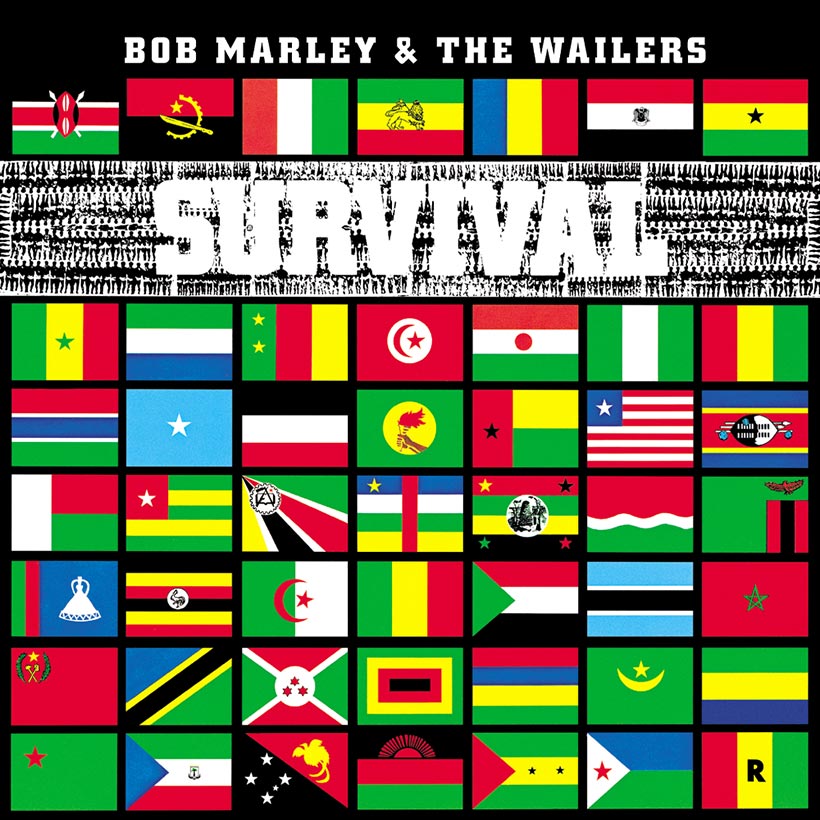

Powerful, pointed, and political, Survival was as close as Bob Marley came to producing a concept album. Released on October 2, 1979 in a sleeve bedecked with the flags of every country on the African continent, it was recorded at Basing Street Studios, London, and in Marley’s own Tuff Gong studio in Kingston. For the first and only time, Chris Blackwell was not involved in the production duties, which were shared between Marley and Alex Sadkin, a Blackwell protégé who had worked as an engineer on Rastaman Vibration.

The social and economic situation in Jamaica by this time was dire. The governing People’s National Party, led by Michael Manley, had generously expanded public spending on health and education, but without giving much thought as to how this would be funded. Price controls and consumer subsidies, although well-intentioned, further aggravated a balance of payments deficit. With exports in steep decline and an acute shortage of investment, the Jamaican economy went into freefall. Empty supermarket shelves, frequent power cuts, and an unemployment rate estimated at 30-40% brought a mood of anger and despair that sparked three days of rioting on the streets of Kingston in January 1979.

In the midst of such hardships, Marley maintained his local hero status. He played a starring role in the second Reggae Sunsplash festival in Montego Bay on 7 July, although heavy rains made it more of a reggae mudsplash as the Wailers treated the 15,000-strong crowd to previews of songs from Survival along with many old favorites. And the band showcased more new songs, ahead of the album’s release, at a children’s benefit show in Kingston’s National Arena on 24 September.

But in truth, Marley had become disillusioned with the political process in Jamaica. “Only one government me love, the government of Rastafari,” he said. While he remained very much a champion of the underclass and a committed agent of political change, his attention was now more urgently focussed on Africa instead. Significant in this regard was the Wailers’ headlining appearance at the Amandla Festival of Unity at Harvard Stadium in Boston, Massachusetts on 21 July 1979 where, in front of a gathering of 25,000 fans and international activists, Marley made a string of passionate speeches between numbers calling for African unity and freedom from colonial rule.

