Hip-hop is not exactly renowned for its wallflowers, but there have been few stars as outrageously controversial as Eminem, aka Slim Shady. As prodigiously talented as he is confrontational, the Detroit rapper born Marshall Mathers on October 17, 1972, worked his way up from the underground to become the most successful hip-hop artist in the world. Among his many crowning achievements, in the 00s Eminem outsold every other musician in the US. And a recent, no-holds-barred, Donald Trump-blasting freestyle aired at the 2017 BET Hip-Hop Awards shows that he’s lost none of his capacity to spark outrage while refusing to temper his worldview.

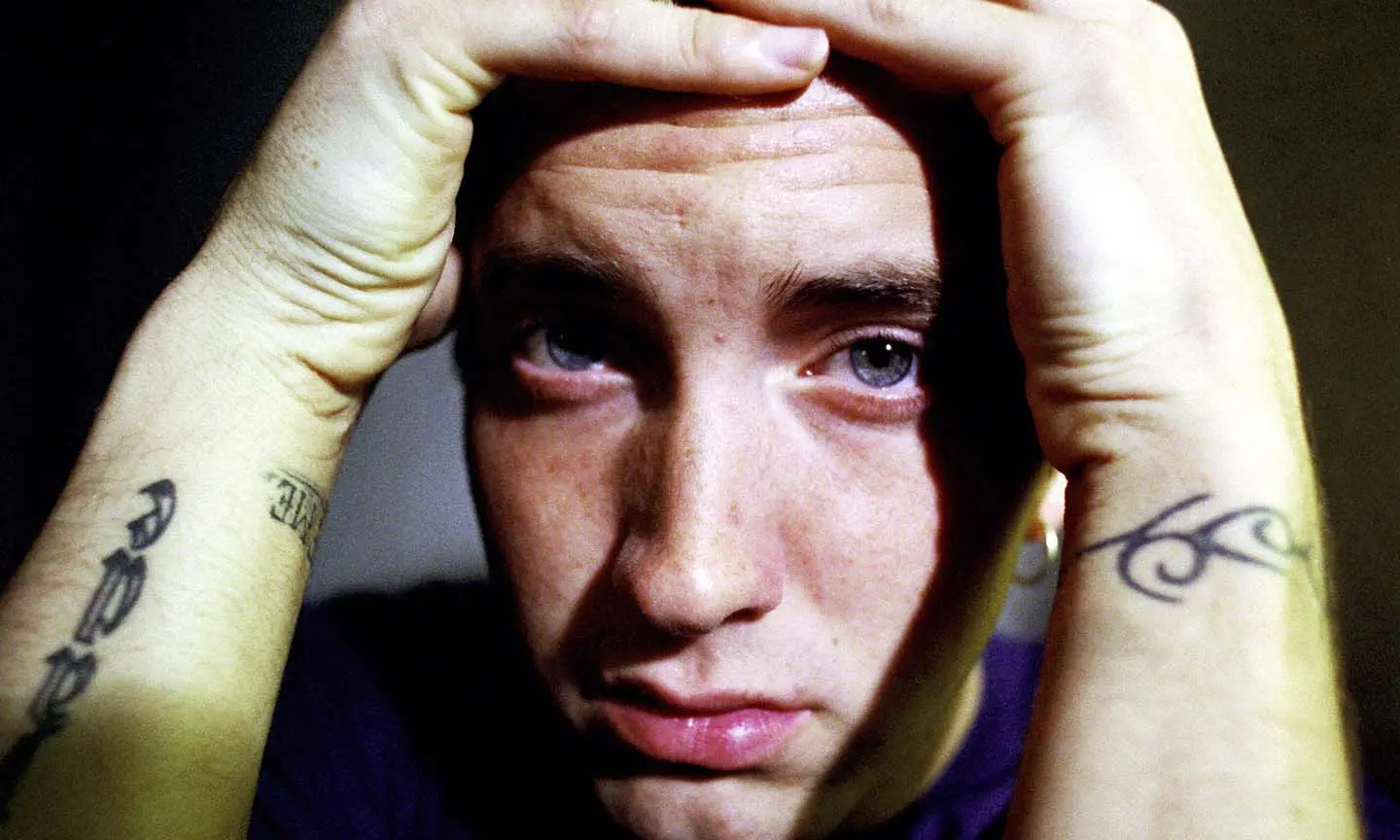

While it was Eminem’s dexterous, tongue-twisting rapping style that first got him noticed, the comic personas he invented turned him a global superstar. Taking on the guise of Slim Shady, he employed jet-black humor to delve deep into his troubled past – and to imagine the darkest of alternate futures. But who was the real Marshall Mathers and who was Slim Shady?

