The story of the recording studio can roughly be divided into two time periods: before and after the 60s. As to exactly where the year dot is, opinion is divided. But during a few phenomenally eventful years between 1965 and 1967, the studio changed from being simply a place of work for musicians, engineers, and music producers, to becoming a creative hub.

Check out our playlist featuring some of the great producers included in this article.

In essence, by the Summer Of Love, the studio had itself become a musical instrument, part of the creative process, something to be experimented with, constantly re-evaluated. Nothing really changed in the studio itself – sure, new equipment continued to evolve, but the walls and ceiling, cables and screens, and even the general principle of recording through a multi-track desk onto tape, remained the same. What happened was a revolution in the head. The role of the music producer flipped inside out. As if a butterfly from a cocoon, the producer changed from a schoolmasterly overseer of his domain to a conduit, through whom sonic textures could be painted, as though they were, as Brian Eno put it, “painting with music.”

But how did this transformation come about? What exactly had record producers been doing up to this point, and what effect did this revolution have on pop music? To answer these questions, it’s worth going back to the very beginning.

Early sound recording

It was an American inventor, Thomas Alva Edison, who first devised a machine to record and play sound, in 1877. As he later recalled, his invention came about, as is so often the case, quite by accident. “I was singing to the mouthpiece of a telephone when the vibrations of the wire sent the fine steel point into my finger. That set me thinking. If I could record the actions of the point, and then send that point over the same surface afterwards, I saw no reason why the thing would not talk.” He set to work.

By speaking loudly into a mouthpiece, the vibrations of his voice were carried through a diaphragm to a stylus, which indented a spinning disc of tin foil with small marks. This was the recording process. Playback was achieved by simply reversing the process – so the stylus, when placed on the spinning foil, picked up the vibrations created by the small marks and sent them back through its diaphragm to a loudspeaker. Simple, but so very effective.

In the early days of sound recording, the focus was on improving the audio quality. The aim was to achieve a recording so clear that the listener might close their eyes and imagine that the singer or musicians were performing live in their own living room. Fidelity was the watchword.

Early music producers

In first five or six decades of recorded music, the producer was, by and large, a company man. It was for him to oversee recording sessions, as well as to bring together the artist, musicians, arrangers, songwriters, and engineers. A publisher would visit and try to sell the producer a selection of songs. Once the producer had his song, he would match it to an artist, book a studio session, an arranger to score the music, and musicians to play it. Engineers would position microphones to find the optimum positions. The producer ensured the session ran to time and budget – a good producer ran a tight ship, finishing a day’s work with two or three singles completed.

Before the introduction, in 1949, of sound-on-sound tape, records were often cut straight to disc, cutting the disc in real-time while the musicians played. A collapsed performance or poor delivery meant starting again, so it was vital that the producer had everyone well drilled and primed to deliver the performance of their lives – much like the manager of a football team, giving a rousing talk in the dressing room before sending his players out onto the field. But all this was set to change, as another American was set to launch the second revolution in recording music.

Les Paul and multi-tracking

Lester Polfus, from Waukesha, Wisconsin, had already made a name for himself as a musician, writing advertising jingles or playing guitar for the likes of Bing Crosby and Nat King Cole. Yet it was under the moniker Les Paul – along with wife Mary Ford – that he’d scored a number of hits on Capital Records, with whom he’d signed in 1947. Unlike pretty much everyone else, however, he didn’t record in one of the label’s in-house studios, but crafted hits in his garage at home.

Paul was a man of great curiosity, always trying to figure out how things worked, and it was this inquisitiveness that led him to invent layered recording. His prototype for multi-tracking, as it would become known, involved him recording a number of guitar tracks onto the same acetate disc, one after the other. “I had two disc machines,” he recalled, “and I’d send each track back and forth. I’d lay down the first part on one machine, the next part on another, and keep multiplying them.”

Paul soon translated his technique to a tape recorder, after Bing Crosby brought him a brand-new Ampex 300 series machine. But Paul, as ever, wasn’t content to simply use the machine as designed. He believed that, by adding an extra head to the machine, he could record over and over, layering sounds on top of one another on the same piece of tape. “And lo and behold, it worked!” he declared. Some considered what Paul did to be cheating – after all, this wasn’t the aim of the game, this wasn’t fidelity – but the hits flowed, and before long, other music producers were picking up on Paul’s novelty trick to see what sounds could be created.

