In 1969, The Who released an album that would irrevocably change their fortunes. Their rock opera, Tommy, was a huge success in their native England, but even more so in America, where it was hailed a triumph of the surging rock scene.

Tommy was such an imposing milestone that Pete Townshend, The Who’s chief songwriter, faced great difficulty when charged with creating a follow-up. As a concept album, Tommy’s narrative about a boy, rendered deaf, dumb, and blind after violent trauma and abuse, who grows up to be a pinball-playing messianic leader, was complex, but accessible enough for it to be adapted into a movie (by Ken Russell, in 1975). The plot for Townshend’s next act, however, would prove almost unfathomable, even to those closest to him.

Listen to The Who’s “Behind Blue Eyes” as part of the new edition of Who’s Next I Life House now.

Tommy’s inspiration

Tommy’s inability to communicate yet command a devoted following was a reference to the teachings of Townshend’s spiritual mentor, Meher Baba, an Indian guru who taught compassion and divinity despite taking a vow of silence in 1925 that lasted until his death in 1969.

The guitarist had been introduced to Meher Baba’s texts in 1967, and connected with the master’s belief that life was an illusion, and only by transcending its false pretenses would one become closer to God. Baba’s guidance was still on Townshend’s mind in 1970 as he envisioned the outline of a new story that drew on the guru’s directions to human betterment.

Life House

The guitarist began to develop an elaborate parable he called Life House, a futuristic dystopian fantasy in which an enslaved people – who’ve never experienced rock ‘n’ roll – are ultimately liberated by the communal connectivity of music.

It was prompted by the beliefs of Indian musicologist and Sufi pioneer Inayat Khan, who called music “the nearest way to God,” and submitted that the universe was united by a single harmony. In this, he reasoned, the human spirit was connected to and affected by the vibrations of sound. Townshend, aware of the power he wielded over his fans while on stage, couldn’t help but relate.

Composing the music

The trappings of technology are a running theme in Life House, and so it was that Townshend turned to the latest in electronic instruments to best realize his intricate notions of transcending artificiality.

Always a keen sonic adventurer, Townshend was an admirer of the American minimalist composer, Terry Riley, whose progressive and improvisatory techniques – which included the innovative use of tape loops and droning explorations of single chords – greatly motivated his own electronic experiments.

Examining the possibilities of creating a chord from a number of different sources, Townshend believed that he could feed a person’s biographical information into a synthesizer linked to a computer to produce a unique aural portrait – “like translating a person into music,” he would explain. Furthermore, by multiplying the number of inputs, one could generate a synergetic compound that resonated with the harmony of the universe.

Armed in his home studio with a Lowrey Berkshire Deluxe TBO-1 organ, Townshend decided to concoct a pattern that was determined by the input of Meher Baba. The result, made with the instrument’s ‘Marimba Repeat’ feature, was a pulsing and persistent rhythm that bore more than a passing resemblance to the work of Terry Riley. He would name it after his two muses: “Baba O’Riley.”

The song’s lyrics

The lyrics of what would become “Baba O’Riley” served as an introduction to the plot’s central characters. In a polluted world oppressed by an autocratic government that administers real life experiences through the medium of technology, Ray and his wife, Sally, are living a self-sustaining existence “out here in the fields” on a remote farm in Scotland.

Hearing news of Life House, a live music event that promised to set society free with its stimulating vibrations, they set off to reach it, and their daughter, Mary, who had already begun her own pilgrimage. “Sally, take my hand,” Ray urges, “we’ll travel south ’cross land,” and off they venture to be with “the happy ones.”

Their voyage takes them through barren wilds, a middle England ravaged by pollution. Hordes of young castaways can be seen on their own journeys to Life House. In imagining these forsaken badlands, Townshend recalled the debris left behind by the audience of The Who’s gig at the 1969 Isle Of Wight Festival, and “the absolute desolation of teenagers at Woodstock, where audience members were strung out on acid and 20 people had brain damage.” He called this bleak landscape a “teenage wasteland.”

Recording the song

After terminating initial sessions in New York, where they’d attempted to record the Life House songs with manager/producer Kit Lambert, The Who decamped back to London to work instead with famed producer Glyn Johns – first at Mick Jagger’s Stargroves country house, and then to Olympic Studios in Barnes. It was here in May 1971 that Glyn Johns transferred Townshend’s synthesizer demo to 16-track, turning it into the rhythm track that the band would record to.