The act of playing detective and trying to separate fact from fiction is one of the great pleasures of trawling through Eminem’s music. At times his lyrics played out like a real-life soap opera, their emotional directness preempting modern hip-hop stars like Drake.

The real Slim Shady?

Many overlook Eminem’s little-known debut album, Infinite. Recorded in 1996, it found the nascent star still developing a distinctive style. However, it boasts a raft of complex rhymes and the verbal erudition of a man who had spent much of his youth absorbed in a dictionary. The subject matter was already highly personal, detailing the trials of living in one of Detroit’s poorest areas, and Eminem’s hopes for girlfriend Kim and their soon-to-be-born daughter, Hailie. But the album failed to have the desired impact, which, in turn, had a profound effect on the rapper. “After that record, every rhyme I wrote got angrier and angrier,” he told Rolling Stone magazine.

The genesis of this transformation came on a trip to the toilet, when Mathers concocted his Slim Shady alter-ego. “Boom, the name hit me, and right away I thought of all these words to rhyme with it,” he recalled. Bleaching his hair to add to the brattish image, Eminem now had a conduit through which he could vent both his cartoonish sense of humor and latent anger.

His sophomore album and major-label debut 1999’s The Slim Shady LP was issued through Interscope, and still has the capacity to shock. Under the aegis of his titular anti-hero, Eminem felt the freedom to expound on anything that took his fancy. The darkly comic tour de force single “My Name Is” introduced Slim Shady as a vengeful, ogre-ish, loose cannon. At once self-deprecating (“I ain’t had a woman in years/My palms too hairy to hide”), Eminem was also brutally personal in his attacks.

While much of the song’s cartoonish ultraviolence was clearly fictional, the line between truth and fiction was sometimes uncomfortably blurry. One line in particular, “99 percent of my life I was lied to/I just found out my mom does more dope than I do,” overstepped the mark as far as mother Debbie Mathers was concerned, and resulted in legal action. Elsewhere, On “Brain Damage,” Eminem recounts an alleged bullying episode at the hands of schoolmate D’Angelo Bailey – and another court case ensued.

Even the purely fictional had an unnervingly personal note. On “’97 Bonnie And Clyde,” a fantasy tale about a journey taken with his daughter to bury the wife he’d just murdered, the role of Eminem’s offspring is played chillingly by Hailie. However, The Slim Shady LP, which was partially produced by Dr Dre (and released via Interscope, home of Dre’s Aftermath imprint) was an unqualified success and turned Eminem into a global star.

Adding fuel to the fire

The Marshall Mathers LP followed swiftly in 2000 and found Eminem expanding on the dark humor of its predecessor. While that album found critics and public alike trying to separate fact from fiction, The Marshall Mathers LP blurred the boundaries yet further with its mix of razor-sharp humor and personal attacks. His mother came in for particular scorn on opener “Kill You”; his wife was verbally attacked on “Kim,” a prequel to “’97 Bonnie And Clyde” that details an imaginary argument that leads to murder. Shorn of the humor of much of Eminem’s output, it’s the most chilling song he’s ever made.

Yet, in Eminem’s oblique world, things are rarely what they seem. Interspersed between the stream-of-consciousness invective are moments of clarity: “Oh my god I love you”; “I don’t wanna go on/Living in this world without you.” Written at a time when the two had separated, “Kim” served as a method of both venting his anger and professing his love.

