For Mississippi’s David Banner, rapping felt like God’s path. When his beloved van where he often made music was stolen, the thieves threw the master copies of an album Banner was working on out the window before leaving. When Banner came to find his van gone, he found the CD and knew it was a sign. That sense of mission can be found throughout his major label debut, Mississippi: The Album. Banner knew he had to get it right. He knew he had something important to say.

Just look at the video for the album’s massive club hit “Like A Pimp,” which opens with Banner running through a cemetery with a tattered Confederate flag draped around his body, presumably escaping a lynching. (A noose can be seen ominously hanging behind him.) Interspersed amongst clips of Banner crowd surfing and people dancing, there are darker shots of Klansmen protecting their crosses, which Banner and his crew destroy. While the modern-day definition of “conscious rap” may wag a finger against strip club anthems and sex songs, Banner and his Southern counterparts found a way for all messages to coexist.

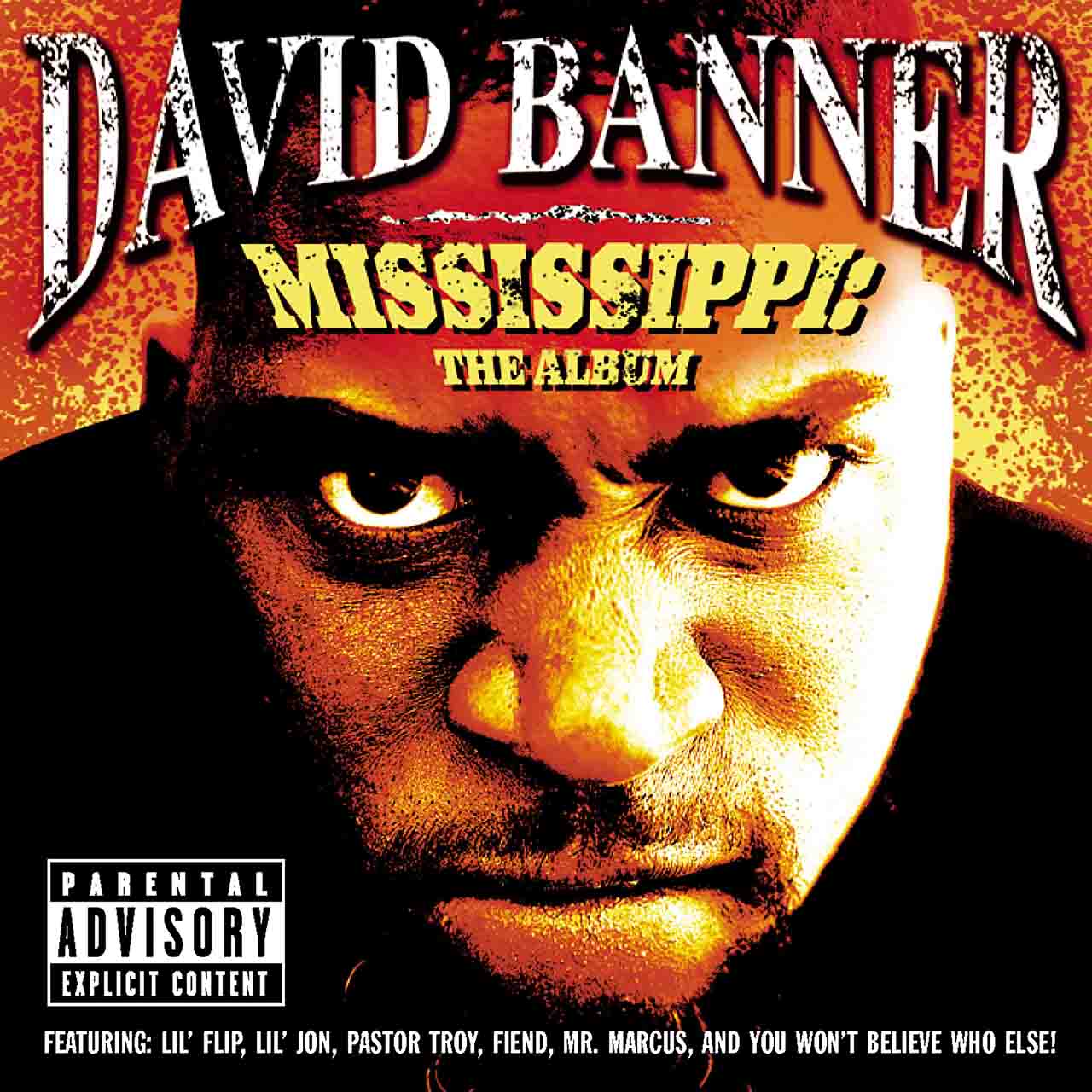

Listen to David Banner’s Mississippi: The Album now.

On Mississippi’s first single “Cadillac on 22’s,” he makes an impassioned plea to God to forgive him and his state. “Maybe hell ain’t a place meant for us to burn/ Maybe Earth is hell and just a place for us to learn,” he raps over an acoustic guitar. Mississippi is the state with the most recorded lynchings, and Banner opens the second verse with the lines, “Lord they hung Andre Jones/ Lord they hung Raynard Johnson.” For 18-year-old Jones, a traffic stop in 1992 ended in tragedy when he was found hanged in his jail cell. The 17-year-old Johnson was found hanging from a tree in his front yard in 2000. Both deaths were officially ruled suicides.

In the video for “Cadillac on 22’s,” Banner positions himself as a healer. He approaches a young girl in a casket, bringing her spirit back to life. He zaps other people back into consciousness as he marches down the street with a growing crowd, including a man in a stretcher and a car crash victim. He even comes face-to-face with Jones and Johnson, both standing in front of nooses with fear in their eyes. With the help of the young girl, Banner facilitates a safe, peaceful transition for the restless souls of the young men, imagining a better outcome and rewriting Mississippi’s complicated history.

