JTBC‘s Good Boy commences with a great premise: a group of former Olympic athletes turned cops. But what might have been a cringeworthy crime genre remake is actually far more self-reflective — this series is a character study of justice, masculinity, and the weight of past trauma.

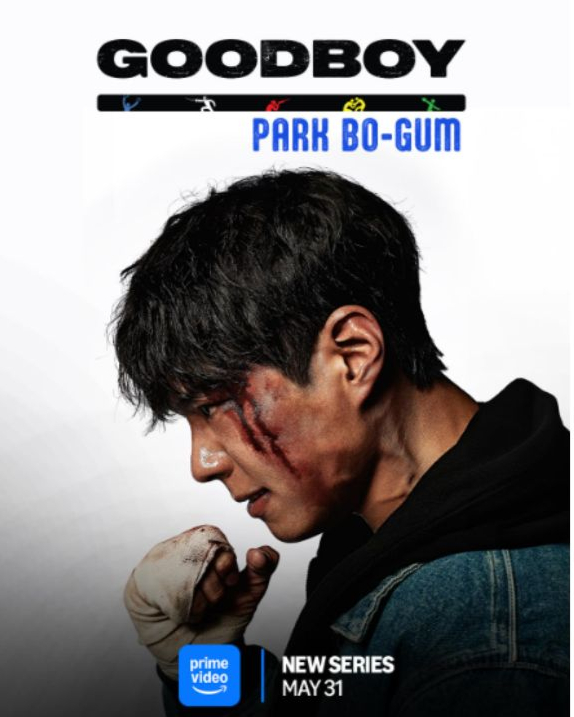

Holding center stage in the series is Yoon Dong-ju (Park Bo-gum), a national boxer who retired from the public eye after a targeted scandal that ruined his illustrious career. As a new rookie cop in a police squad formed to use physical ability over red tape, Dong-ju has an open, festering, burning sense of guilt. What drives him is more a need to relearn mastery of a life already usurped by ambition and publicity than redemption. When he declines to hit a low blow in a fight in episode 3, it’s not about honor; it’s about reacquiring the moral compass that fame once distorted. His journey is a case for how justice is redefined as personal responsibility instead of institutional retribution.

Park Bo-gum’s method acting is physically communicated to the audience. His physicality is conditioned and calculated, as years of sports conditioning have shaped him well to handle the grueling action sequences. Still, it’s the subtle moments between action that provide character depth. A moment of hesitation before entering a suspect’s house, or a hesitation before landing a punch, indicates Dong-ju’s biggest battle is not crime, but the self-restraint aspect of himself he’s attempting to shake.

His work with the team further develops the show’s rich exploration of masculinity. Episode 6 demonstrates how every retired athlete reacts (or doesn’t react) to his new role. The cast comprises retired weightlifter Ko Man-sik (Heo Sung-tae), who goes at policing with brawn, and ex-fencer Kim Jong-hyun (Lee Sang-yi), who uses precision and calculation to thwart criminals. At the same time, Tae Won‑seok shines as Shin Jae‑hong, who is a gentle discus throw medalist whose soft demeanor belies deep resolve and family devotion.

These characters are not flimsy. Each of them demonstrates tension between physicality and emotional openness in different forms. The bond that develops among them is not ambivalent but about vulnerability. The series calls these men to change not only as justice seekers but also as compassionate individuals, willing to listen, to make mistakes, and to come to each other’s rescue.

Contrasting this manly dynamic is Ji Han-na (Kim So-hyun), whose storyline heightens the emotional investment of the series. Han-na is a resourceful officer and the sole female team member, who is depicted as having a composed and confident persona. But there’s another, quieter storm bubbling under her surface as the burden of family pressure, in her case, comes from an overbearing mother who views her working career as a sidetrack from a predestined career path already mapped out for her. In episode 8 is the gut-check confrontation between the two, not in screaming over-the-top but in words well-practiced and, more significantly, in Han-na’s self-restraint on display. It is a scene full of everything she has not yet put into words.

Kim So-hyun shines in such moments of restraint. In episode 7, there is a close-up of Han-na’s face with her eyes intently set on a teammate, her posture stiff, which showcases a woman who is wrestling inwardly with loyalty and survival. Her conflict is not work-related or personal; it’s about occupying space in a world that tends to conflate strength with stoicism. Han-na is the emotional heart of the team, working discreetly behind their testosterone-fueled efforts, operating with sensitivity and compassion.

Even the show’s villain, Min Ju-yeong (Oh Jung-se), is no stock bad guy. He is portrayed as a smart thug with an iffy past — Ju-yeong physically and mentally tests the team’s limits. His sniping in episode 10’s standoff cut so deep because it revealed truths the characters would rather avoid about the violence into which they’ve been bred and the justice to which they purport to be devoted. Ju-yeong is never evil for evil’s sake. Instead, he’s an instigator who provokes the weakness of moral absolutism.

Visually, Good Boy’s director Shim Na-yeon knows when to go with action and when to back off. She balances kinetic sequences of events with carefully restrained contemplative framing. Specifically, a rooftop chase sequence in episode 4 is full of comic-book verve, while a rain-specked window in episode 9 is a mirror of Han-na’s loneliness. The soundtrack goes between pulse-racing energy and moments of lyrical introspection, reflecting the drama’s tonal duality.

What is interesting about Good Boy is how it takes a high-concept setup and uses it to tell an account of individuals compelled to rebuild themselves in the eyes of the public. Justice here is not dispensed by brawn or brains at the law, but by discovery, introspection, and public healing. All emotional subtlety projected by Dong-ju’s tortured hesitation and Han-na’s adamant silence, both project realism at its finest.

Good Boy is not just a sports-crime hybrid or a shallow cop drama; it’s a drama about what it actually means to begin anew and whether individuals built for competition can be taught to struggle for something deeper: connection, accountability, and self-respect, all while pursuing justice.

Images via JTBC and Prime Video.