The blurring of truth and reality is addressed on closer “Criminal”’s spoken intro: “A lot of people think what I say on a record/I actually do in real life/Or if I say that I wanna kill somebody/That I’m actually gonna do it or that I believe in it/Well, shit, if you believe that, then I’ll kill you.” Adding further fuel to the fire, Eminem answered critics that had labeled his lyrics homophobic by performing the single “Stan” with Elton John at the 2001 Grammy Awards.

By now Eminem was one of the world’s biggest superstars. While The Marshall Mathers LP had set one-week sales records for a solo album, the media circus surrounding its creator had reached a fever pitch. 2002’s The Eminem Show found him taking a step back to examine the impact of his music and celebrity.

Opener “White America” tackles the government-led attempts at censorship based on his presumed bad influence on white suburban teenagers. Never afraid to tackle personal subjects, family relationships once more featured heavily; the continued fall-out of his very public row with his mother was dealt with in vitriolic fashion on “Cleaning Out My Closet.” Elsewhere, on a skit titled “The Kiss,” Eminem addresses a real-life run-in with the law after a kiss with Kim turned into a fracas in a club, while the following tracks “Soldier” and “Say Goodbye Hollywood” detail the fallout of the incident and the pair’s subsequent divorce.

Mathers’ lighter side is revealed in “Hailie’s Song,” a heartfelt ode to his daughter, though Slim Shady reappears on “Superman,” which sees Eminem enjoying the single life, and hit single “Without Me,” which reverts to the rebellious comedy of previous albums.

Dealing with the continued fallout of his fame, 2004’s Encore was a thematic companion piece to The Eminem Show. This time, fictional and pointedly controversial lyrics were kept to a minimum, as Eminem answered public criticisms leveled at him. On “Yellow Brick Road,” he apologizes for using the N-word on a beat tape-recorded when he was 16, while on “Mockingbird,” which Eminem described as the most emotional song he’d ever written, he apologizes to daughter Hailie and adopted daughter Alaina for their chaotic upbringing.

Elder statesman

A four-year silence followed, during which Eminem dealt with the breakdown of his marriage and the death of his best friend, Detroit rapper Proof. When he returned in 2009, it was with the refreshingly honest Relapse, which saw him detail his private battles on the likes of “Déjà Vu.” Elsewhere, on “My Mom” he lays the blame for his problems at his mother’s door, while also acknowledging the similarities between them. Slim Shady wasn’t far behind, either, being let off the chain to bait fellow celebrities and prod at taboo subjects.

The album fared well with critics, though Eminem himself dismissed it on his 2010 follow-up Recovery, which found him attempting to contextualize himself within a shifting hip-hop landscape. For all the self-doubt, however, there were still plenty of examples of lyrical prowess, while on “Going Through Changes” he’s at his most emotionally direct on grief at the loss of Proof and his ongoing love for Kim, despite their irreconcilable differences.

Eminem was back to his combative best on 2013’s The Marshall Mathers LP 2, an album which revisited his most celebrated work from a more mature standpoint: “Bad Guy” is a sequel to “Stan,” which finds the deceased fan’s little brother returning to kill Eminem, while “Rap God” unleashes Slim Shady once more on some of the most dexterous raps of his career.

Abandoning some of the self-examination that had been the focus of recent works, Mathers was in a more conciliatory mood when he issued an apology to his mother on “Headlights,” while the album also saw him train his sights on preconceived notions of morality, delivering some stark and deeply personal confessionals. Harnessing the strengths that have made Eminem one of the most compelling lyricists in hip-hop history, The Marshall Mathers LP 2 also left fans eagerly awaiting the next installment.

By the time that came, in the shape of 2017’s Revival, Eminem was arguably at his most personal yet. At the heart of the album laid his need to vent political frustrations and lay his soul bare, with the likes of “Walk On Water” seeing Mathers at his most vulnerable, “Bad Husband” finding him apologizing to Kim, and “Castle” penning a heartfelt ode to his daughter. While his invectives against the Trump administration (“Untouchable,” “Like Home”) were thrilling, and Slim Shady mischief never too far away (“Remind Me,” “Framed”), Revival showed that, as the former enfant terrible of rap transitioned into one of hip-hop’s elder statesmen, he was also more likely to speak from the heart than hide behind his alter ego.

Listen to the best of Eminem on Apple Music and Spotify.