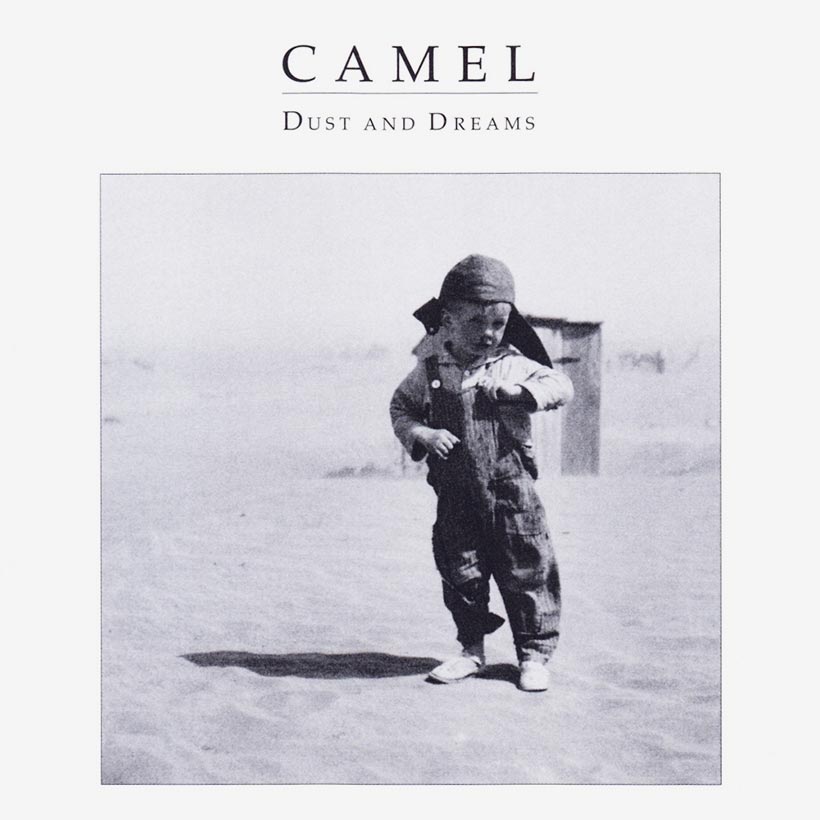

The first release on frontman Andy Latimer’s own Camel Productions imprint, Camel’s 11th studio album, September 1991’s Dust And Dreams, wasn’t just a strong comeback album – its advent marked the beginning of a renaissance for the stalwart Surrey prog-rockers.

Camel’s previous studio outing, the Cold War-related Stationary Traveller, came out in 1984, but after its succeeding live album, Pressure Points – recorded that same year at London’s Hammersmith Odeon – the band drifted off the radar. Indeed, during the late 80s, fans were understandably concerned by their lengthy radio silence.

Behind the scenes, however, business, rather than the pleasure of creating new music, occupied Andy Latimer’s thoughts. Several years elapsed while lingering legal and management-related issues were ironed out, and, after Pressure Points, Camel and Decca – their label of 10 years – amicably parted ways, leaving Latimer and co free to sign a new deal.

In the end, however, Latimer made a more radical move: selling his London home in 1988 and moving to California, where he built his own studio, wrote much of the material for Camel’s next album, and set up his own label to release it.

Perhaps influenced by his new surroundings, the song cycle Latimer conceived was for a concept album evoking the spirit and themes of John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer (and later Nobel) Prize-winning 1939 novel, The Grapes Of Wrath. Later adapted for the silver screen by director John Ford, this American classic concerned the plight of the Joad family: poor, US Great Depression-era Oklahoma folks who mistakenly believe California to be the promised land and thus relocate, only to suffer even greater hardship.

Inspired by these universal themes, Latimer penned Dust And Dreams: an introspective masterpiece, which – unlike the relatively concise, song-based Stationary Traveller – was based primarily upon evocative instrumental music. Released on 10 September 1991, the album consisted of 16 tracks, though a number of these were enticing, neo-ambient workouts, often relatively brief and primarily illustrated by keyboards.

Fans thirsting for Camel at their virtuosic best, however, were rewarded by the album’s four fully-fledged songs. The stirring “Go West” reflected the Joad family’s optimism as they arrived in California, but by the time Dust And Dreams hit the elegiac “Rose Of Sharon” (“What we gonna do when the baby comes?”), their hopes had fallen apart at the seams. Elsewhere, the seven-minute “End Of The Line” and the dramatic, shape-shifting “Hopeless Anger” contained flash and flair redolent of mid-70s Camel classics The Snow Goose and Moonmadness.

Though not a chart hit, Dust And Dreams was well received and sold solidly, the impetus leading to an emotional world tour wherein Latimer was joined onstage by a new keyboardist, Mickey Simmonds, and his trusty rhythm section, Colin Bass and Paul Burgess. The highlights of a Dutch show on this tour were later captured for another dynamic live album, Never Let Go, which reinforced the impression that Camel was most definitely back in business.