With the synth line playing back through their headphones, The Who performed the song live in the studio. (They would produce a 30-minute version of the song, but it was a five-minute edit that made it onto Who’s Next.) An extended arpeggiated intro gives way to Townshend’s strident piano chords, before the ever-boisterous drummer Keith Moon joins in, all rolling toms and shimmering cymbal crashes. Just as bassist John Entwistle lays down his powerful, anchoring root notes, in comes singer Roger Daltrey, his mighty delivery a dramatic replication of the protagonist’s desperate plight.

It’s almost two minutes before you hear Townshend’s guitar: a thundering cascade of power chords that echo the very foundations of savage, raw rock ‘n’ roll. They lead to a moment of respite, wherein Townshend’s comforting refrain – “Don’t cry, don’t raise your eye / It’s only teenage wasteland” – becomes the song’s emotional core, before Moon leads the ruckus back in with a thunderous fill.

The rollicking, double-time outro part had already been recorded, when Dave Arbus was invited in to add violin. “That was Keith Moon’s idea,” remembered Glyn Johns. The drummer had visited the progressive rock group East Of Eden in the studio next door, and thought their violinist would make a perfect addition. “And he had to speed up with Keith, of course, so that was quite difficult to do. He walked it, really. It was really good.”

An enlivening finishing touch, Arbus’ violin became the ‘O’ in the song’s title – because, as Townshend explained, “it sounded a bit Irish at the end.“

Abandoning Life House

Townshend had developed plans for Life House as a play and a movie, but its complicated storyline could not even be fully grasped by his bandmates. His creative investment in the project was so intense that, faced with crushing impediments, he suffered a breakdown. “It hurt when I realized it was all a crazy idea,” he’d say. “The self-control required to prevent my total nervous disintegration was absolutely unbelievable.”

It was decided that instead of the double album the group had planned for the Life House soundtrack, they should compile its strongest songs into a single album format, which is when they began working with Glyn Johns.

Life House was always ambitious. Its subject matter was astonishingly ahead of its time: in it, Townshend foretold the coming of the Internet and virtual reality, and warned of climate change and pandemic-style lockdowns. It was too formidable an undertaking in 1970, but Townshend was undeterred, and continued to return to it, until finally in 1999, it was broadcast as a play on BBC Radio 3, followed a year later by Life House Chronicles, an exhaustive box-set that marked the project’s completion.