During his first visit to Africa, the year before, Marley had stayed in Shashamani, a Rastafarian settlement in Ethiopia where he wrote several of the numbers that set the tone and direction of Survival. Most notable of these was “Zimbabwe,” a song of remarkable prescience, given that the country it referred to had yet to achieve independence and was still known by its colonial name of Rhodesia. Yet Marley’s music had long resonated with its people: guerrilla soldiers who fought for independence in the Patriotic Front would play his music for inspiration; when Zimbabwe staged its celebrations at Rufaro Stadium in Salisbury (later renamed Harare), on April 18, 1980, Marley was the only outsider invited to perform.

A two-man delegation was flown out to personally invite Marley to the event. Marley (who would later claim that the invite was the greatest honor of his life) paid his own – and his band’s way – over to Zimbabwe from Jamaica, while also footing the bill not only for their instruments but a full PA system to be transported to Zimbabwe from London. The show, which began with the lowering of the British flag and the raising of the Zimbabwe one, was a highly charged event attended by both HRH Prince Charles and President Mugabe, and a flood of people eager to see their icon perform in person. With Marley whipping his fans into a frenzy, the police fired a round of tear gas into the crowd, forcing the band temporarily to abandon the show until order was restored. In an attempt to quell the storm, Marley would end up performing a second concert for free, the day after independence day.

While Marley’s music had become a soundtrack to the story of liberation in Africa, his status in America was less clearly defined. Although a favorite among the alternative/college rock fraternity, Marley and the Wailers had made surprisingly little impact on the traditional black music audience. In an effort to reposition themselves, the band began the Survival tour, on 25 October 1979, with seven sold-out shows (over four nights) at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, New York. They were the first reggae act to play this venue made famous in the 1950s and 1960s by James Brown and many other R&B legends. Performing against a series of heavily symbolic backdrops including the Ethiopian flag, a portrait of Haile Selassie, and a collage of Marcus Garvey and other American black power activists, the Wailers signaled a new sense of gravity in a show which the NME described as “full of thought and purpose.” Not unlike Survival itself.

An album that produced no hit singles, Survival was a deep and powerful meditation on the historical struggles of the black peoples in general, and a plea for the liberation and unification of Africa in particular. Here was the brooding essence of Marley as a rebel with a whole world of cause. “We’ve been trodding on ya winepress much too long,” he sang in “Babylon System,” a call for an ending of oppression – period. “Babylon is everywhere,” Marley said when called upon to explain the precise workings of a Babylon System. “You have wrong and you have right. Wrong is what we call Babylon.”

The theme of survival in the face of often murderous injustice ran through several songs, including the title track and the autobiographical “Ambush In The Night,” about the attempt on Marley’s life in 1976: “All guns aiming at me…We keep on surviving.” But while Marley made some heavy political points in songs such as “Africa Unite,” “Top Rankin’,” and “So Much Trouble In The World,” he remained, as his biographer Timothy White put it, “always more of a mystic than a Marxist.”

Adopting a more optimistic tone for the sunny groove of “One Drop,” he once again praised Jah (God), whose spirit apparently resided in the drumbeat of Carlton Barrett. And on “Ride Natty Ride” the singer portrayed himself as a man on a mission that would not be denied: “No matter what they do/Natty keep on coming through.”

Without any hit singles, Survival enjoyed only moderate chart success, peaking at No.20 in the UK and at No.70 in the US. But the album stands as a towering monument to the depth of Marley’s convictions and the increasing scope of his ambitions musically, politically, and culturally. The album signed off with “Wake Up And Live” a sensational funk/reggae groove freighted with a message that was both inspirational and grimly prophetic: “Live big today/Tomorrow you buried in a casket.”

Survival can be bought here.