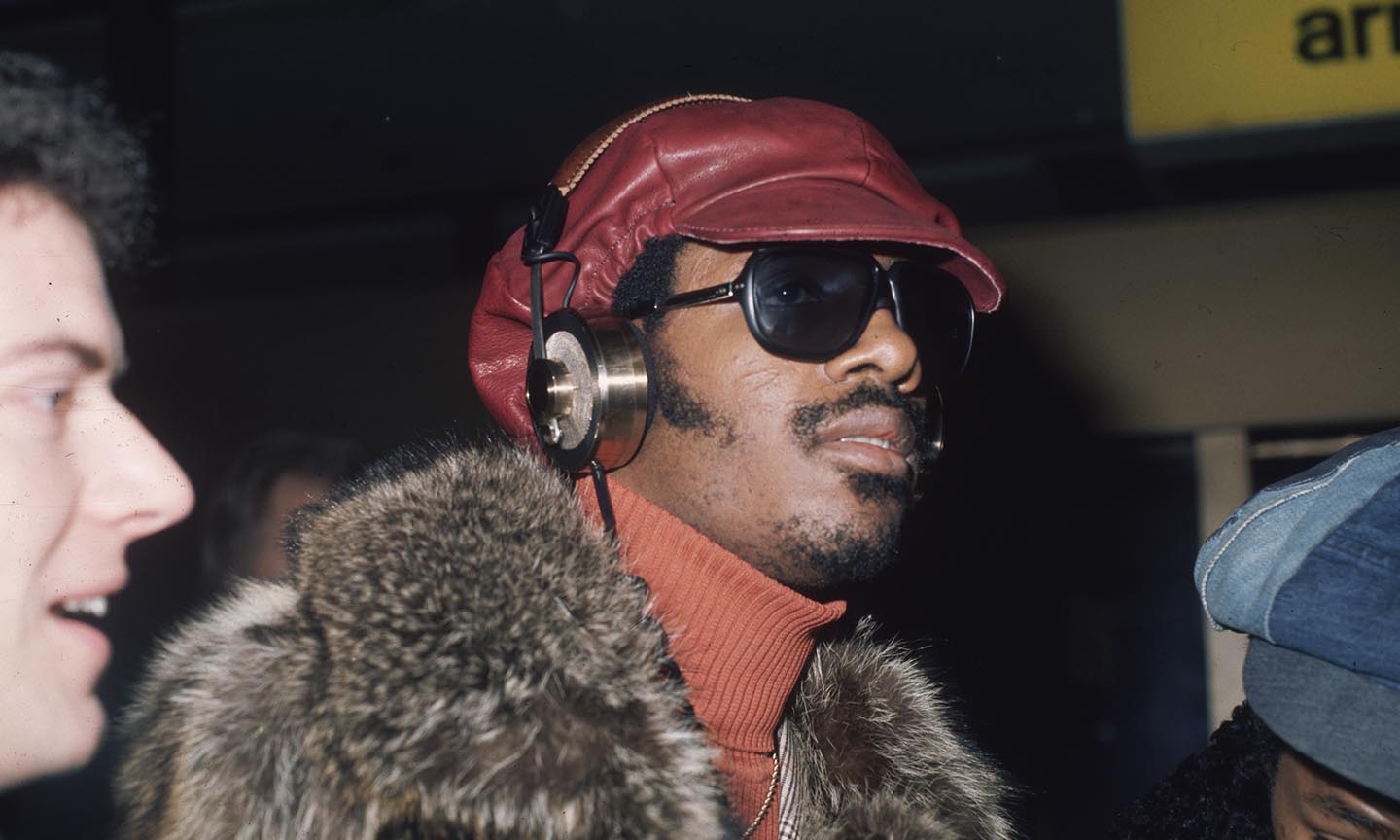

Stevie Wonder’s five-album run throughout the early and mid-’70s is considered one of the best runs in recorded music history. This is such a rich period of history, for both Wonder’s musical and personal life as well as American history, that these fruitful years are the subject of a brand-new podcast, The Wonder of Stevie.

Narrated by New York Times critic Wesley Morris and produced by Higher Ground Audio, Pineapple Street Studios, the six-episode The Wonder of Stevie podcast explores each of Wonder’s five albums from his “classic” period, from 1972’s Music on My Mind to 1976’s Songs in the Key of Life, as well as Wonder’s life, tragedies, and triumphs from all the way back to childhood. The Wonder of Stevie also offers new perspectives on the two albums Wonder made after Songs in the Key of Life: 1979’s Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through “The Secret Life of Plants” and 1980’s Hotter than July. Interviewees include Barack and Michelle Obama, Dionne Warwick, Smokey Robinson, Babyface, George Clinton, Yolanda Adams, Jimmy Jam, Michaela Angela Davis, and Janelle Monae.