Sam Phillips

Not everyone was looking to multi-tracking. On January 3, 1950, a young talent scout, DJ, and engineer from Alabama opened the Memphis Recording Service on Union Avenue in Memphis, Tennessee. Sam Phillips opened his doors to amateur singers, recording them and then trying to sell the tapes to major record labels.

He was soon attracting the likes of BB King and Howlin’ Wolf. A fan of the blues, Phillips created a sound in his small studio that suited the burgeoning new styles that would become rock’n’roll and rhythm’n’blues. In March 1951, he recorded Jackie Brenston And His Delta Cats, led by Ike Turner, and their song “Rocket 88,” which is commonly regarded as the first rock’n’roll record. In 1952, Phillips launched his own label, Sun Records, and would go on to discover Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash, among many others. As well as knowing where to place the mic, and how to create the sound he craved by pushing the acoustics of his room, Phillips knew how to get his artists to look deep inside themselves to give the performance of their lives.

Joe Meek

On the other side of the Atlantic, meanwhile, Joe Meek, an electronics enthusiast from rural Gloucestershire, had left his job at the Midlands Electricity Board to become an audio engineer. His experiments in sound quickly bore fruit, with his compression and sound modification on Humphrey Lyttleton’s “Bad Penny Blues” scoring a hit. He founded his first label in 1960, and took up residence at 304 Holloway Road, London, occupying three floors above a shop. A bizarre individual, Meek’s talents were undoubted, and his recording of “Telstar,” credited to The Tornadoes, became one of the first UK singles to top the US chart, as well as hitting No.1 in the UK. Its otherworldly sound was a reflection of Meek’s growing obsession with the afterlife, which saw him attempt to record the late Buddy Holly from “the other side.”

Phil Spector

Back in the States, a young singer, songwriter and musician was turning his hand to record production. Having scored a hit with “To Know Him Is To Love Him” as one of the Teddy Bears, Phil Spector had begun working with songwriting legends Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. He made a number of minor hits as a producer while he honed his craft.

Through the early 60s, he began to turn those minors to majors, his first number one coming courtesy of The Crystals’ “He’s A Rebel,” which demonstrated his skill in building a symphonic sound in the studio by doubling up on many instruments. Spector felt that putting two or three bassists, drummers, keyboardists and guitarists would have the effect of layering sound, in much the same way that Les Paul used multi-tracking techniques. Spector’s “Be My Baby,” performed by The Ronettes, remains one of the all-time great 7” singles, and the producer seemed for a long while to have the golden touch. As the decade wore on, he built monumental, symphonic pop hits for Ike & Tina Turner (“River Deep – Mountain High”) and The Righteous Brothers (“You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling,” “Unchained Melody”) before hooking up with The Beatles to produce their Let It Be album.

