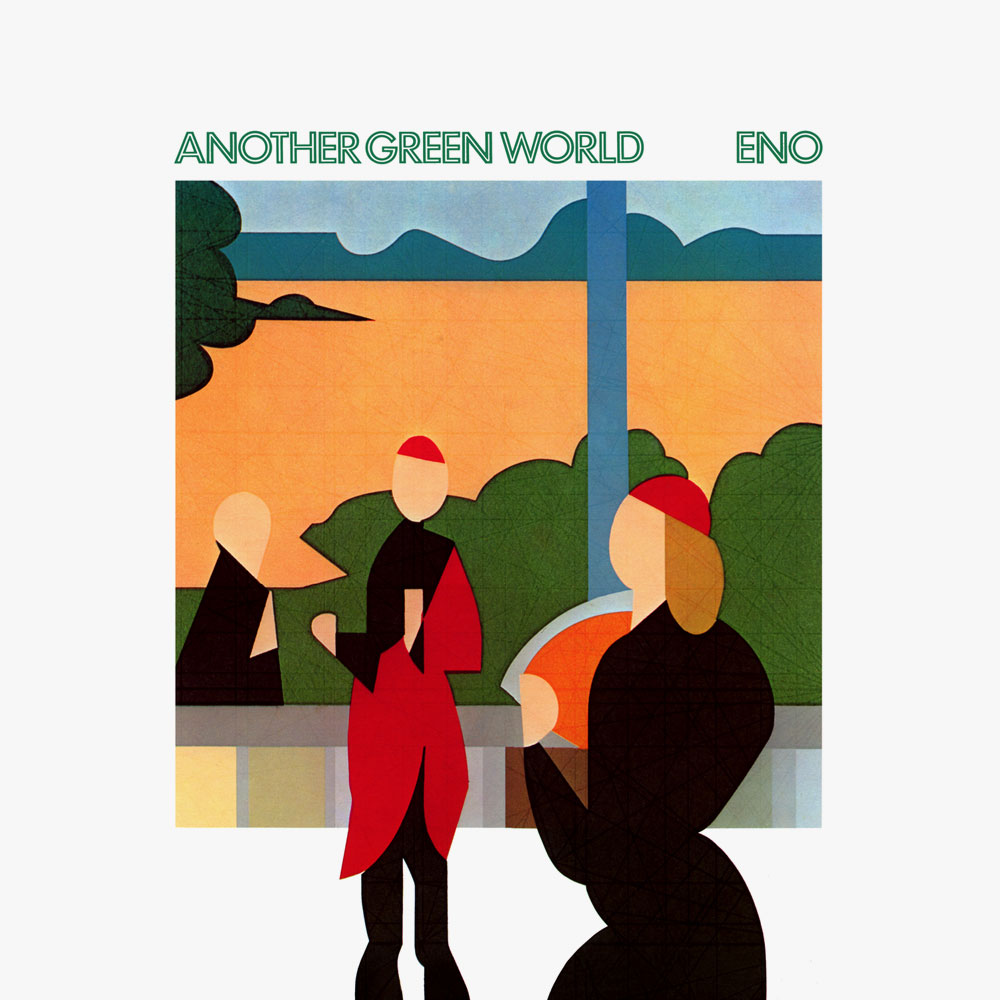

The much-loved title sequence of the BBC’s Arena arts documentaries brilliantly sets the tone for what is about to follow. You know you’re going to be treated to something alluring, out of the ordinary and mentally stimulating – thanks, in no small part, to the accompanying music: a simple, circular theme of disproportionate beauty and an indefinable longing. The theme in question is the title track of Brian Eno’s third solo album, Another Green World, originally issued on Island Records in September 1975, and since reissued in a 180g double-vinyl pressing, mastered at half speed. Hindsight affords us the luxury of noting that this was another transitory undertaking, with Eno edging towards the ambient soundscapes that would characterize his output from 1978’s Music For Films onwards.

Listen to Brian Eno’s Another Green World now.

However, while Another Green World splits its focus between winningly elliptical pop songs and minimalistic instrumental pieces, it still benefits from an inner logic. Of significance is the album’s overall musicality: while still reveling in unexpected textures, and deploying the routine-derailing Oblique Strategies cards first used during the recording of his second solo album, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), Eno nevertheless seemed to welcome aspects of melodic orthodoxy as long as they could be relocated to a different neighborhood. The immaculately jazzy fretless basslines contributed by Brand X mainstay Percy Jones on “Sky Saw” and “Over Fire Island,” for example, make for an incongruous bed behind the industrial sound of Eno’s “snake guitar” (on the former) and static-prickled electronic squalls (on the latter).

Furthermore, Jones’ then-bandmate, Genesis/Brand X drummer Phil Collins, keeps the guest list on the illustrious side – even if his role on the instrumental “Over Fire Island” is to lay down a largely unadorned metronomic pulse. Velvet Underground deity John Cale, meanwhile, appends uneasy viola scrapes to “Sky Saw” as the track begins its long fade.

“St Elmo’s Fire,” “I’ll Come Running,” and “Golden Hours” reunite Eno with King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, with whom he had been collaborating since 1973’s proto-ambient (No Pussyfooting). For the solo in “St Elmo’s Fire,” Fripp was instructed to play as though approximating an electrical charge arcing between the poles of a 19th-century Wimshurst electrostatic generator – and was duly credited with “Wimshurst guitar” on the sleeve. Contrastingly, Fripp’s playing is itemized as “restrained lead guitar” on the elegantly unhurried (and somewhat Roxy Music-esque) “I’ll Come Running,” with its sweetly enigmatic lyrics: “You’ll see, one day these dreams will pull you through my door/And I’ll come running to tie your shoe.”

Between them, Fripp, Eno, and John Cale nibble at the margins of “Golden Hours,” which in its blank stasis suggests a Syd Barrett-style rumination on entropy and aging: “Several times/I’ve seen the evening slide away/Watching the signs/Taking over from the fading day/Perhaps my brains are old and scrambled.”

While the input of his guest musicians bears fruit, it is Eno himself who impresses the most. Armed with synths, piano, and guitars, and tackling the majority of the album’s discreetly pictorial instrumentals on his own – “In Dark Trees,” “The Big Ship,” the title track, “Sombre Reptiles,” “Little Fishes,” “Becalmed,” and “Spirits Drifting” – he displays a remarkable ability to make a limited technique convey a wealth of emotions and deeper meaning. These stately fragments, simultaneously sad, proud, and disquieting, are in their way the boldest statement of intent that 1975 had to offer.