The first blast of New Wave in the late 1970s mostly stuck to the same rhythms that rock had revolved around for decades. But by the early 80s, US and UK bands were finding a fresh feel by assimilating sounds from Africa, India, Asia, and beyond. From big names with an international itch to under-the-radar innovators, the era was awash with worldly new ways to rock.

Jamaica was among the first nations outside the US or UK to impact the New Wave explosion, especially in England. The galvanizing rhythms of ska were jacked up with punky energy for a new generation by the burgeoning Two Tone movement, as bands like Madness, The Specials, The Selecter, and The Beat began releasing records in 1979.

The steady-rolling, deep-down sounds of roots reggae infiltrated British rock even earlier, via the reggae/New Wave collision of The Police. “Playing reggae licks to us is like blues licks, they’re hard to resist,” drummer Stewart Copeland told Trouser Press’s Jim Green in 1979. Copeland had come off a stint with prog rockers Curved Air, while Sting and Andy Summers had experience with everything from jazz to psychedelia. The British punk boom inspired them to explore new territory, though, and trading old-wave ideas like blues rock for a Jamaican influence turned out to be the perfect path.

On their 1978 debut LP, Outlandos d’Amour, bottom-heavy reggae grooves drove hits like “So Lonely,” “Can’t Stand Losing You,” and the band’s breakout smash “Roxanne.” But the band took the idea of culture-blending even further on “Masoko Tanga,” where Sting sings in a language of his own devising over a throbbing heartbeat that blends funk, reggae, and Afropop. In years to come, The Police’s pancultural pop vision would include everything from the French lyrics of “Hungry for You” to the African-informed polyrhythms of “Walking in Your Footsteps” and “Miss Gradenko.” By 1979, The Slits were at the table too, adapting dub reggae and funk to give post-punk a new gait on Cut.

Across the Atlantic, Talking Heads were combining a DIY lexicon and African ideas too, on “I Zimbra” from 1979’s Fear of Music. They would go full-bore on the African influences with 1980’s Remain in Light.