Brian Wilson, musician and producer

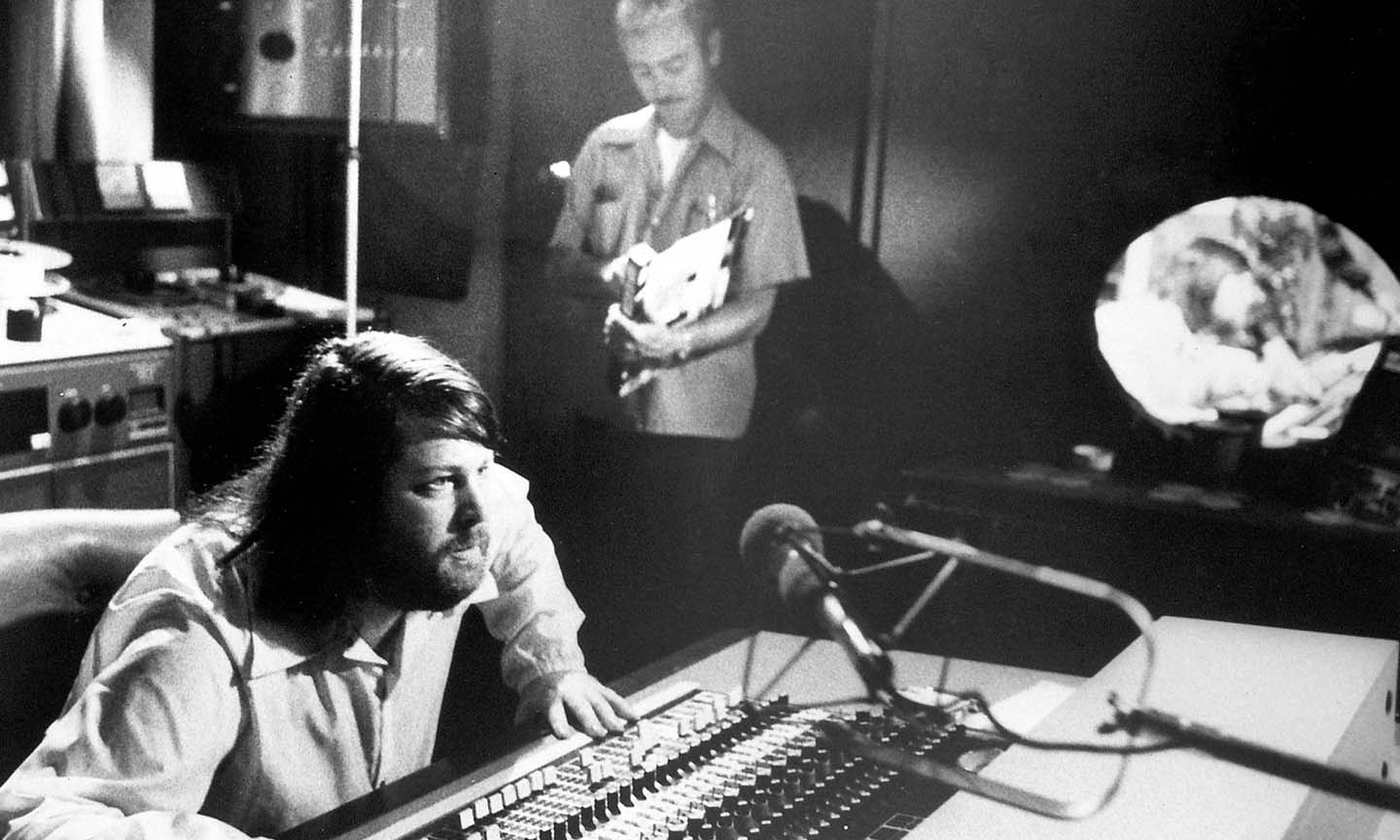

But it was Spector’s famous “Wall Of Sound” that made him such an influential music producer, and the leader of California’s Beach Boys was his biggest fan. Until now, it was almost unheard of for an artist to produce his own records, but that’s exactly what Brian Wilson began to do when, around 1964, he chose to leave the touring band, preferring to stay at home in Los Angeles and devote all his attention to the studio.

Wilson initially looked to emulate his hero, Spector, whose “Be My Baby” would become an obsession for the young Californian, but he soon found his feet, commanding many of Los Angeles’ finest musicians. Known today as The Wrecking Crew, these session musicians were used to working with only the best. But it was Wilson who pushed them furthest and hardest, challenging them to keep up with the increasingly complex music he was conjuring in his mind.

Layer upon layer of the brightest sounds combined to create simple-sounding pop music bleached by the sun and kissed by the stars, moving the band quickly from the Chuck Berry-esque rock’n’roll of “Surfin’ Safari” and “Fun, Fun, Fun” to the likes of “California Girls,” which combined imaginative instrumentation with The Beach Boys’ trademark harmonies, layered to create a dreamlike crescendo. But it was the song’s orchestral prelude that really caught the ear. Beginning to perfect the way he was combining sounds, Wilson used the studio to try and match his ambition of writing what he later called “a teenage symphony to God.”

