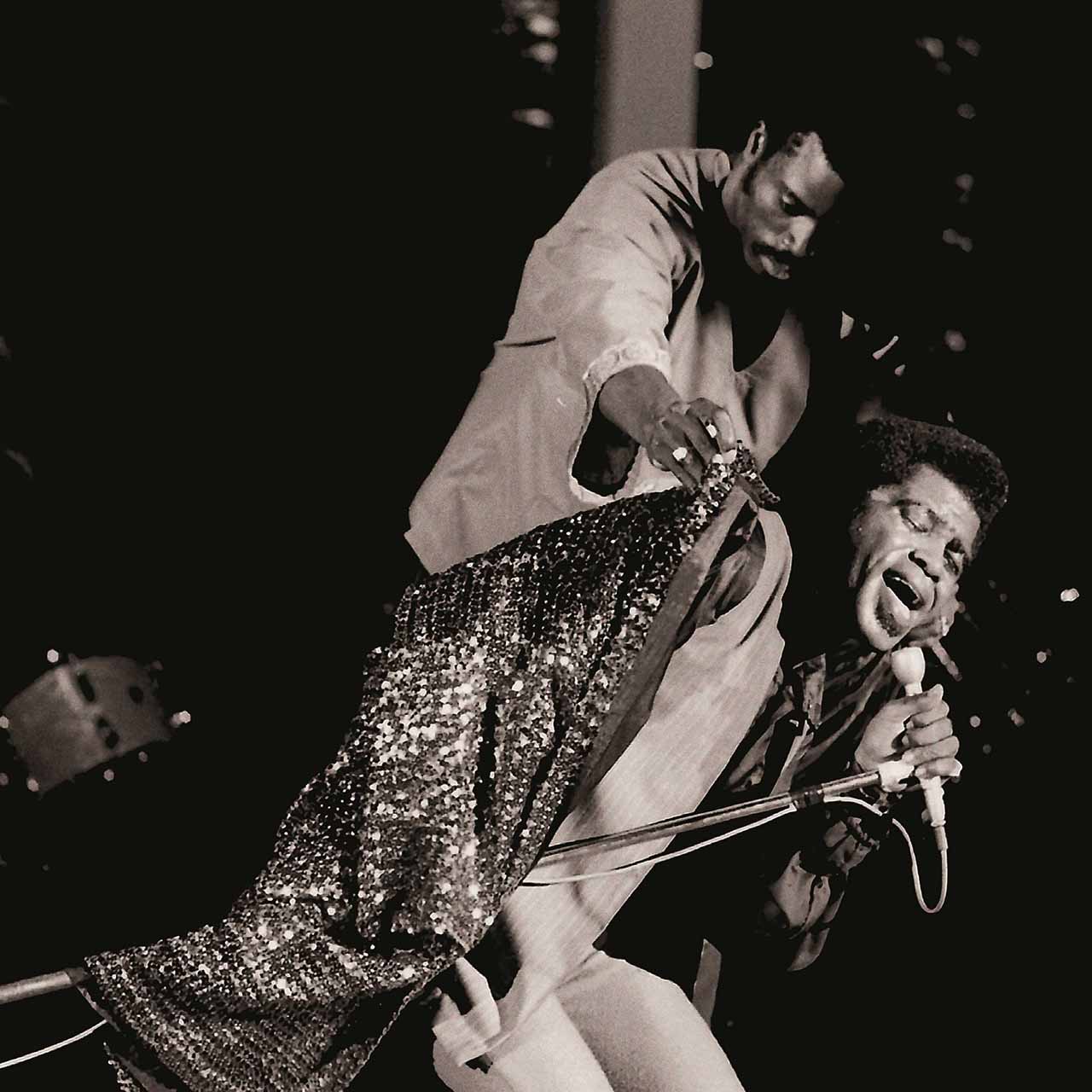

James Brown invented funk, the foundation stone for hip-hop, a lot of pop and disco music, and the groove he introduced also kept a lot of jazz musicians afloat. He was the No. 1 artist for an African-American audience in the 60s and early 70s, and a wider audience came to his work without the singer specifically tailoring it for them. Musicians with reputations for high art, such as Miles Davis, admired this supposed purveyor of raw grit. It was like James Brown had the soul, the feet, the heart, and the hips on speed dial. He was a funk machine as well as a sex machine, black and proud to the bone. He was his Bad Self, and he never forgot where he came from – and when at home with his bad self, as captured on a recently unearthed 1969 live recording, he was incendiary.

Listen to Live At Home With His Bad Self on Apple Music and Spotify.

Connected to the South

James Brown grew up in Georgia, poor like dirt. His autobiography remembers him playing with bugs underneath the timber shambles he called home. He had to shine shoes and dance for pennies to earn pocket money, and perhaps inevitably, as a teenager, he was arrested on Broad Street, Augusta, and jailed for robbery.

It was a predictable path for a poor African-American kid in a society that saw kids like him as a problem – if they thought about them at all. But Brown got out of prison thanks to his musical talent and the sponsorship of the Byrd family – and when he joined Bobby Byrd’s group, The Flames, Brown’s breathtaking ability meant he had to be out front.

In the early 60s, Brown stopped being a small-town Southerner and became a city slicker, delivering soul and practically founding funk as we know it. During that decade, New York became his stronghold, as two smash hits Live At The Apollo albums testified, and he bought a house in Queens. But in his heart, Brown was still connected to the South. Didn’t he deliver “Georgia On My Mind” so passionately? Didn’t he still sing the blues on occasion, though he claimed he didn’t enjoy this musical style?

