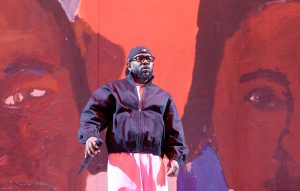

Getty Image/Merle Cooper

Welcome to another installment of Ask A Music Critic! And thanks to everyone who has sent me questions. Please keep them coming at steve.hyden@uproxx.com.

Here we are, not even (quite) in mid-December, and I feel like everybody has already posted their “Best Of 2024” music lists. Isn’t this weird? I know that websites have to chase clicks, but I feel like these lists run a bit too early. Why does this happen? Is it only about traffic? Or are there actual justifications for it? — Melissa from Akron, Ohio

Thank you, Melissa. It’s not often that I get an excuse to play my favorite game: Music Criticism Inside Baseball. My editor normally discourages me from putting on my Music Criticism Inside Baseball glove and throwing my hottest “nobody outside the industry gives a damn about any of this” pitches. But I think your observation (mild complaint?) is a common one. At least it’s one I have heard annually during this time of the year for as long as I have been in the business. I have even registered this low-stakes gripe myself (ironically!) from time to time. So, perhaps this is the proper occasion to finally clear the air.

I can actually think of two editorial justifications for running a year-end list during the first week of December rather than the third or fourth week. (Or — if you a true sicko when it comes to calendar purism — early January.) One is related to capitalism, and the other is borne from what I would call “seasonal philosophy.” But before we discuss this rationale, I want to address the concept of “chasing clicks.”

“Chasing clicks” has been used as a pejorative for as long as there has been online media. It is an epithet occasionally used by readers, and more often applied by self-hating media workers. “Chasing clicks” presupposes that websites are cravenly pursuing the attention of readers by any means necessary, and that this is done in the service of shadowy corporate overlords who greedily rub their hands together as the spoils roll in from all that disreputable online activity. You click on that “Best Of 2024” albums list, and off in the distance Scrooge McDuck and Logan Roy do dueling swan dives into a pile of money.

Oh, if only!

I’m going to make a confession: I chase clicks. That’s the business I’m in. The business is not “furthering the conversation.” It’s not overusing adjectives like “angular” or “shimmering.” It’s not even writing. I listen to music and write about it for fun and personal enrichment — it’s what I need to do — but I chase clicks for a living. Chasing clicks is the baseline task for anyone in my line of work. It is how, to quote the folk singer Todd Snider, I put food in my refrigerator. And let me tell you something: Chasing clicks is hard. Clicks are the most challenging game of all to hunt. You would have an easier time tracking and killing a Roosevelt elk than you would getting people to look for a damn second at your lil’ piece of insightful and clever music writing. But that’s the gig. I am Wile E. Coyote, and you are the Road Runner. If I don’t catch you, I get flattened by anvil. I know that. It’s what I signed up for.

What makes the hunt even more challenging is that if you have an ounce of integrity or shame, there are certain things you won’t do to make the hunt easier. Like, for instance, publishing something incredibly inflammatory, dishonest, or just plain stupid to get attention. The paradox of chasing clicks is that being good at your job — or simply trying not to be a clout-obsessed buffoon — might actually make you bad at your job. But sucking on purpose is an unacceptable compromise, as far as I’m concerned.

Here is an acceptable compromise: Running a year-end list in early December. That, to me, is not a big deal. Granted, sometimes someone like D’Angelo puts out a record like Black Messiah a week or so before Christmas, and you get burned a little. But given that 1) December is mostly bereft of new releases; 2) readers start to revert to holiday mode in mid-December; 3) list-reading fatigue is real; and 4) leaving a great album off a year-end list blows but it isn’t exactly the end of the world (nobody remembers what’s on these lists for more than 24 hours anyway). In the end, I think the cost/benefit analysis checks out.

Now, after all of that — the previous several paragraphs constitute a rigorous nine innings of Music Criticism Inside Baseball — what I’m about to say might come off as mere rationalization. And maybe it is! But I also believe these things to be true. So, take them as you wish.

There is a capitalistic reason for running year-end lists in early December. And it’s not just “chasing clicks,” though that’s clearly an additional capitalistic justification. But writing about these records three or so weeks before the holidays also helps to sell those records. I don’t have statistical data to support this, but I have reams of anecdotal evidence. People read about an album they don’t know about, they check it out, and they either buy it for a friend or family member or put it on their own holiday wish list. I know this. People have told me, many times, that this happens. And it probably would not happen as often if you ran these year-end lists at the literal end of the year, after the gift-giving season has concluded.

I don’t at all look at what I do as a “consumer guide.” But, at the same time, if something I write about an artist I admire can tangibly/financially benefit that artist, I feel good about that. So, there’s that.

There’s also the “seasonal philosophy” justification I mentioned earlier. And by that I mean this: Early December is when we start to look back at the previous 11 months. It’s a naturally reflective time. As the holidays approach, the outside world slows down and one’s thoughts turn inward. (I understand this argument doesn’t make as much sense in 2024, given the incoming president and news about at-large assassins getting apprehended at a neighborhood McDonald’s. But it’s still generally true.) It’s not just music — we do it with movies, politics, professional wins and losses, family drama, etc. But music seems like an especially attractive and effective way of marking time. In recent years, streaming platforms have capitalized on this by generating personal year-end lists for millions upon millions of consumers. It’s never been easier to track your own listening habits more thoroughly than even a professional critic does with his own. And when do these myopic inventories drop? Early December, of course.

Once the year ends, and we all find ourselves facing the blank slate that is January, this nostalgic impulse dissipates. It is no longer the time for looking back — it’s for imagining a version of yourself that exercises more and drinks booze less. Musically, you start to think about what’s on the horizon. Will this Ethel Cain record live up to her previous LP? Can I finally get into FKA twigs in 2025? Is Coachella going to flop in a few months?

I can’t wait. It’s all ahead of us. At least it will be then. But for now, we’re staring at the rearview mirror, and all that 2024 music is much closer than it might appear.