For decades, Philadelphia radio legend J. Michael Harrison has brought a delightfully freeform approach to Temple University’s WRTI. In the mid-90s, I was a teenage devotee of Harrison’s show “The Bridge.” On Friday nights I’d fill up 90-minute TDK cassettes with Harrison’s adventurous DJ sets. Like many young people, my appetite for new music was ravenous and “The Bridge” helped school me on the radical sounds of free jazz, bebop and fusion. As a DJ, Harrison’s approach to selection was freeform without being formless. Each episode highlighted the depth and power of Black creativity with often underappreciated work from experimental Black musicians like Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra, Screaming Headless Torsos, and many more.

One night, Harrison came out of a station ID and introduced a song I’d never heard before, Terry Callier’s “Dancing Girl.” I was immediately drawn in by the somber, minor key guitar motif of the song’s intro. By the time Callier entered – his voice richly textured and distinctive – I was sold. As the song went along, the simple, evocative folk tune surprised me even more, unfolding into a nine-minute epic that offers a glimpse of the indomitable spirit of Black creativity.

Listen to Terry Callier’s “Dancing Girl” now.

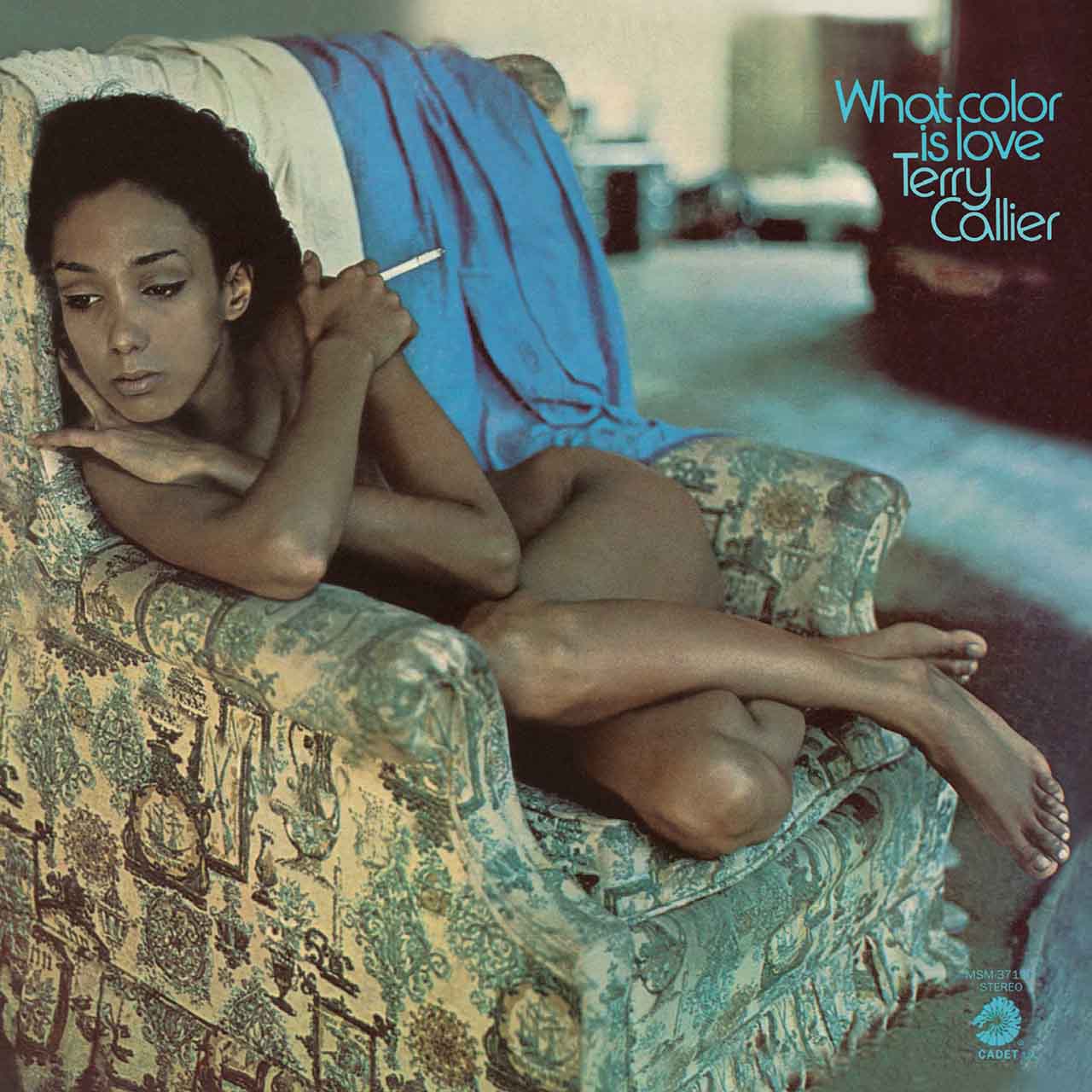

Originally recorded in 1972 for Callier’s brilliant sophomore album, What Color Is Love?, “Dancing Girl” is one of the most ambitious album openers of its time. At this point, Black artists like Isaac Hayes, The Temptations, and Curtis Mayfield were already experimenting with lengthy, extended vamps. “Dancing Girl,” however, was built on a complex, suite-like structure that allows the song’s themes and imagery to shift along with the music. In a 2007 interview with David Hollander, Callier spoke about the album’s construction. “[Producer] Charles [Stepney] had a larger concept, and so some of the tracks had anywhere from 25 to 30 musicians.”

Callier’s opening verse and chorus could be simply read as a dream about a lover in motion, but a closer examination suggests that the dancing girl that we follow to “the quiet place” somewhere “between time and space” is the muse itself. From here, the tone shifts dramatically. Callier pulls us deep into the bowels of despair where creativity cannot heal the real-life scars left by a life lived in poverty, depression, and addiction. With his voice booming and shaking at the edge of breaking, Callier references Charlie Parker, framing the jazz legend’s heroin addiction as the dark and tragic flipside of Black creative ecstasy:

Meanwhile in the ghettos dust and gloom.

Bird is blowin in his room.

All those notes wont take the pain away.

And you’ll surely come to harm,

With that needle all up in your arm.

And dope will never turn the night to day.

Released at a moment when Issac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield, and Stevie Wonder were all experimenting and pushing against the thematic and formal boundaries of soul music, “Dancing Girl” remains one of the high artistic achievements of the early 1970s. Even when we are left to languish in the worst socioeconomic conditions, we are able to thrive creatively. Despite all of the bittersweet joy and outright pain that comes with being Black in a world shaped by anti-blackness, the muse remains.

Tell her what you wanna do.

Boogie, bop or boogalo?