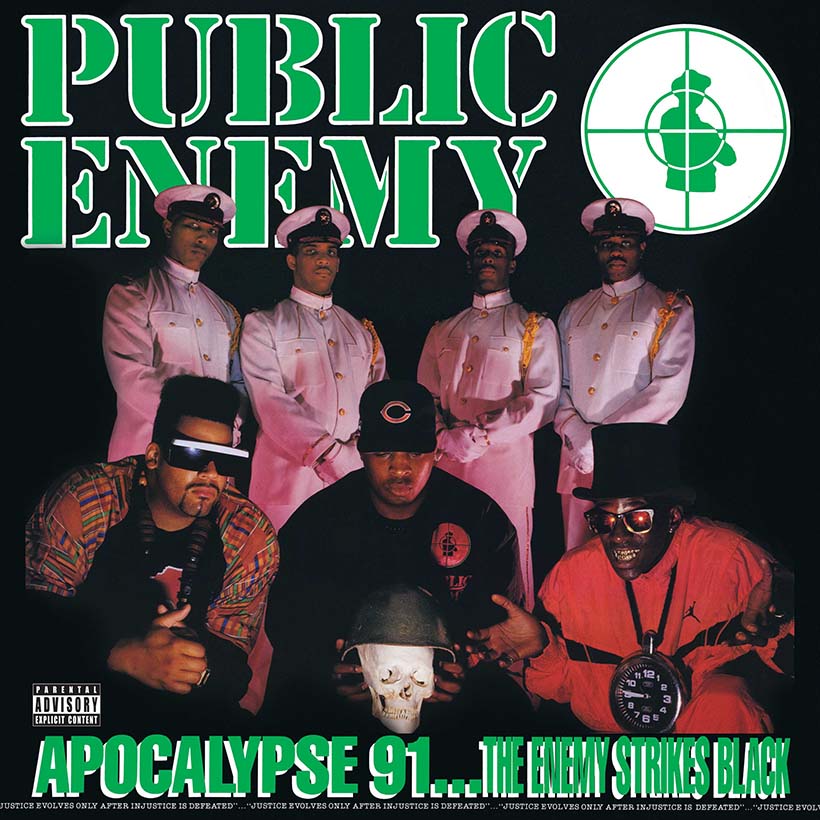

The making of Public Enemy’s fourth album, Apocalypse 91: The Enemy Strikes Black, had hit its stride. Recorded primarily at The Music Palace studios in Long Island, the album found Chuck D, Flavor Flav, Terminator X, the S1Ws, Gary “G-Wiz” Rinaldo, and the Imperial Grand Ministers of Funk lighting the studio on fire with blazing socio-political commentary and heart-thumping production.

Then disaster struck.

Parked outside of a Soho studio, longtime Public Enemy producer Hank Shocklee was the victim of a robbery. The thieves made off with the bones of every track they’d been working on, bringing an abrupt halt to any progress they’d made.

“We never really recovered after that,” Hank Shocklee once said. “We was on a roll – I was on a roll. To lose that material set me back so hard.”

Public Enemy was in the midst of a legendary run: Yo! Bum Rush The Show in 1987, It Takes A Nation of Millions… To Hold Us Back in 1988, and Fear of A Black Planet in 1990. The group was a revolutionary force unafraid to bring injustice to light in the brashest ways possible.

Apocalypse 91 was different. Initially intended to be an EP, Apocalypse 91 morphed into a fully fleshed-out album by the summer of 1991. Anchored by the unexpected hybrid of Anthrax and Public Enemy’s “Bring The Noise” collaboration, the 16-track project marked a change in direction for the group. Following the robbery, what they emerged with was a more minimal album, production-wise, than previous efforts. The Bomb Squad had been relegated to the role of executive producers rather than its principal architects, while G-Wiz – who was just finding his footing as a producer at the time – Stuart Robertz and Cerwin “C-Dawg” Deppe took the helm.

Listen to Public Enemy’s Apocalypse 91… The Enemy Strikes Black.

Yet some of Public Enemy’s most engaging and commercially successful material emerged from Apocalypse 91, including “Can’t Truss It,” which peaked at No. 9 on the Hot Soul Singles chart and No. 50 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Coupled with its polarizing and shocking video, the song painted a graphic depiction of slavery and the ongoing plight of Black people.

“By The Time I Get To Arizona” further ruffled feathers, with its condemnation of former Arizona governor Evan Mecham, who refused to recognize Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday. The video for “By The Time I Get To Arizona” aired only once on MTV upon its release before it was banned for its controversial themes that included Mecham’s fictional assassination.

Once was enough for Chuck. “We knew it was probably going to be banned and it was,” he says. “All it had to do is be shown once. We said, ‘You know what? If this video just gets seen one time, that’s all it needs.’ And I was on tour at that time, so when I did interviews, we were making a statement that we thought the United States was being derogatory by not acknowledging the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, so we decided to get cinematic.”

What many don’t know is “Arizona” was initially meant to go over the “Shut Em Down” beat. “When we found something that was more apropos for ‘Arizona,’ [then] the ‘Shut ‘Em Down’ beat was wide open for me to write the song. I think I was doing the ‘Nightrain’ video, and I kept hearing this guy talking about how [Kool DJ] Red Alert was killing it on the radio, and I was like, ‘Yo, Red Alert is shutting them down, man.’

“So what I happened to write on, we called it the bald beat or the bald experience ‘cause it was just nothing but a stripped down beat, which was a total flip to what we had known. The whole thing about Public Enemy is we wanted to make every album different from another, so you couldn’t tell what the next album would be, because we would totally flip the script.”

Public Enemy fans will never know what Apocalypse 91: The Enemy Strikes Black would’ve sounded like had Shocklee not been robbed. Chuck says there’s still a debate whether the car was left open or broken into that day on Green Street. But like Chuck says, “If you fall on your face, you gotta get up off that fucking ground and keep moving.”

Despite Shocklee’s misgivings about the album, it was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in November 1991. Its 52-minutes of innovative production and potent commentary on the socio-political climate, systemic racism, and American media are topics that are, unfortunately, still relevant today.

Listen to Public Enemy’s Apocalypse 91… The Enemy Strikes Black.