It’s the first snowfall of the season in New York City, and NME is tucked into a warm balcony at Brooklyn Paramount with the rising folk artist Mon Rovîa, watching Natasha Bedingfield perform ‘Unwritten’. As the Liberia-born, Tennessee-raised songwriter tells us later, he’s still familiarising himself with the secular pop hits most of his contemporaries know by heart. But right now, he seems to be immersed in the moment, echoing the choruses and laughing with his bandmates, his phone pointed towards the stage.

The renovated theatre – once a jazz venue where legendary Black artists like Ella Fitzgerald, Miles Davis and Duke Ellington played – is the perfect backdrop for the night’s Children In Conflict charity event, where a mix of celebs and artists such as John Oliver, Common, Anthony Ramos, Bedingfield and Mon Rovîa are performing to raise funds for safe spaces, education and mental-health resources for children impacted by war. It’s a cause that’s acutely close to home for Mon Rovîa, who was born amid civil war in Liberia and rescued by missionaries from life as a child soldier. He punctuates his set with stories of his family and what he witnessed in the country he came from.

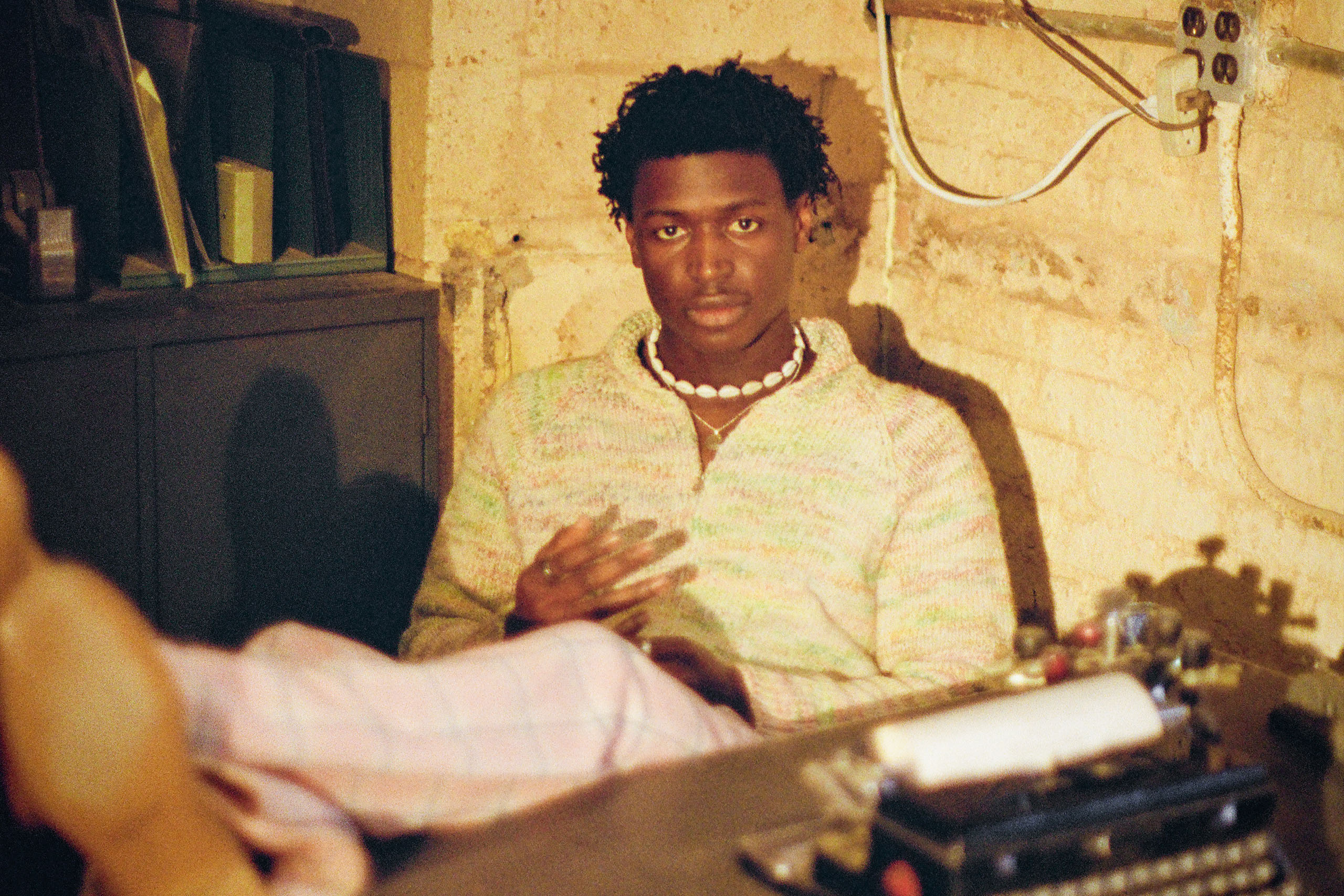

Mon Rovîa on The Cover of NME. Credit: Marisa Bazan for NME

“I chose some of our more conscious songs about the world and the things that are happening in it,” the roots artist, born Janjay Lowe, tells NME over coffee at a Williamsburg cafe the next day. ‘Heavy Foot’, an uplifting protest song that gently builds to a sing-along chorus on how the government can’t “keep us all down”, made the setlist, as did ‘Whose Face Am I’, about children in conflict who lose their families and “wonder what their history was [and] what their parents looked like”. There was also the slow-burning highlight ‘Bloodline’, a sonic amalgamation of his Appalachian upbringing under lyrics about his Liberian roots. It’s the title track of Lowe’s debut album, set to be released this Friday (January 9). “I had a lot of songs that play into [the night’s] overall theme,” he smiles.