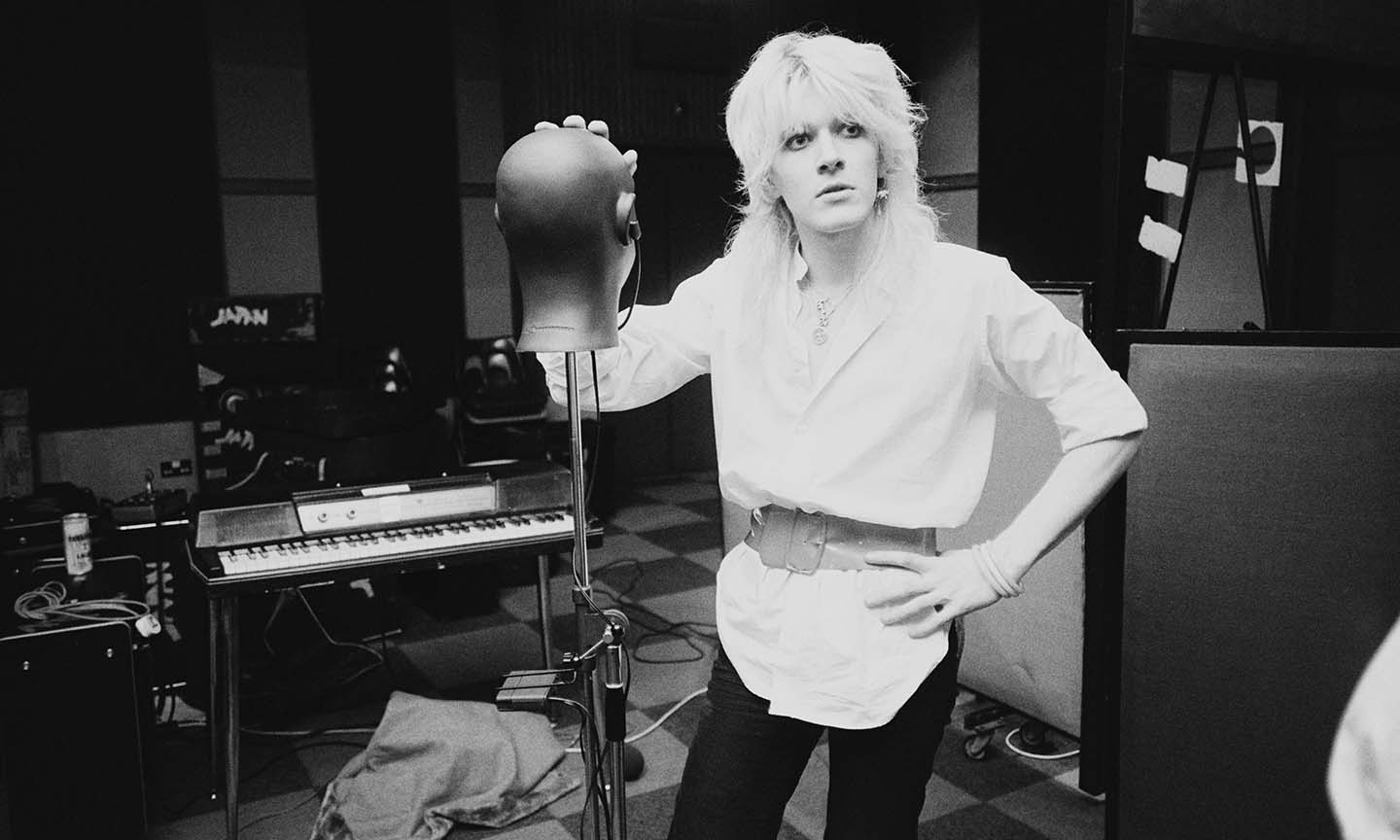

Back in England, the band fortuitously named Japan was trading its glam-rock roots for sounds evocative of the Far East. On 1980’s Gentlemen Take Polaroids, the influence of Japanese synth-pop pioneers Yellow Magic Orchestra came to the fore, with YMO’s Ryuichi Sakamoto turning up to pitch in. Drummer Steve Jansen’s pan-ethnic approach to rhythm, fretless bassist Mick Karn’s snaky, syncopated lines, and the Asian-tinged synth colors of David Sylvian and Richard Barbieri converge in a sleek, modernist exotica on songs like “Swing” and “My New Career.” As the tongue-in-cheek imperialism of its title implies, “Taking Islands in Africa” finds space for a subtle African rhythmic undercurrent. The band would bring Asian flavors even further forward on 1981’s Tin Drum.

Peter Gabriel’s solo work had come far closer to New Wave than to the prog pastures of his old band, Genesis. And the 1980 installment in his string of self-titled albums (the one with the melting-face cover) found him edging slowly toward the globalist approach that would eventually become central to his work. The percolating marimba line driving the paranoia of “No Self Control” evokes the interlocking percussive patterns of Balinese gamelan music. And years ahead of Paul Simon’s Graceland, the game-changing anti-Apartheid anthem “Biko” excerpts recordings of South African folk songs and finds Gabriel’s old bandmate Phil Collins approximating African percussion with a Brazilian surdo drum. Gabriel would become even more of a cultural magpie on his next, similarly untitled album.

Before 1980 was out, even bands best known as straight-up rockers were onboarding international influences. XTC’s stock in trade up to that time had been a hurtling power-pop/New Wave attack, but drummer Terry Chambers always had idiosyncratic ideas about breaking up the beat. And on Black Sea tracks like “Living Through Another Cuba” and “Burning with Optimism’s Flames” he pushes things along with what feels like a mashup of rock, African, and Latin American rhythms. Next time around, on the eclectic double LP English Settlement, XTC would venture further afield, with the loopy, Latin feel of “Melt the Guns” and the sub-Saharan shimmy of “Snowman” and the aptly titled “It’s Nearly Africa.”

Speaking of African influence, the end of 1980 also saw a turf battle over the use of Burundi drumming in a post-punk pop setting. It began when Adam & The Ants went through a lineup change and a style shift from punk to an unprecedented blend of New Wave, glam, Ennio Morricone-isms, and those bustling Burundi-style drums. When Adam disconnected from former Sex Pistols svengali Malcolm McLaren, the latter responded by luring the band away from him and pairing them with Burmese-English teen singer Anabella Lwin in the rhythmically similar Bow Wow Wow. Adam and his new Ants’ Kings of the Wild Frontier retained the edge, but their rivals’ debut single, “C30 C60 C90 Go,” a celebration of taping music off the radio, remains a righteous banger.

By 1981, danceability was an increasing demand for new UK bands, and imported influences were de rigueur. Alongside the acres of post-punk funkateers, the British charts sported the salsa-saturated sounds of Blue Rondo a la Turk and Modern Romance skirting the New Romantic scene, the Latin/African/jazz-funk amalgam of Pigbag, and plenty more. Meanwhile, English/American partnerships like the revamped, Gamelan-savvy King Crimson and the Middle Eastern- and African-sampling David Byrne and Brian Eno were breaking brainy-but-funky new ground.

India started getting its licks in on the British scene right around the time Punabi folk-pop was becoming a UK phenomenon with the likes of the band Alaap. Synth-poppers Blancmange had their biggest UK hit with 1982’s “Living on the Ceiling,” powered by a seemingly bhangra-inspired riff. Monsoon, fronted by Indian-English singer Sheila Chandra, scored a British hit with their bewitching debut single, “Ever So Lonely.” Their debut album, Third Eye is a heady-but-propulsive blend of Indian pop, raga, New Wave, and a splash of psychedelia. Monsoon brought things full circle by shining a different light on one of British rock’s earliest Indian-influenced milestones, The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

Even America was getting in on the action, sometimes with help from a transplanted Brit. After relocating to New York City, the mercurial Joe Jackson found fresh inspiration in the local Latin music scene. He funneled that energy into a total retooling of his sound, abandoning guitars entirely and making Latin piano vamps and salsa percussionist Sue Hadjopoulos an integral part of his new style.

“There’s current music which isn’t rock ‘n’ roll,” Jackson reminded Musician’s David Gans in 1983, “all the great jazz, Latin music, and funk that’s going on in New York. Who needs rock ‘n’ roll?” Night and Day became Jackson’s biggest album. The fusion of Nuyorican and British musical mindsets shines brightly on the transcendent “Another World,” where Hadjopoulos’s timbales and Jackson’s piano contrast with dreamlike lyrics for one of the most affecting pieces in the singer’s catalog.

Tim McGovern, guitarist for The Motels, was searching for something new too, having left the band before their ascent to stardom. In Los Angeles, he formed Burning Sensations, putting together a potent cocktail of Latin, African, and Caribbean elements, New Wave, and psychedelia. Their island-breezy single “Belly of the Whale” got some attention but they only lasted long enough for an EP and one album.

Unfortunately for Burning Sensations and other adventurous Yanks, worldbeat influences weren’t fully embraced in the US mainstream until at least the mid-’80s. But earlier in the decade, rockers liberated by punk found new paths to freedom by opening their ears to the rest of the globe. It made for some incredible music.