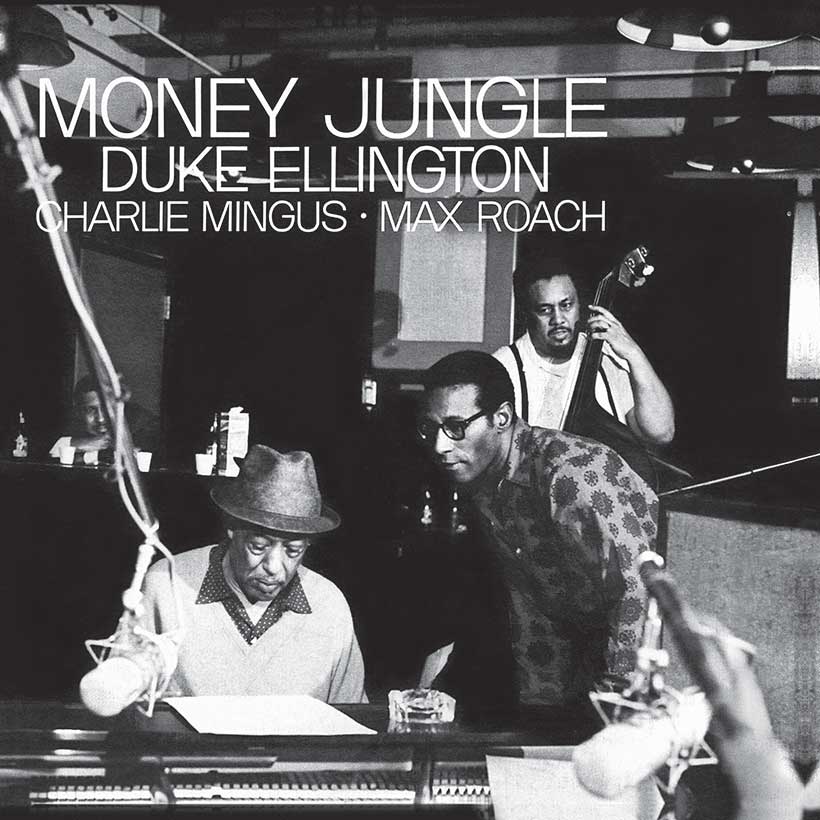

First released in 1962 via the United Artists label, Duke Ellington’s collaboration with bassist Charles Mingus and drummer Max Roach, Money Jungle, was a momentous jazz summit. Though often seen as the moment where the old guard (Ellington) squared up to jazz music’s young lions (Mingus and Roach), the generational differences between its three participants are often exaggerated. Certainly, Ellington was entering his twilight years – he had just turned 63 – but Mingus, then aged 40, and the 38-year-old Roach were hardly wet behind the ears when the album was recorded.

Perhaps a more accurate way of looking at the trio’s musical marriage is to see Ellington as a revered establishment figure pitted against modernist revolutionaries. Ultimately, though, the result of their collaboration wasn’t a confrontational face-off but a joyous celebration of jazz created by three unlikely kindred spirits.

Listen to Money Jungle on Apple Music and Spotify.

As far apart as the North and South Poles

On paper, the pairing of the urbane Ellington with Mingus, a roughneck firebrand renowned for his volcanic temper, seems potentially explosive. But the bass player was a great admirer of the older musician, citing the jazz aristocrat as a critical influence in his approach to composition. They were not strangers, either, as Mingus had briefly been in Ellington’s band in 1953, though he suffered an ignominious exit: fired after four days for attacking another band member.

Max Roach, too, had enjoyed a short stint with Ellington, in 1950; a decade later, he played on the pianist/composer’s Paris Blues soundtrack. Ellington, then, was familiar with both men and had been an avid follower of their musical exploits. Recalling the Money Jungle session in his autobiography, Music Is My Mistress, Ellington described his younger collaborators as “two fine musicians,” though he also remarked that their personalities were “as far apart as the North and South Poles.”

Nothing should be overdone, nothing underdone

According to Ellington, record producer Alan Douglas instigated the idea of Money Jungle. Douglas had worked with Ellington in Paris, in 1960, and on returning to the US he got hired by United Artists. Immediately calling the pianist, Ellington suggested that he work with Mingus and Roach in the studio. Ellington agreed, later recalling, “Charles Mingus and Max Roach were both leaders of their own groups, but what was wanted now was the kind of performance that results when all the minds are intent on and concerned with togetherness. Nothing should be overdone, nothing underdone, regardless of which musician was in the prime spot as a soloist.”

The three musicians certainly achieved that goal: such was their chemistry as a unit, they sounded as if they had been playing together for years. Despite Ellington’s seniority, in terms of age and accomplishments, the three men went into New York’s Sound Makers Studios on Monday, September 17, 1962, as equals. The session wasn’t entirely stress-free, though. Rumors persisted that Mingus – apparently unhappy that all the music was Ellington’s – stormed off midway, only to be coaxed back by the pianist.

An instinctive sense of swing

Seven Ellington tunes appeared on the original vinyl release of Money Jungle. Three of them, the dreamy “Warm Valley,” the eastern-flavored “Caravan,” and the wistful ballad “Solitude,” were fresh takes on well-known Ellington numbers. The remainder, however, were newly penned for the session.

Ellington hammers his piano as if possessed on the opening title song, an angular, almost avant-garde number whose dissonances share an affinity with Thelonious Monk’s music. Driven by Mingus’ sawing bass and Roach’s turbulent polyrhythms, the track crackles with fiery, kinetic synergy.

In sharp contrast, “Fleurette Africaine,” which became a regular fixture in Ellington’s concert repertoire after Money Jungle’s release, possesses a shimmering delicacy. Though Ellington displayed a lyrical side in his ballads, his uptempo material on Money Jungle – such as the propulsive “Caravan,” “Very Special,” and the jaunty “Wig Wise” – bore the imprint of a musician who instinctively knew how to swing.

Part of the same continuum

Playing alongside two younger musicians on Money Jungle appeared to invigorate Ellington, who attacked his piano with palpable vigor and a defiant sense of musical virility. His ultra-dynamic performance, along with the freshness of his newly-minted compositions, showed that he was still a relevant figure in jazz, four decades after he began making a name for himself. As someone who was never content to stand still musically, the pianist was, in fact, as much of a modernist as Mingus and Roach.

But though it revived his career (Ellington’s next album would be recorded with John Coltrane), Money Jungle wasn’t just about the legendary bandleader. It was about three musicians’ mutual respect and admiration, stemming from the joy of their collaboration. The record revealed that, though jazz had its factions and different styles, musicians could find common ground in the simple purity of their love for playing music together. Early on in their careers, Mingus and Roach seemed to be young upstarts challenging the status quo represented by figures like Ellington. The revelatory Money Jungle showed that they were all part of the same continuum.

Listen to Money Jungle on Apple Music and Spotify.