When Paul Weller split up The Jam – the biggest and most beloved band to emerge from the UK punk scene – in October 1982, it looked to some like an act of wilful self-sabotage.

Since their exhilarating April 1978 debut single, “In The City,” Weller, bassist Bruce Foxton and drummer Rick Buckler had connected with the masses in a way that no UK band had since The Beatles. Weller’s songs had become anthems, three-minute bursts of fury and energy that channelled the nation’s hopes and fears. What’s more, they were on a hot streak. Weller’s writing was sharper than ever, and their most recent album, March 1982’s The Gift, hit No 1, as did its lead single, the thrilling Motown homage “Town Called Malice.” “At the end of this year, The Jam will be officially splitting up, as I feel we have achieved all we can together as a group,” Weller wrote in a statement released on October 30, 1982. “I’d hate us to end up old and embarrassing like so many other groups do.” Weller was just 24 years old.

Weller’s decision was met with disbelief, but The Jam went out on a high. Their all-guns-blazing final single “Beat Surrender” went straight to No 1 on 4 December 1982, and their final tour of the UK (including five nights at Wembley Arena) was a triumph, with a cathartic final gig in mod Mecca Brighton on December 11, 1982. The following month, all of their singles were re-released in the UK; 12 of them re-entered the Top 100. But while fans mourned the end of The Jam, Weller was already planning his bold next move – he’d return months later as the leader of The Style Council.

The Style Council

“My ambition with The Style Council was to take on different kinds of music,” Weller said in the 2007 BBC documentary Soul Britannia. “I wanted to experiment and all the stuff I was hearing, I wanted to try, whether it was early rap or the 80s R&B soul thing that was going on; I was getting heavily into jazz. I just wanted to have a vehicle where you were free to go anywhere you wanted… I needed to have something that didn’t have constraints so I could try those things, that was the ambition.”

Inspired by European new wave cinema auteurs, Weller envisioned himself as their musical equivalent, the director of an ever-changing collective whom he could cast depending on his musical mood. He already had a right-hand man in place – keyboardist Mick Talbot, formerly of The Merton Parkas, Dexys Midnight Runners and The Bureau. Back in 1979, Weller had called Talbot out of the blue to ask him to play piano on The Jam’s cover of Martha & The Vandellas’ “Heatwave” (from Setting Sons). The following year, Talbot joined The Jam on Hammond organ for a bunch of soul covers during their shows at the Rainbow, London. Weller knew that Talbot had the chops to do their shared love of soul and funk justice, and, most importantly, had the right attitude. “He shares my hatred of the rock myth and the rock culture,” Weller told Record in 1983.

In March 1983, The Style Council released their glorious debut single, “Speak Like A Child.” From its opening seconds, it’s clear that this represented a new start for Weller, with funked-up bass, organ that sounds like rays of sunlight bursting through blinds, upbeat melodies, cooed backing vocals from Tracie Young, and a total lack of thrashing guitars. The video featured a giddy Weller dancing on an open-top bus, larking about with umbrellas and tickling Talbot – the serious young man of The Jam is long gone. Meanwhile, B-side, “Party Chambers” was a gorgeous piece of baroque pop with a 60s lounge feel (and surely the first Weller track to heavily feature flute).

Their second single, “Money-Go-Round,” went further still, with a relentless P-Funk groove, raunchy horns that nodded to prime James Brown and Weller rap-singing lyrics which bluntly spoke truth to power. The anti-capitalist message was as furious as anything Weller had previously written, but this was a tune to move your hips to, rather than pogo. His audience was perplexed, as he told Uncut in 1998, “With ‘Money-Go-Round,’ we bumped into a bunch of mod kids on Carnaby Street, and they were saying, ‘What’s all this jazz shit?’” Those young mods had a few more shocks coming their way.

Paul Weller’s love of soul

Before the split, Weller and The Jam were the figureheads of the mod revival movement in the UK. But as the scene became more focused on nostalgia than its original forward-thinking ethos, Weller had become disillusioned, as he told The Face in 1983, “All that ‘let’s have a fight on Brighton beach and pretend it’s 1963’ revivalism is rubbish. I still think of myself as a modernist — I have to try and elevate it! — but people have missed the point. The true mod legacy is all those soul boys and girls walking down the high streets, going to see the American soul bands that come over.”

The last few years had seen Weller return to the soul music of his youth, which opened up a whole new musical world. “[The Jam] had a DJ on the road with us, Ady Croasdell,” Weller told Mojo. “He turned me on to lots of stuff I hadn’t heard before, all these fantastic soul 45s and the first couple of Curtis Mayfield solo albums, hearing what an amazing poet he was, mixing poetry and politics.” Weller would give Croasdell, who was also a record dealer, lists of hard-to-find soul singles to track down and even asked the DJ’s girlfriend, who was a keen Northern soul dancer, to teach him some moves.

Inevitably, Weller’s infatuation informed his songwriting, with Jam tracks such as “Absolute Beginners,” “Town Called Malice,” “Trans-Global Express,” and “Beat Surrender” all indebted to soul classics. But The Style Council gave Weller the chance to find a more authentic soul sound. “When we first started, he had two boxes of 7-inch singles which were all relatively rare ’60s and ’70s soul, some Northern, some funk,” said Talbot. Nowhere is Weller’s love of Northern soul more pronounced than on the November 1983 single “A Solid Bond In Your Heart,” first demoed with The Jam (available on the 1992 rarities collection, Extras) but transformed into a storming homage worthy of the Wigan Casino dancefloor.

