Fate, timing, destiny, serendipity: There are many words to describe uncanny sequences of events that transform artists into icons, creators whose legacies stand the test of time. Jazz musicians like Miles Davis and John Coltrane embarked on musical journeys that led them to become deity-like archetypes of their era. Nonetheless, there is a lesser known musician who sits nestled in the crevice of jazz history that played an integral part in Davis and Coltrane’s artistic lives. His name is Julian “Cannonball” Adderley.

Jazz musicians and fans may know him very well. The same goes for those born before the 1960s. But Adderley’s name, for reasons that may simply have to do with timing and circumstances, does not live on the tongues of the mainstream popula, even though his contributions to jazz were essential to the genre’s evolution.

Listen to the best of Cannonball Adderley here.

Born into a family of Florida educators, his musical training afforded him the ability and poise to play in any environment without effort or trepidation, and Adderley proved this shortly after his arrival in New York City in 1955 after establishing himself as a well-known teacher and musician in and around Fort Lauderdale. He was initially in town with plans to search for a graduate school to attend, but fate had other plans for him on the night he casually walked into Café Bohemia in Greenwich Village with his saxophone in hand.

Adderley’s arrival in the New York jazz scene feels a bit like a fairy tale: A young saxophonist from a faraway land (the South) arrives just three months after Charlie “Bird” Parker has passed away in 1955, and is asked to step in for Oscar Pettiford’s saxophonist at a small club in Greenwich Village called Café Bohemia. No one has heard of him before, but his playing that night makes him a literal overnight sensation. Many saw Adderley as the successor to the throne of Charlie Parker, and labels were eager to sign him.

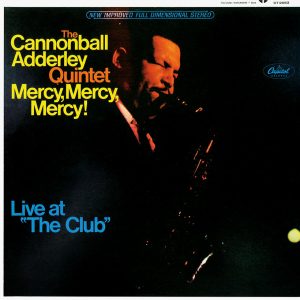

Over the next decade, Adderley would release over 30 albums which included collaborations with Nancy Wilson, Milt Jackson, Wes Montgomery, Kenny Dorham, and others. These collaborations and his large output of work offered him legitimate notoriety in the jazz world. He went on to record a hit song entitled “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” that established his name in the world outside of jazz, climbing to No.11 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1967. White artists like Dave Brubeck and Herb Alpert had garnered success by offering consumable versions of jazz to white artists, but due to segregation – which had just been illegalized, Black American jazz musicians had few voices in mainstream music until “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” emerged and appealed to wider audiences.

But before that moment of mainstream recognition, Adderley’s sensual fusion of soul and gospel music made him one of the innovators of hard bop, a genre that derived directly from his rhythm and blues sensibilities. His fusion style made him an influence and sought after collaborator, particularly with Miles Davis. Indeed, in 1955, when Davis was looking to put together his first national tour, the trumpeter wanted Adderley as his alto saxophonist. Unfortunately, Adderley was unable to commit to the gig due to a teaching contract in Florida.

Is it possible that if Adderley joined the tour instead of a young John Coltrane, he would have gone down in history as the yin to Davis’ yang? Fate played a hand that favored Coltrane as Davis’ musical counterpart, but Adderley was destined to work with Davis as a frontman, just as much as he was to play as a member of Davis’ band. A few years later, Cannonball recruited Davis to play as a sideman on Somethin’ Else, with Davis subsequently tapping Cannonball to play sax on the larger-than-life jazz opus Kind of Blue.

With this type of pedigree, one has to ask, how can Adderley possibly be overlooked today? He was the answer to the future of jazz in New York City in the 1950s. In the following decades, he’d not only infuse soul and gospel into his playing, but also rock and funk, widening the scope of the genre considerably.

Indeed, his catalog in the 60s and 70s is incredibly diverse: He recorded an album with the jazz singer Nancy Wilson in 1961; he worked with an orchestra on 1961’s African Waltz; he created an electronic rock and jazz fusion album entitled The Black Messiah in 1971; and explored his ancestry and mysticism, respectively, with 1968’s Accent on Africa and 1974’s Love, Sex and the Zodiac.

Without acknowledging Adderley in the conversation of jazz greats alongside Coltrane and Davis, we do a disservice to history. Cannonball was not only playing with them, he was an equal and – at times – the leader. He should not be seen as a demigod in the history of jazz, but an indispensable partner in pioneering and innovating.

This article was originally published in 2020. We are re-publishing it today in celebration of Cannonball’s birthday. Black Music Reframed is an ongoing editorial series on uDiscover Music that seeks to encourage a different lens, a wider lens, a new lens, when considering Black music; one not defined by genre parameters or labels, but by the creators. Sales and charts and firsts and rarities are important. But artists, music, and moments that shape culture aren’t always best-sellers, chart-toppers, or immediate successes. This series, which centers Black writers writing about Black music, takes a new look at music and moments that have previously either been overlooked or not had their stories told with the proper context.