Four years after a military coup left Brazil in the hands of a dictatorship that lasted two decades, things were looking decidedly grim for the country. In March 1968, Brazilian student Edson Luís de Lima Souto was murdered while protesting against food prices in Rio de Janeiro’s Calabouço restaurant; as the military police stormed the eatery, de Lima Souto was fatally shot in the chest. By December that year, the AI-5 (Institutional Act Number Five) had been introduced, essentially removing most of the Brazilian population’s basic human rights.

Listen to Os Mutantes on Apple Music and Spotify.

Amid such oppressive conditions, a rebellious faction found room to flourish. However, far from being guerrilla warriors, the Tropicália movement was a loose collection of artists, poets, and musicians, the most visible of which – ringleaders Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, along with pioneering three-piece Os Mutantes – left a body of work that still resounds today.

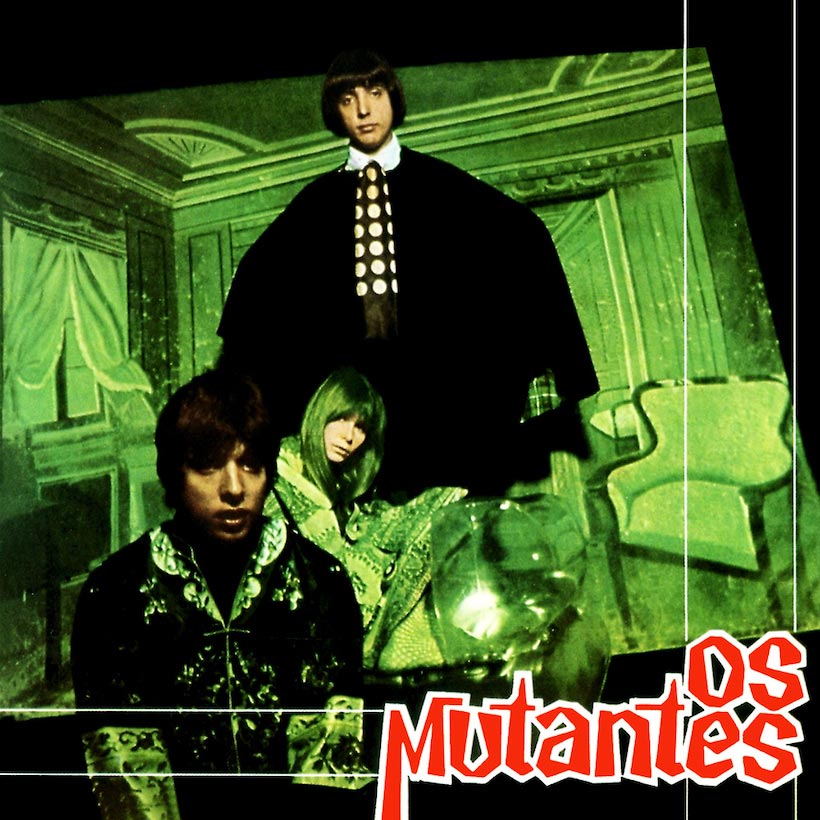

Gil and Veloso lit the touch paper when they masterminded Tropicália Ou Panis Et Circenses, a Beatles-indebted various-artists collection that, released in July 1968, featured the cream of the Tropicália artists, including Gal Costa and Tom Zé. Among them, too, was Os Mutantes – brothers Sérgio Dias and Arnaldo Dias Baptista, along with Rita Lee – who’d already gained notoriety in their homeland thanks to their televised appearance as backing band for Gilberto Gil at the 1967 TV Record festival, held in São Paulo. Beamed into the nation’s homes, if the group’s Beatle haircuts hadn’t given it away, their unashamed embrace of Western rock music was loud and clear: this was a cultural takeover. Traditional Brazilian music was no longer sacrosanct.

Os Mutantes’ contribution to the Tropicália album, “Ou Panis Et Circenses” (“Bread And Circus”), penned by Gil and Veloso, also opened their self-titled debut, released in June 1968. A suitably carnivalesque collision of trumpet fanfares, changing time signatures and what sounds at one point like scattered cutlery, it contains more ideas in one song than many bands have in a lifetime. But then, if The Beatles could do it, why couldn’t Os Mutantes? Political freedom may have remained some way off, but at least musical freedom was within reach.

Mixing and matching styles and influences with scant concern for heritage, Os Mutantes were essentially rebellious punks in the late 60s Brazil. “Bat Macumba” was a joyously riotous blend of samba drumming, funky bass, and proto-Eno sound effects (if they weren’t idiosyncratic enough, Os Mutantes’ had a nice line in homemade instruments); even when they hit a bossa nova groove, as on “Adeus Maria Fulô,” they prefaced it with a haunting intro that owed more to musique concrète than anything else traditionally associated with Brazilian music.

Elsewhere, their cultural grab-bag included “Senhor F,” which came across as a Portuguese-speaking Beatles in all their pomp; a cover of The Mamas And The Papas’ “Once Was A Time I Thought” (translated and renamed “Tempo No Tempo”); and, sticking to the original French, a cover of Françoise Hardy’s “Le Premier Bonheur Du Jour,” with a suitably dreamy vocal by Rita Lee. Arguably their most lasting impact was, however, courtesy of “A Minha Menina,” a Tropicália/psych classic later covered by Bees on their 2002 debut album, Sunshine Hit Me, and whose influence can be felt in one of Beck’s overt nods to the Tropicália movement, “Deadweight.” (Indeed, in 2010, Beck invited Sergio Dias to make up an ad hoc group of musicians to perform INXS’s Kick album in its entirety, proving that Dias has lost none of his disregard for cultural boundaries.)

Arguably the apogee of all things Tropicália, Os Mutantes remains a fascinating example of what happens when you throw out the rulebook.