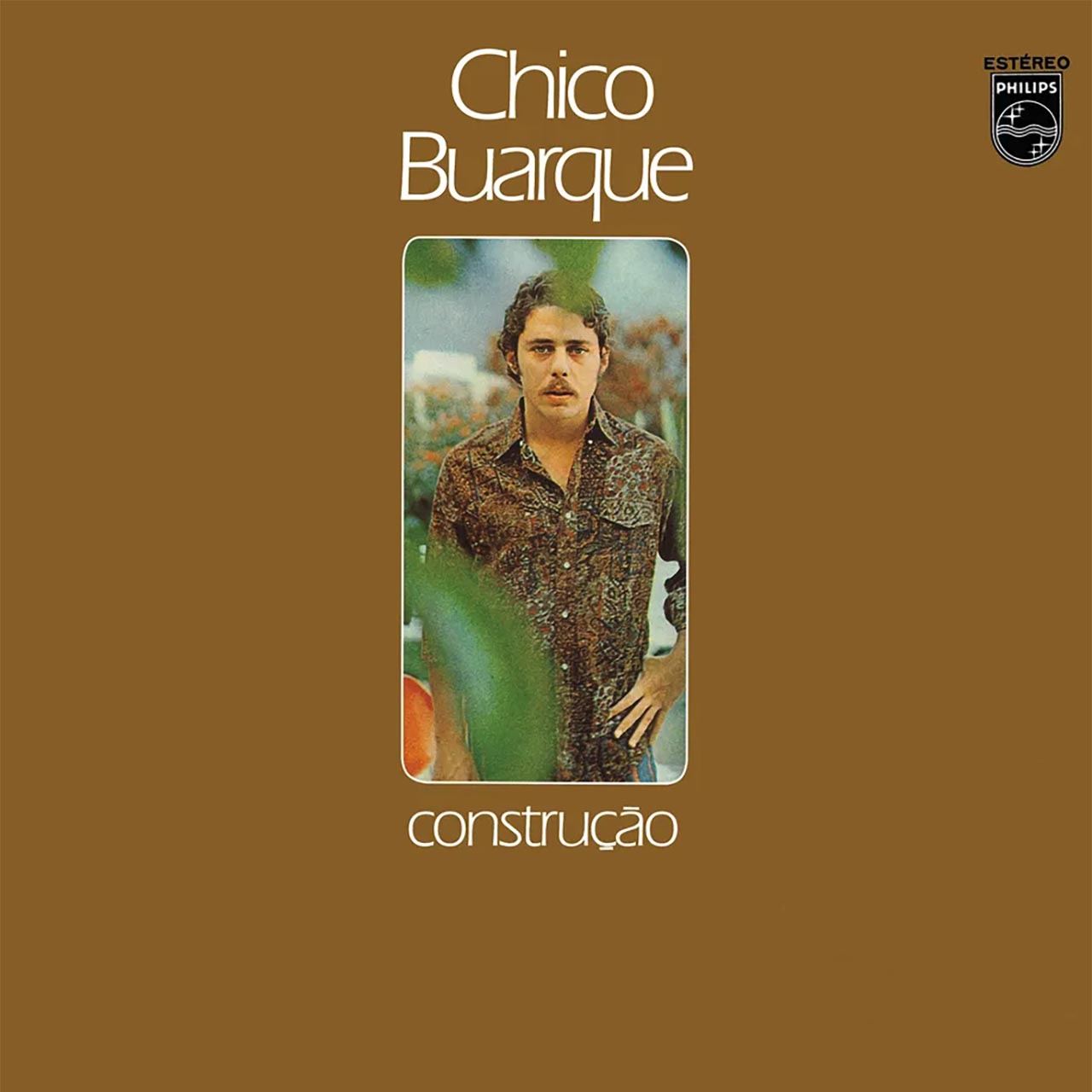

In 1969, Chico Buarque decided to extend a month-long vacation in Italy indefinitely. The self-imposed exile happened mostly for security reasons: A play he’d written had been deemed “subversive” by the Brazilian military regime. His fate closely mirrored his colleagues Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, who were living in exile in London. This didn’t mean Buarque had stopped working on music, however. Over the following 14 months, he recorded and released several albums, including Chico Buarque na Itália and Per Un Pugno di Samba, the latter containing Italian versions of some of his most well-known songs arranged by Ennio Morricone. During this time period, Buarque also wrote much of what would become his greatest album of all: Construção.

Despite his exile, Buarque wasn’t known as particularly subversive. In fact, his friends Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil criticized his early work for being relatively conservative. Construção was something else entirely, though. The album was a profound reflection on the country’s political situation via evocative imagery and incisive critique. It’s much more somber than his previous work, revealing a bitter mix of despair and revolt.

Listen to Chico Buarque’s Construção now.

Among the ten songs that comprise Construção is its epic title track, later named the best Brazilian song of all time by Rolling Stone Brazil. Through poetic schematics and intricate wordplay, the track unfolds in direct criticism of a repressive system, denouncing the dehumanization and alienation normalized by the mechanics of capitalism – even if Buarque confessed during a 1973 interview that his initial intention wasn’t as militant as it was eventually perceived. The rather simple yet efficient arrangements come from Rogério Duprat, a key figurehead of Tropicália, and provide a stark contrast with the complexity of the lyrics.

Construção benefits from other collaborations: Several tracks (“Valsinha”, “Samba de Orly,” “Desalento,” and “Olha Maria”) were written with Vinicius de Moraes. And there are guest appearances from Bossa Nova master Tom Jobim on “Olha Maria” and Toquinho in “Samba de Orly.”

Surprisingly, Construção managed to slip through the censors – a feat no doubt down to Buarque’s remarkable ability to wrap even his most acute commentary in lyrical ambiguity and melodic beauty. And the album became an instant success, selling 140,000 copies in the first month alone. The Phillips label had to hire the services of two separate pressing plants in order to keep up with demand.

The album is beloved by critics. Construção is regularly acclaimed as one of the best Brazilian albums ever. It’s no secret why: Construção occupies a pivotal place in Buarque’s career, marking the passage from his somewhat inconsequential poetics to a more visible social and political involvement. It also stands as a crucial piece of art to make sense of a dark period in the history of Brazil, painting a raw and powerful portrait of the era. Finally, a generation of artists have followed in its footsteps. It’s hard not to hear the influence of Construção in the work of Marcelo Camelo, Tim Bernardes, or Bala Desejo. Few albums have such a far-reaching legacy.