had its beginnings in an unrealized project that provides the perfect metaphor for the big ideas of the 60s crashing and burning on the shores of the next decade. Pete Townshend envisioned Lifehouse as a high-concept sci-fi rock opera that would make Tommy look like a nursery rhyme. It would have involved an album, a film, and some sort of interactive concert series, utilizing all the latest technology.

Like a lot of the period’s hyper-ambitious proposals, Lighthouse turned out to be a case of reach exceeding grasp. Nonetheless, a bunch of tunes were repurposed on Who’s Next for what may have seemed like an even more radical idea at the time: a regular ol’ rock album of self-contained songs. But before you even got to the music, it was obvious something had changed.

The Tommy cover was a mind-bending vision that could have floated straight out of somebody’s acid trip. On the cover of Who’s Next, the band stands amid a wasteland of mining rubble, where they appear to have just relieved themselves against a concrete pillar. Album photographer Ethan Russel has said that it was partly a sarcastic play on the famous monolith scene from 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Again, hippie idealism gives way to something markedly more abject.

Few songs chronicle the comedown from Aquarian Age ideals more effectively than “Baba O’Riley.” In 2021 Townshend told Guitar Player’s Christopher Scapelliti that the “teenage wasteland” of the lyrics is a reference to “the absolute devastation of teenagers at Woodstock, where everybody was smacked out on acid.” “Won’t Get Fooled Again” takes a similar tack. Casting a disillusioned look at the hippie revolution’s results, they observe, “History ain’t changed,” and wryly note that “The parting on the left is now a parting on the right/And the beards have all grown longer overnight.”

The sonic makeup of those two songs marks a major break with the past, too. Both tunes interrupt the band’s traditional guitar/bass/drums axis with Townshend’s electronic experiments involving almost Philip Glass-like minimalist repetition.

Listen to The Who album Who’s Next now.

The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones’ 70s entrée was a less drastic development but no less notable. On 1967’s Their Satanic Majesties Request, the Stones had flown their paisley flag as proudly as anybody. But they ended their 60s string with two back-to-the-roots records: Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed. Released just weeks before the 60s came to a close, the latter was really their run-up to the new decade. Its surrealist cover was still pretty damn psychedelic though, featuring Stones pal Robert Brownjohn’s fanciful cover photo of a crazy cake whose lower layers include a pizza, a clock, and a tire, all suspended above a Stones record being played by an old-school gramophone-style needle.

In stark contrast, the famous cover of 1971’s Sticky Fingers, designed by Andy Warhol, was a gritty, in-your-face evocation of sexuality: a crotch shot with a zipper that (in the original pressing) opened to reveal a layer of underwear. The songs inside were revealing in their own way, unshackling some of the Stones’ darker inclinations even as they continued down a rootsy, acoustic-tinged path.

It was the band’s first album without Brian Jones, who had died in July of 1969. Though Jones had been one of the band’s biggest blues boosters, he was also their imp of the perverse, the spirit egging them on to unexpected musical detours, even as early as his track-defining marimba on “Under My Thumb.” Not only were the Stones now missing that X factor, they were missing their departed friend.

You can hear it in the downcast mood hanging over tunes like “Sister Morphine” and “Dead Flowers.” The former’s nightmarish, minor-key moan about a hospital patient craving drugs and/or death has a lot to do with initially uncredited co-writer Marianne Faithfull’s contributions. In 2013 she told The Guardian’s Dave Simpson, “It isn’t exactly what happened to me, but my feelings about it are probably the same. I was hospitalized in Sydney after an attempted suicide after Brian Jones died. It was a terrible time.”

Gram Parsons, who would join Jones in the choir invisible in 1973, had become buddies with Keith Richards by the time of the Sticky Fingers sessions, and the influence of his brokenhearted country sound looms over tunes like “Wild Horses” and “Dead Flowers.” Mick Jagger has confessed he never felt completely credible as a country singer, so he camps up the latter a tad, but from its strikingly candid evocation of heroin use (“I’ll be in my basement room with a needle and a spoon”) to its macabre chorus, there’s no escaping the darkness.

Listen to The Rolling Stones album Sticky Fingers now.

Paul McCartney and John Lennon

The Stones’ old “rivals” didn’t make it through the 60s intact. The 1970 solo debuts from The Beatles’ creative core found both John Lennon and Paul McCartney stripping down and baring all in one way or another. McCartney couldn’t be further from the Fabs’ final recording, Abbey Road. The Beatles’ closing statement (recorded after Let It Be but released before it) was cut in the legendary studio that gave the record its title, and its pristine production was exactingly overseen by George Martin.

Conversely, the only way Paul’s first solo outing could have been more homegrown is if he recorded it in his garden. He did record it mostly at home, though, with a minimum of gear, engineering and playing everything himself. The result is an unassuming, ramshackle production in which classic McCartney tunes like the love-smacked “Every Night,” wistful “Junk,” and transcendent “Maybe I’m Amazed” are embedded among endearingly offhand tracks like the lo-fi garage-rock instrumental “Valentine’s Day” and the tongue-in-cheek percussive party of “Kreen-Akrore.” It was clear that the 1970 model McCartney was a man intent on letting it all hang out.

Listen to Paul McCartney’s album McCartney now.

Released eight months after McCartney, Plastic Ono Band actually brought Lennon back to Abbey Road, with a full band and the production assistance of an uncharacteristically reserved Phil Spector. But Lennon’s open-wound approach to the songwriting took the album even further from Beatles territory than Paul’s project. Determined to break with both the 60s and the band that defined them, Lennon rips his troubled soul open, looks deep inside, and lets listeners in on the outcome.

With bare-bones arrangements including Ringo Starr on drums, Lennon takes himself apart piece by piece, delving into his issues with his absent parents amid primal screams on “Mother,” the popping of the countercultural balloon on “I Found Out,” and his struggle to be more than an ex-Beatle on “God.” The latter song’s last verse is about as succinct a statement on the transition to the new era as any ‘60s rocker ever made.

I was the dreamweaver

But now I’m reborn

I was the walrus

But now I’m John

And so dear friends

You’ll just have to carry on

The dream is over