Meanwhile, another early Style Council single, the gorgeous “Long Hot Summer,” took its lead from mid-’70s ‘quiet storm’ soul, with Weller’s impassioned vocal drifting over a languid groove. “You know The Isley Brothers’ “For The Love Of You”? I think we were trying to sound a bit like that,” Weller later told Tom Doyle. The band’s early singles and B-sides were collected on the 1983 compilation Introducing The Style Council (released only in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Japan, and the Netherlands), which also featured a pair of club mixes – again emphasising Weller’s forward-thinking and eclectic approach to music.

Café Bleu

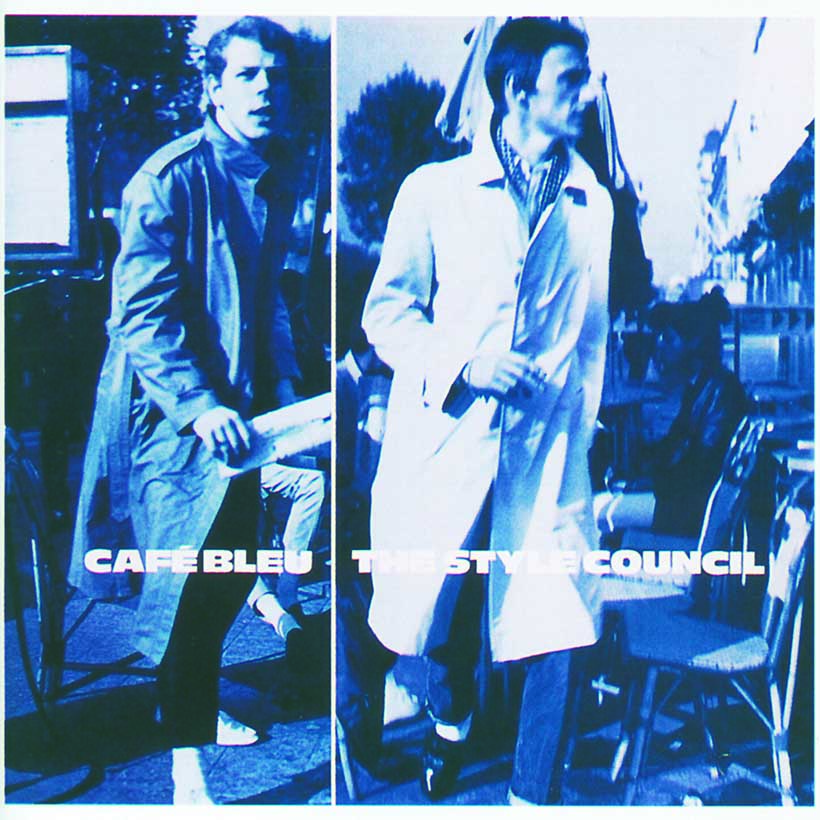

When it came time to make their debut album, Café Bleu (known in the US as My Ever Changing Moods), Weller strayed even further from his punk roots. “By the time of Café Bleu, we were trying to embrace jazz, such as it is,” Talbot told Mojo. “We didn’t see ourselves as jazz musicians; we were musicians who liked jazz.” The sleeve of Café Bleu, designed by Simon Halfon, spoke of Weller and Talbot’s love of Reid Miles’ classic Blue Note sleeves with its simple and stylish typography and tinted photography. In interviews, Weller namechecked the hard bop and cool jazz of the late ’50s and early ’60s – Cannonball Adderley, Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver – along with the early work of artists such as Donald Byrd and Herbie Hancock and Modern Jazz Quartet.

“The first side,” Weller told Neil Tennant of Smash Hits, “is supposed to be almost like a live sound, like a combo playing in a club.” Jazz is everywhere on Café Bleu – its opening track, “Mick’s Blessings” is a showcase for Talbot’s frisky fingerwork, with his jazzy piano front and centre over a walking bassline. “The Whole Point Of No Return,” “Blue Café,” and “The Paris Match” (featuring Everything But The Girl’s Tracey Thorn on vocals) are cool and languid, jazz-indebted ballads, while the edgy hard bop instrumental “Dropping Bombs On The White House” was brought to life by saxophonist Billy Chapman and trumpet player Barbara Snow.

Elsewhere, soul came to the fore on the Booker T & The MGs-style instrumental “Council Meetin’” and the giddy, Motown-inspired “Headstart For Happiness.” But most adventurous were a foray into electro-funk on “Strength Of Your Nature” and an attempt at hip-hop “A Gospel,” featuring rapper Dizzy Hite.

When Weller announced The Jam’s split, he emphasised his need for musical freedom. The Style Council’s early adventures, from those Northern soul-indebted singles to the jazz, hip-hop and funk leanings of Café Bleu, gave him exactly that. He’d shaken off the expectations of being in the most beloved band in the land and, from this point on, was free to pursue his ever-changing musical enthusiasms, wherever they took him.