Here’s what we learned from listening to The Wonder of Stevie.

Order Stevie Wonder’s greatest hits compilation, The Definitive Collection, on vinyl here.

Wonder’s blindness came from being born early

Born in 1950 as Stevland Hardaway Judkins in Saginaw, Michigan, Wonder’s early birth resulted in a retinopathy of prematurity, which left him without sight. His mother, Lula Mae Hardaway, insisted that Stevie would not be treated differently than his four siblings. He and his family never referred to his blindness as a handicap.

Wonder was discovered by The Miracles’ Ronnie White while playing at church—and was quickly introduced to Motown’s founder, Berry Gordy

White was so impressed with Wonder’s abilities at such a young age that he arranged for him and his mom to come to Motown’s headquarters in Detroit to meet Gordy, who also was impressed with each new instrument the young Wonder picked up. The rest was history.

Gordy was able to sign Wonder to a four-year recording contract with the help of the Michigan Department of Labor

Being a minor at the time, Wonder was able to officially record and tour with Motown only after Gordy negotiated an agreement with the Department of Labor. Wonder’s mom represented him legally.

Wonder wanted his stage name to be his birth name

But the people at Motown were so awed by the young boy’s talents that instead of calling him Stevland Hardaway Judkins, they kept calling him Little Stevie Wonder. The latter soon became the name that stuck.

At first, Gordy tried to present Wonder as the new Ray Charles

An early Wonder album was even called Tribute to Uncle Ray. Both were without sight and incredibly musically talented, and Stevie was influenced by Ray, but they were from two different generations.

Motown began to take Wonder’s songwriting more seriously after “Uptight”

“Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” was the first of Wonder’s singles that he wrote, co-written with Motown songwriter Sylvia Moy. It was a success, going to No. 3 on the Hot 100, and proved that Wonder, now no longer “Little,” could write and perform his own songs.

When Wonder re-signed with Motown at age 21, he negotiated for his own publishing company

To break free from the Motown system, a newly adult Wonder demanded his publishing company, Black Bull, to own the publishing rights instead of Motown, with total artistic control over all his songs. He wanted autonomy, and he got it.

Wonder joining The Rolling Stones’ 1972 tour was vital in helping him expand his audience

“It’s unheard of for one demographic to step outside of their comfort zone and grab an entirely other demographic,” says Questlove. “White artists cater to their white crowd. And this is one of the ways that Stevie Wonder will start living up to the promise of creative genius that can be commercially viable.”

Talking Book is the rare Wonder album cover in which he isn’t wearing any sunglasses

Talking Book marked an important transition moment for Wonder, who was now reaching massive audiences with a new sound that transcended his previous works. “Part of what he’s communicating is that he’s looking to transcend these categories that we are somehow being locked into,” says Barack Obama. “Part of what he’s saying is, I’m gonna upend or scramble a bunch of these hierarchies.”

Talking Book also comes with a braille inscription with a special message from Wonder

It reads as the following: “Here is my music. It is all I have to tell you how I feel. Know that your love keeps my love strong.”

Wonder wrote “Tell Me Something Good” and gave it to Chaka Khan

Wonder presented a few songs to Khan, most of which she was not into. According to Khan, Wonder finally asked her what her sign was and quickly presented what became the smash hit, “Tell Me Something Good.”

“Living For The City” was partially Wonder’s response to the killing of Clifford Glover

On April 28, 1973, 10-year-old Glover was shot by a police officer while walking with his stepfather in Queens, New York, wrongly believing that the young boy was threatening him with a gun. The shooting made national news, shocked and angered a country in the middle of horrible racial tension and Wonder even sang at Glover’s funeral. Months later, Innervisions was released.

After a car accident placed him in a coma, Wonder felt like a completely new man

After a near-fatal accident in 1973, Wonder reevaluated his relationship with spirituality and God. This change in direction and focus can be heard especially in his next album, Fulfillingness’ First Finale.

Songs in the Key of Life was the third album, and the first by an American artist, to ever debut at No. 1 on the Billboard Pop Album charts

Released in 1976, Wonder’s most epic release of his classic era was a critical and commercial hit in every sense. It would spend 13 weeks at the top of the Billboard 200 and continues to be called by many fans to be his best album.

Order Stevie Wonder’s greatest hits compilation, The Definitive Collection, on vinyl here.