Banner saw Mississippi as a way to position himself as deity-like, the patron saint of a state that continues to grapple with its complicated history. From the sanctity of the club to the brutality of the streets, Banner commanded respect. Sonically, while giving nods to the ever-present ringtone rap of the era, he also found a way to look to the past, crafting African-American folk and gospel songs for a new generation. Even on the album’s most subdued tracks, Banner’s gravelly bark demands space, each song another act in his impassioned sermon.

Across the album, his country twang and subtle Mississippi blues influence give the album a rugged charm. Banner’s soulful, maximalist production shines, whether it be the sultry guitars and whispery percussions on “My Shawty” or the speaker-breaker “Bring It On,” the latter of which deserved the same caution tape as Three 6 Mafia’s “Tear Da Club Up.” The biggest subject of the album, however, is Mississippi itself. Unlike a lot of rappers, Banner’s palpable hunger and anger wasn’t that of someone who wanted to “make it,” but rather the passion of someone who wanted the world to know that Mississippi existed at all. In an interview with the Jackson Free Press ahead of the album, journalist Donna Ladd asked why Banner still loved Mississippi despite its painful history, to which he poignantly replied, “Love is almost a direct synonym for pain; the only reason you love something is that you’re fearful of the fact that it might go away.”

Ever since the release of Mississippi, Banner has become an outspoken activist for civil rights. He became involved in the campaign to change the Mississippi state flag. (Its previous iteration was emblazoned with the same Confederate flag he’s taken every chance to burn, dancing in its ashes.) He’s been decorated with awards for his humanitarian relief following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. He’s even testified in front of Congress on behalf of hip-hop, powerfully stating, “If by some stroke of the pen hip-hop was silenced, [these] issues would still be present in our communities.”

For Banner, though, it all started here, with Mississippi. It’s a record worth hearing again (or for the first time) to truly understand what drives him today.