For Mon Rovîa, sharing his stories on stages across the globe and at major festivals like Newport Folk Festival, Bonnaroo and Austin City Limits are “full circle moment[s]”. “I talked about it a little last night, how you wonder what the purpose of your life is when you come from those situations,” he says. “You’ve left so many people behind and other kids didn’t make it out. Sharing these [songs] keeps those people alive in my own way by always reminding us of how important it is to take care of the next person, to be present and aware of people’s suffering. That’s my goal. Maybe that’s why I was rescued,” he pauses, his eyes shifting down toward the table, hinting at the survivor’s guilt he mentions throughout our conversation, the “why” of his success and life path.

Credit: Marisa Bazan for NME

Adopted by a pastor and raised across the US but mostly in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Lowe’s journey has not only led him to a singular sound he calls “Afro Appalachia”, but has also allowed him to participate in reclaiming the under-documented history of African American folk music. “It was cool to learn about the instrument of the banjo coming from West Africa where I’m from, right there on that coast. It really fortified me.”

In reclaiming history and his lineage, empathy has emerged as a driving force in his work. His haunting song ‘Winter Wash 24’, for instance, is “about the situations in Congo and Palestine and the kids suffering in those places” – at once a plea for compassion and a reckoning with the “cognitive dissonance” of modern life in the West. Lowe believes empathy is why his songs have reached so many corners of the world. “If you have empathy, you understand the emotions. There’s instantly a bridge,” he says. “That’s been beautiful to see across the shows. Music really is a powerful thing, and the weight of it and the responsibility of it is something I keep in mind.”

“Music really is a powerful thing. The weight and responsibility of it is something I keep in mind”

That weight includes his desire to practice the folk tradition of archiving his past while honouring his present. It also means paying respect to the land, language and family he left when he moved from Liberia to the US with his adoptive parents at just five years old. Though he doesn’t recall much about his first years in Liberia, he does remember returning during the second civil war when he was around 10. “Going back to see my family, it was just terrible,” he says. “Like leaving trauma, then going back and being retraumatised.

