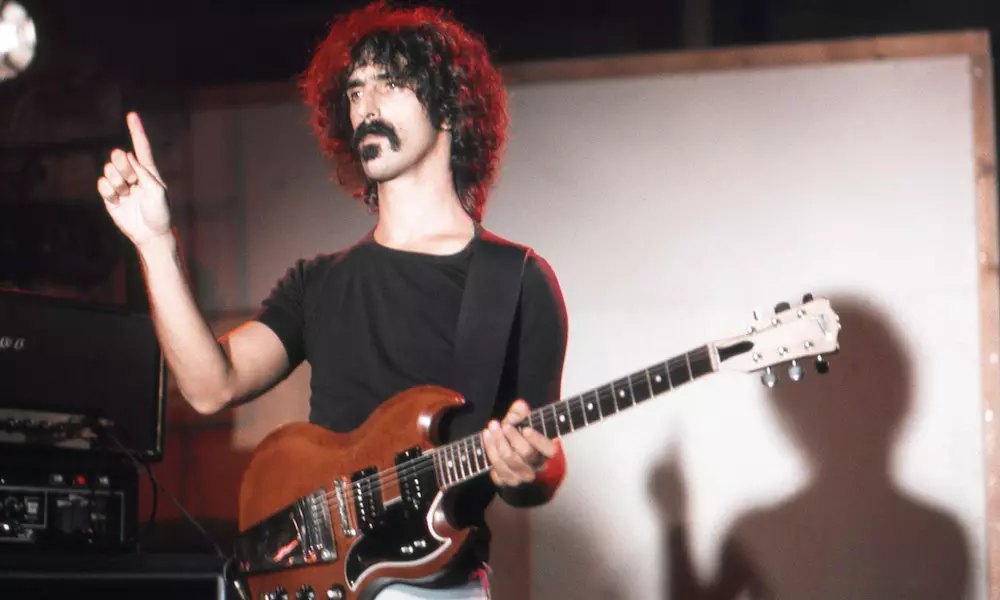

Bandleader, songwriter, composer, producer, record-company-owner, and potential President… Frank Zappa was all of these. He was also one of the first truly independent rock stars. Embodying the DIY spirit in everything he did, Zappa created his art purely on his own terms, cherry-picking the best musicians and the finest engineers to assist his lucid and insanely prolific workload.

Tom Wilson produced The Mothers Of Inventions’ first two albums (Freak Out! and Absolutely Free), but thereafter Frank took the rudder. He viewed his band members as his “actors”, with himself as producer/director (in the sleeve notes to Hot Rats he describes the album as “a movie for your ears”). Allied to this was his role as a pioneer of the avant-garde. 1966’s Freak Out! lays claim to be being among the first truly conceptual albums.

Oddball music and fastidious methods

Zappa was wholly preoccupied with the activity – and technology – of recording, production, and composition, so he was delighted when Sunset Sound and TTG Studios in Hollywood, as well as Whitney Studios, in Glendale, introduced 16-track recording. Zappa incorporated this technological breakthrough on 1969’s Hot Rats (by contrast, The Beatles recorded “The White Album” on eight-track, considering that an advance from their previous four- and two-track releases).

If Zappa’s oddball music and fastidious methods seemed playful or anarchic to outsiders, to their maker they were the opposite: method to his madness. Between 1960, and until his untimely death, in 1993, Zappa fronted a number of ensembles, including his own Mothers and the London Symphony Orchestra (his work with the latter was assembled from over 1,000 edits).

His own studio, built at a cost of 3.5 million dollars, afforded him the luxury of independence when it came to recording, and he employed two full-time engineers to man the boards. Though more expensive than using record company employees on an ad hoc basis, this approach at least meant that Zappa’s studio was manned and ready for use whenever he needed it. (The studio also boasted a specially constructed anechoic chamber in which Zappa could take naps between sessions, ensuring he never need be away from it when he didn’t want to be.)

Zappa could edit tape like nobody else

Longtime engineer Mark Pinske remarked that “Zappa could edit [tape] like nobody else”, and, in that sense, Zappa was a true postmodernist. On We’re Only In It For The Money, he skewered the hippies and their countercultural naivety while also baiting the authorities – a truly independent stance in the late 60s, in that Zappa pledged allegiance to neither camp. Nor did he restrict himself to just one musical style, his independent spirit cutting a course through ambient, musique concrète, surf, classical, doo-wop, and 50s rock’n’roll, plus music that edged towards difficult modernists such as Igor Stravinsky, Edgar Varèse, and the French electronic genius Pierre Henry.

Zappa often constructed albums with recurring themes and commentaries, the audio vérité-like results feeling as if the creative process itself was being captured as it happened. It gave his music a DIY feel before “DIY” became a buzzword. Indeed, Zappa pioneered the artist-run indie record label; though he used major labels for distribution and marketing, he also made deals that led to the birth of the Straight and Bizarre imprints, then DiscReet. These led to a slew of releases from the likes of Tim Buckley, The Amboy Dukes, and Ted Nugent, while Zappa also had a hand in bringing Captain Beefheart, Wild Man Fischer, Alice Cooper and The GTOs (Girls Together Outrageously) to the world. (The latter’s album, Permanent Damage, was produced by Zappa with contributions from Monkee Davy Jones, Lowell George, Rod Stewart, Jeff Beck and Ry Cooder.)

Absolutely free

Favoring freedom of speech (he fought the PMRC’s “Filthy Fifteen”) and independent business strategies, Zappa even considered running for President on an indie ticket.

In his memoir, The Real Frank Zappa Book, he stated, “There are millions of people who love music, but have tastes which differ from the ‘corporate ideal’ – that’s where independent labels come in. However, unless an independent is distributed through a major label, chances are the retailer is not going to pay on his ninety-day account – unless the independent has another hit coming in the door next month. The independent usually doesn’t, but the major label might, and it is this leverage that gets the bills paid.”

Following Zappa’s death, his wife, Gail, set off in his footsteps, setting up the Zappa Family Trust and releasing 38 previously unheard albums from the vaults. A deal with Universal Music Group ensured that, as Zappa himself stated, the indie venture was distributed by a major label. Working together, they have embarked on a series of releases that ensure the Zappa catalog is being curated the way it deserves.

Absolutely free? Certainly. From creativity to business practices, Zappa’s independent mindset blazed a trail for many that followed.

Listen to the best of Frank Zappa on Apple Music and Spotify.