The Beach Boys’ 1966 Pet Sounds album has been voted the greatest album of all time. Seemingly endless sessions in studios all over LA were used to build a beautiful album characterized by innovative sound matches, effects, and multi-tracked harmonies, with the Boys ultimately sounding not unlike a heavenly choir. But Wilson couldn’t be satisfied, and immediately set to work on a song that would trump even this. For “Good Vibrations,” he recorded the song in modular form, using one studio for the sound it gave to vocals, another for how he could capture percussion, and so on. When most pop records were still being made in a day, Wilson used a reported 90 hours of tape in building his masterpiece. The equivalent of around half a million dollars today was spent in his search for perfection. Even 50 years later, very few recordings have been as pioneering, imaginative, and glorious as the eventual single, which topped charts around the world.

But Brian Wilson always had one eye looking over his shoulder, towards London’s Abbey Road studios, where George Martin and The Beatles were fast turning the whole record-making process on its head.

The production of George Martin and The Beatles

George Martin had been with EMI since 1950. The young music producer found great satisfaction and enjoyment in the experiments in sounds inspired by the comedy and novelty records he made with Flanders And Swann, Bernard Cribbins, Dudley Moore and, in particular, The Goons.

By 1962, however, he was under pressure to find a hit pop act to add to his Parlophone roster. He duly signed The Beatles, completing their first album in a single day – aiming simply to capture the sound the group made. Fidelity, once again. But by 1965, the band had begun to make music that they couldn’t accurately reproduce live. For the instrumental break on Rubber Soul’s “In My Life,” for example, at John Lennon’s request, Martin wrote a Bach-inspired piano solo, but found he couldn’t play it fast enough. So they simply slowed the tape down, Martin played it at half speed, and then, when they played it back at normal speed, it sounded more like a harpsichord.

Martin’s founding in the sonic trickery of The Goons’ records put him in great stead to meet The Beatles’ increasing demands to make their records sound “different.” Their experiments would gather pace over the next couple of years, with innovations such as backmasking – recording tape played backwards – first included in “Rain.” But it was on their next album, Revolver, that their revolution took hold. Backwards guitars on “Taxman” and “I’m Only Sleeping” were nothing compared to the unfamiliar sounds that starred on “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Rock rhythms were supplemented by Indian motifs and strange sounds that weren’t made by instruments but were created by snipped and processed tape loops, faded in and out during the mixing process. The mix became a performance itself, never to be recreated. By now, the Martin and The Beatles were using the studio as an instrument in itself.

On their next album, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, they took things even further, pushing Martin to create a fairground noise, or to build an impossible crescendo of sound and then have it crash to nothing. During these sessions, Martin and his charges developed so many innovative techniques and processes that the resultant LP forever changed the way records would be made.

By working as partners with their music producer, rather than under his instruction, The Beatles had once again changed the face of pop music, and from here on, musicians would dream primarily of what they could create in the studio, and not of the excitement of a live performance. As Martin commented at the time, “You can cut, you can edit, you can slow down or speed up your tape, you can put in backwards stuff. And this is the kind of thing you can do on recordings; obviously, you couldn’t possibly do it live because it is, in fact, making up music as you go along.”

The Beatles themselves, however, along with many British Invasion groups, were most likely to be found listening to records produced not by maverick artists taking control, or by experimenters, but by a series of hit-making production lines dotted across the United States.

Motown, Stax, and the rise of studios with a sound

Motown, founded in Detroit in 1959 by Berry Gordy, a local songwriter and record producer, would become perhaps the most successful music factory in pop history, churning out hit after hit by Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Diana Ross & The Supremes, Four Tops, The Temptations, Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, to name but a few. By maintaining a “house sound”, Gordy and his team of music producers developed a brand that saw Motown become more than just a label, but an entire genre of music of its own.

Similar production lines were found in Memphis, where hits by Otis Redding, Sam And Dave and Rufus Thomas made Stax Records a force to be reckoned with in Southern soul music. Unlike Motown, where the producer ran everything in an almost dictatorial fashion, at Stax the musicians themselves were encouraged to produce records, so the boundary between producer and musician was virtually non-existent.

Once a music producer got a successful sound out of his studio, people would flock to record there. In Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Rick Hall ran his FAME studios, where he had created such a uniquely desirable sound that attracted artists from all over the country, such as Etta James, Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett. Then there was Phil and Leonard Chess’ Chicago studio, which created the sound of blues beloved of Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley and Little Walter. In Nashville, Tennessee, producers such as Chet Atkins, Paul Cohen and Billy Sherrill made the sound of country music, while in Jamaica, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Coxsone Dodd and Duke Reid created the sounds that would become reggae.