James Brown had unfinished business in Augusta. It had created him, incarcerated him, and refused to have him back when he came out of prison. But he reached the top all the same – like nobody else of his ethnicity, and by catering largely for his brothers and sisters. Mr. Brown wanted to show Augusta how far he’d come – and that he hadn’t forgotten his origins, because he would not only celebrate his success in Augusta, he’d also generously help kids who suffered like he had: the poor, the uneducated, the hungry. He was an example and an exemplar: this is what you could be, with hard work and the right breaks. And if you couldn’t be James Brown, then James Brown could at least ease your burden a little bit.

A homecoming

Brown went back to his roots before it was fashionable. He bought an apartment in Augusta, followed by a house in a part of town where African-Americans were more usually the hired help. Brown decided to record a live album at the Bell Auditorium, Augusta, marking what he saw as his homecoming. It would be called Live At Home With His Bad Self – and his fans took note of his live albums like those of no other artist, ever since 1962’s electrifying Live At the Apollo had shipped records like they were singles. Live At Home With His Bad Self was bound to be big.

Mr. Brown played the Bell Auditorium on October 1, 1969, and this killer combination – a singer at his absolute peak with a band that had been with him through the invention of funk – delivered two sets, both recorded. After the audience went home, he called his exhausted band back for a private set, also committed to tape. Once it was in the can, engineers worked on the tracks, getting a balance and dubbing cheering to some of the late-night empty hall material. Soon Brown had everything he needed for Live At Home With His Bad Self. But the record never came out.

Brown calling the band back to work that night was not a one-off. This mighty but overworked group was at the end of its tether, and there was talk of a revolt. Within months, things came to a head, and, faced with demands for a better deal, the Godfather Of Soul took a hard line, sacking his entire orchestra, except for one of his three drummers, John “Jabo” Starks.

The band went off to record as Maceo & All The King’s Men, named after sax supremo Maceo Parker, and Brown replaced them with The Pacemakers, a Cincinnati group built around brothers William “Bootsy” Collins (bass) and Phelps “Catfish” Collins (guitar), though the prodigiously talented Bootsy was just a teenager. They knew Brown’s set – many young black musicians did – and started gigging with Brown immediately as The JB’s. Their brilliance was confirmed when they cut the single “Get Up (I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine,” a new, stripped-down sound, making 1970 one of Brown’s high points. They breathed new life into Brown’s funk, and he launched their stellar careers. But now he had a new sound, Live At Home With His Bad Self seemed anachronistic.

Bad – in a good way

Brown ditched the album and cut a fresh one, Sex Machine, his new band playing a live set in the studio. Because his last live album, Live At The Apollo, Volume II, was a double, Brown edited the Live At Home… tapes heavily, slowing some tracks down, and selected some to fill out Sex Machine, but half a dozen vital performances failed to make the cut. While the result was musically agreeable, it seemed a bit strange: two bands, precious music messed with, history rewritten. But in 1970, Brown was thinking about the moment, not his legacy. Much of his formerly all-important Augusta homecoming album was canned.

Brown’s new band was too young and wild to stick around; Bootsy only worked with the Godfather for 11 months. Brown’s old crew returned, cutting some of the most vital music of the early 70s. The Augusta tapes were left undisturbed for decades. Now, at last, thanks to diligent research and restoration, 50 years after its recording, we can hear the Live At Home With His Bad Self as it really was, and it is Bad – in a good way.

Cooking, pure, and totally live

The funk is here. The album kicks off totally energized, thanks to a five-minute-plus “Say It Loud – I’m Black And I’m Proud,” Brown delivering its message with joy and militancy, and following it with a short speech that’s powerful and touching. We get a groovin’ cut of “Lowdown Popcorn,” featuring his bad self on organ. There’s “I Don’t Want Nobody To Give Me Nothing,” with a ballsy solo from Maceo Parker; “I Got The Feelin’’ is more frantic and flows into a driven “Lickin’ Stick-Lickin’ Stick.” “There Was A Time,” Brown’s extended vamp built to let him bust some moves, follows. Since the second verse concerns the city he was playing in, and he introduces local people, it’s a sizzling seven minutes.

There’s a terrific cut of “Give It Up Or Turn It A Loose” with “Sweet” Charles Sherrell proving that Bootsy didn’t have the original bragging rights on basslines so funky they are almost abstract. A stinging and terse “I Can’t Stand Myself,” and an extended, furiously funky “Mother Popcorn,” closes the affair, in a superior mix to a previously available version – if it doesn’t hit you, you must have unnatural funky immunity.

There are ballads, too, such as “Try Me,” accompanied by the occasional scream; and an OTT “It’s A Man’s Man’s Man’s World” that becomes emotional during the breakdown, with Jimmy Nolen’s guitar licks dripping with feeling. Even the stage musical ballad “If I Ruled The World” is loaded with meaning when the future “Funky President” sings it. A version of his then-current hit, “World,” finds him performing to a taped backing, an anomaly he explains to the crowd. It’s great, by the way, though entirely a product of its time. The rest of the album is cooking, pure, and totally live. This is the way it was for James Brown in 1969.

Brown’s homecoming continued. He made Augusta his HQ and bought a mansion just across the Savannah River from the city. He held annual events to help impoverished local citizens and became Augusta’s No.1 son, which named a street after him. The Bell Auditorium is now part of an entertainment complex that includes the much larger James Brown arena.

For a time, James Brown, the man who created funk, the most important black musician of the 60s, was known as ‟The Man Who Never Left.” When it came to Augusta, in his soul that was true. Live At Home With His Bad Self, revealed in its full glory at last, shows just how much the city meant to him.