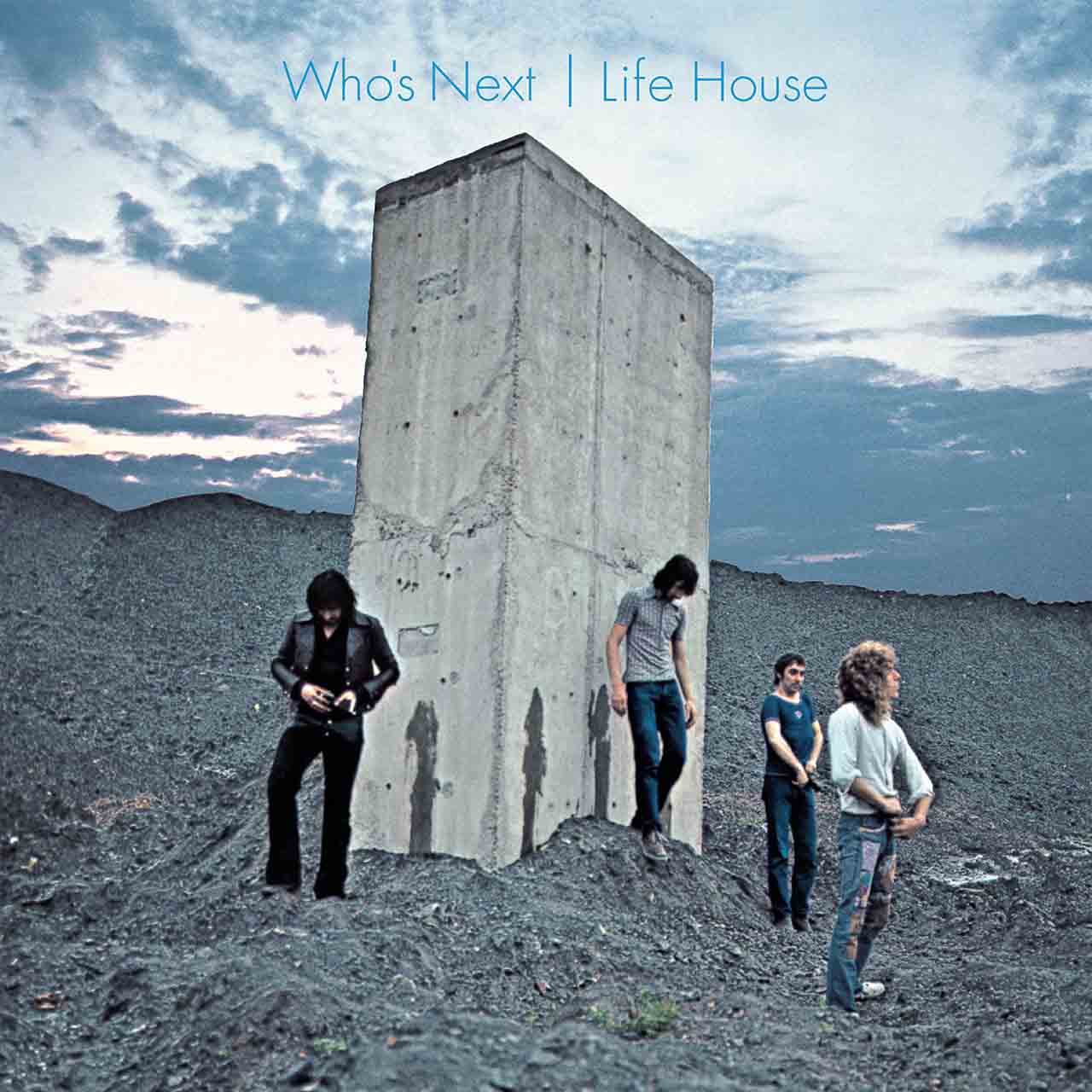

The releases

Who’s Next was released in August 1971. Glyn Johns had expertly captured The Who’s live dynamics, and as a result, the album sounded massive. Its impact was immediately felt, reaching Number One in the UK. The songs were undiminished by their extraction from Life House’s narrative, and made for a cohesive and forceful masterpiece that critics deemed outstanding.

“I was delighted with it,” Townshend said of Who’s Next. “It felt like The Who’s first proper album. It felt uncomplicated and simple and I just didn’t care that the story had been lost. I was just relieved to have made anything.”

“Baba O’Riley” was never released as a single in the US or UK – and only to moderate success in half a dozen European countries – but its stature as an aggressive, strutting anthem was widely and readily acknowledged, and it was a potent choice of album cut for radio DJs, fast becoming a subversive classic of the decade.

The legacy

With its towering and defiant final cries of “Teenage wasteland,” “Baba O’Riley” has long been celebrated as a hymn to self-assertion, one that teeters on the fine line between disobedience and full-on hostility. A soundtrack for revolution.

It is closely associated with a sense of mettle, and as such has become a cultural touchstone for film and TV makers wishing to reflect a fighting spirit. Spike Lee, for example, used it to great effect in his 1999 crime thriller Summer Of Sam, but it is perhaps best known as the theme song for the forensic cop show CSI: NY.

To The Who, it is their sixth most-played song on stage, and usually their climactic finale – they most famously unleashed its fury at the Concert For New York City in 2011, and the closing ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics. To the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, it is one of the “500 Songs That Shaped Rock ‘N’ Roll.” To Roger Daltrey, however, it’s also a prescient warning of technology’s firm grip on our collective conscience.

“[It] speaks to generation after generation,” the singer said. “Life is not looking down at screens, it is looking up. We are heading for catastrophe with the addiction that is going on in the younger generation. Your life will disappear if you are not careful. You are being controlled, and that is terrible.”

Listen to The Who’s “Behind Blue Eyes” as part of the new edition of Who’s Next I Life House now.