Music production in the 70s

By the end of the 60s, technology was allowing for more and more tracks – the four-track console used by The Beatles to make Sgt Pepper’s was soon replaced by an eight-track, which in turn was usurped by 16- and then 24-track desks. Soon, the possibilities were endless. But by now, the artist was often replacing the producer, with many acts preferring to mastermind their own records. But removing this once-schoolmasterly figure often led to self-indulgence, and the 70s became known as much for how long records took to make, as they did for how great the records were. Fleetwood Mac took a year over their Rumours album, for example.

Meanwhile, Tom Scholz took things a step further again, when he produced the eponymous debut album by the band Boston. The reality was that there was no band. Boston was actually Scholz, recording the album in his own basement, playing most of the instruments himself, and then forming a group to reproduce the songs live.

By now, the divide between music producer and artist was becoming more and more blurred. As the 70s progressed, in rock music, bigger and more complex was the name of the game, with Queen’s remarkable “Bohemian Rhapsody” produced by Roy Thomas Baker in a manner not entirely dissimilar to the modular process favored by Brian Wilson on “Good Vibrations.” Jeff Lynne of Electric Light Orchestra aimed to update The Beatles’ sound (without the technical limitations that had faced the Fabs), while Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells pushed technology to its limits.

Hip-hop production

But while all this was happening in the world of rock, yet another revolution was taking place on the streets of New York City. Tough times were reflected in the music created by Kool DJ Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash. Hip-hop and rap music has its roots in the Caribbean, with mobile sound systems set up on the streets and being fronted by a new interpretation of the reggae tradition of “toasting”, or talking over the top of a looping rhythm track.

These groundbreaking artists further removed the need for an outside producer, as they produced their own music. Sampling other peoples’ records in order to create brand new sounds was, in many ways, a hi-tech version of British groups like Led Zeppelin copying the blues music they loved, but creating something new with it. Following the global smash that was The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rappers Delight,” which lifted heavily from Chic’s “Good Times,” the rap music explosion inspired some of the most innovative producers in music history, pioneering sampling technology to remove the limitations faced by live DJs.

Rick Rubin had enjoyed success producing LL Cool J before hooking up with Run-DMC. Rubin married Run-DMC with Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” to unite rock’n’roll with hip-hop, thus cementing the underground style in the mainstream consciousness. As Rubin put it: “It helped connect the dots for people to understand: ‘Oh I know this song, and here are these rappers doing and it sounds like a rap record, but it’s not so different than when Aerosmith did it and maybe I’m allowed to like this.’” (Rubin would later hone a very different production style and revitalize the career of Johnny Cash.) Hip-hop producers like Dr Dre, Puff Daddy and The Bomb Squad, who produced Public Enemy, furthered hip-hop’s growth, making it the biggest sound in the world.

The rise of the star music producers

Once hip-hop had become ubiquitous, not only had the differences between artist and music producer dissolved, but so had the assumption that music remain bound by genre. By the 90s and beyond, nothing was off the table. For the biggest acts in the world, the key to continued success was hooking up with the most forward-thinking producers. Pop star Madonna wanted hip-hop innovator Timbaland to produce her, while Mariah Carey similarly hooked up with The Neptunes. Danger Mouse has worked with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Adele and Gorillaz, while Mark Ronson is in such demand that his services have been used by everyone from Amy Winehouse to Robbie Williams, Lady Gaga, and Paul McCartney.

Where once, the role of a producer was to represent the record company, to find an artist, combine them with a song and hope for hit, today, the music producer is in some cases as big as the artist, as big as the label, and has become – as they were at Motown – a hit factory of their own. Yet despite the multi-billion-dollar music industry behind them, today’s producers are still merely emulating Edison in his workshop, or Les Paul in his basement: trying things out, pushing the boundaries, hoping to create something new.

As George Martin said, “When I first came into the record business, the ideal for any recording engineer in the studio was to make the most lifelike sounds he could possibly do, to make a photograph that was absolutely accurate. Well, the studio changed all that… because instead of taking a great photograph, you could start painting a picture. By overdubbing, by different kind of speeds… you are painting with sound.”