Guided by their single-minded frontman, Mark Hollis, Talk Talk recorded a trio of career-defining albums during the late 80s and early 90s. The band hit on a winning formula in 1986 with the sublime The Colour Of Spring, but they took a radical turn into leftfield with 1988’s Spirit Of Eden and traveled even further out on 1991’s otherworldly Laughing Stock.

Widely regarded as Talk Talk’s holy trinity, these singular, pigeonhole-defying albums are thrown into even sharper relief when you consider that EMI initially marketed Hollis’ team as a glossy, synth-pop act akin to labelmates Duran Duran. However, after the Top 40 success of 1982’s The Party’s Over and 1984’s It’s My Life, Hollis asserted creative control for The Colour Of Spring: a gloriously-realized widescreen pop record which spawned the band’s two signature hits, “Life’s What You Make It” and “Living In Another World.”

A groundbreaking album

Talk Talk’s commercial peak, The Colour Of Spring yielded worldwide chart success and sales of over two million. However, the band shunned such materialistic concerns for 1988’s Spirit Of Eden, which was edited down to six tracks from hours of studio improvisation by Hollis and producer/musical foil, Tim Friese-Greene.

A truly groundbreaking album flecked with rock, jazz, classical and ambient music, Spirit Of Eden attracted critical acclaim and cracked the UK Top 20, but Mark Hollis remained adamant that Talk Talk wouldn’t be touring the record. After dealing with time-consuming business-related issues, the band then left EMI and recorded their final album, Laughing Stock, for legendary jazz imprint Verve Records.

As manager Keith Aspden told The Quietus in 2013, Verve offered Hollis and co the opportunity to further embrace the experimental approach they’d adopted while piecing Spirit Of Eden together. “Verve guaranteed full funding for Laughing Stock, without interference,” he said. “[The band] took full advantage of that situation and locked themselves away for the duration of the recording.”

Extreme methodology

By this stage, Talk Talk was ostensibly a studio-based project centered upon Hollis and Friese-Greene, but augmented by session musicians including longterm drummer Lee Harris. As Aspden suggests, they holed up in north London’s Wessex Studios (previously the birthplace of The Clash’s London Calling) with one-time David Bowie/Bob Marley engineer Phill Brown, where they stayed for almost a year honing the six tracks that make up Laughing Stock. The methodology involved was truly arcane, with windows being blacked out, clocks removed and light sources limited to oil projectors and strobe lights in an attempt to capture the correct vibe.

“It took seven months in the studio, though we took a three-month break in the middle,” Brown recalled in 2013. “I guess from getting involved to studio recording, mixing and mastering took up a year of my time. It was a unique way to work. It took its toll on people, but gave great results.”

A quest for perfection

Brown wasn’t joking: Laughing Stock was painstakingly edited down to its 43-minute running time from a series of lengthy improvisational sessions. Hollis cited other genre-defying masterpieces such as Can’s Tago Mago, and Elvin Jones’ drumming on Duke Ellington and John Coltrane’s 1962 recording of “In A Sentimental Mood” as influences upon the album, and his quest for perfection was further fueled by his desire to capture the magic of spontaneity in the recordings.

“The silence is above everything,” he told journalist John Pidgeon at the time of the record’s release. “I would rather hear one note than I would two, and I would rather hear silence than I would one note.”

Less is certainly more where Laughing Stock is concerned. Opening track “Myrrhman” commences with 15 seconds of amplifier hiss; the enigmatic closing number, “Runeii,” features swathes of ambient space; and the fascinating nine-minute centerpiece, ‘After The Flood’, is underpinned by droning, ethereal strings which only gradually drift into focus.

However, while these tracks are arguably even more minimal in design than Spirit Of Eden, they’re offset by more quixotic songs such as “Ascension Day” and “Taphead,” which make sudden, jarring leaps from gentle, quasi-ambience to rushes of coruscating noise. Taken as a whole, Laughing Stock can initially be a disorienting listen, but with repeated plays its bewitching beauty steadily seeps out, perhaps nowhere more so than on “New Grass,” the record’s most bucolic and linear-sounding track, which alone is worth anyone’s price of admission.

A poignant swansong

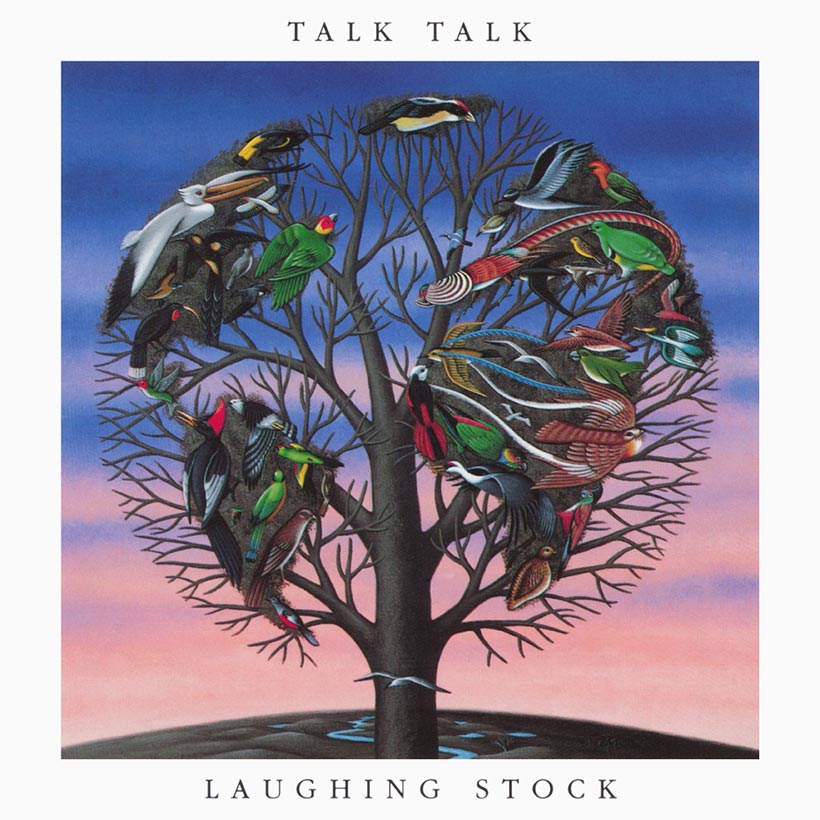

Housed in a memorable sleeve designed by long-term collaborator James Marsh, Laughing Stock was first released by Verve on September 16, 1991. Even though it didn’t contain a radio-friendly single or support from live shows, the album still briefly sneaked into the UK Top 30. With little fuss, Talk Talk disbanded shortly after, with Mark Hollis later releasing one final understated masterpiece, his self-titled 1998 solo album. Sadly, it proved to be the last album bearing his stamp before his untimely death, aged 64, on 25 February 2019.

As is often the case with forward-looking artistic statements, Laughing Stock polarized critical opinion on release. However, a few of the more perceptive reviews, such as Q’s (“It might put Talk Talk heavily at odds with the commercial charts… but it will be valued long after such superficial quick thrills are forgotten”) proved prescient, as the album’s reputation has grown steadily with the passing of time. In recent years, artists as disparate as UNKLE, Elbow, and Bon Iver have sung Laughing Stock’s praises, and it’s not hard to hear why. This bold, indefinable record is both a poignant swansong and very possibly Talk Talk’s crowning glory.