“You remember the sounds of the gunfire. There are bodies, kids with AKs walking around the city – but you have to live normally. The city of Monrovia was taken over by these child soldiers,” he adds, noting the capital city he takes his stage name from. He shares a surreal memory of spending time with his brother, who, unlike him, didn’t escape being a child soldier. “We sat on this bench and we didn’t say much to each other,” he says slowly while shaking his head. “Both of us were crying, knowing that we shared this blood, but not really knowing each other at all. I always remember that image. And I haven’t seen him since.”

Credit: Marisa Bazan for NME

Writing the songs of ‘Bloodline’, Mon Rovîa had to interrogate how he came to be. He’s been candid about the story of his existence, sharing how his biological father was a soldier from Senegal, his mother a working woman. The idea that his birth did not originate in love had nagged at him, but what ultimately surfaced in the storytelling was his mother’s love and her desire to keep and protect him. “The truth is she gave birth to this kid, kept him, took care as much as she could,” he tells us. “That child then gets adopted and is taken to the States and through a myriad of different things, becomes this artist that shares his purpose with other people who have struggled. That’s where the story continues.”

Even as he tells stories of war, loss, and painful self-discovery, it doesn’t take long for a smile to brighten his face. “I wrapped myself [up] in being someone that was jovial,” he says when asked about his light demeanour and gift for storytelling. “A lot of my sadness, I kept hidden. My role in my family when I was adopted was to be that joyful person. But I think the storytelling really came from watching my dad. He’s an incredible speaker.”

“If you have empathy, you understand the emotions in the music. There’s instantly a bridge”

Throughout our conversation, he speaks in metaphors and analogies much like a minister, leaving each congregation – whether it’s a journalist at a coffee shop or a packed audience that knows every word he’s singing – with a message of hope. He shares a compelling answer when asked what he hopes people take away from his music: “I am a reflection of the people that love me. Not of the people who have scorned me or the people that have trespassed on my soul, but of those that have accepted me, that say I’m beautiful, that I’m smart, that there’s a reason I’m here.”

Though Mon Rovîa sounds at home in the genre, he didn’t start making folk music until 2022. Before that, he “dabbled” in sing-song rap, though it never really spoke to who he was. At the same time, growing up in a predominantly white and middle-class environment, he didn’t see many Black artists making folk music that resonated with him. “I wasn’t confident in myself,” he explains. “I thought I had to go the rap route to try to do anything with music. That’s why I was so lost for a while.” But he picked up the ukulele and began to emulate artists he first heard on a playlist his two foster brothers had, like Bon Iver and Vampire Weekend.

Credit: Marisa Bazan for NME

The songs he began to write chimed with his early escapism through writing poetry, the indie music he grew up listening to, and made sense with the backdrop of his current life and ancestry. The songs he’s writing now, like ‘Old Fort Steel Trail’, which is about a river he grew up beside and the idea of not “robbing yourself” by constantly reliving the past, embody his continued aim to explore the folk music born in the Appalachians – and to pay homage to the enslaved people whose creativity will always be foundational to that region’s history.

Mon Rovîa’s millions of followers across social media reflect how his authenticity has resonated with listeners, and his debut album represents his desire that others will also embrace who they are. “‘Bloodline’ is the journey through my own becoming, but my hope is that it can be a companion to [listeners] on their own journey of understanding who they are and what the world is,” he says.

“Life doesn’t just stop at the beginning of suffering. There’s always more after. The album goes through a process of seeing some hard things, hearing some hard stories, and coming into a person who is resilient in what the calling of their life really is. That’s my hope for everybody who listens to it. Life is short,” he concludes, “but made long through love.”

Mon Rovîa’s ‘Bloodline’ is out January 9 via Nettwerk.

Listen to Mon Rovîa’s exclusive playlist to accompany The Cover below on Spotify or on Apple Music here.

Words: Erica Campbell

Photography: Marisa Bazan

Styling: Dylan Wayne

Label: Nettwerk Music Group

Location: Brooklyn Optics

The post Mon Rovîa’s ‘Afro Appalachian’ folk songs are rooted in resilience and love appeared first on NME.