In 1998, hip-hop was in crisis. Biggie and Tupac had been killed in 1996 and 1997, respectively, and the throne sat empty. Meanwhile, the shiny suits and 80s inspired pop hits of Sean “P. Diddy” Combs’ baited the mainstream in ways not seen since the days of M.C. Hammer.

Into that commercial climate stepped DMX. Born Earl Simmons in Yonkers, NY, X spent his early years in and out of prison while besting local MCs in rap battles. Personal demons aside, the kid had talent, and in 1991, his demo tape landed him in the ‘Unsigned Hype’ section of The Source. A year later, he dropped a poorly-promoted single, “Born Loser” on Ruffhouse Records and then beat a pre-fame JAY-Z in a Bronx rap battle (the pair would later collaborate with Mic Geronimo in 1995 on “Time To Build”).

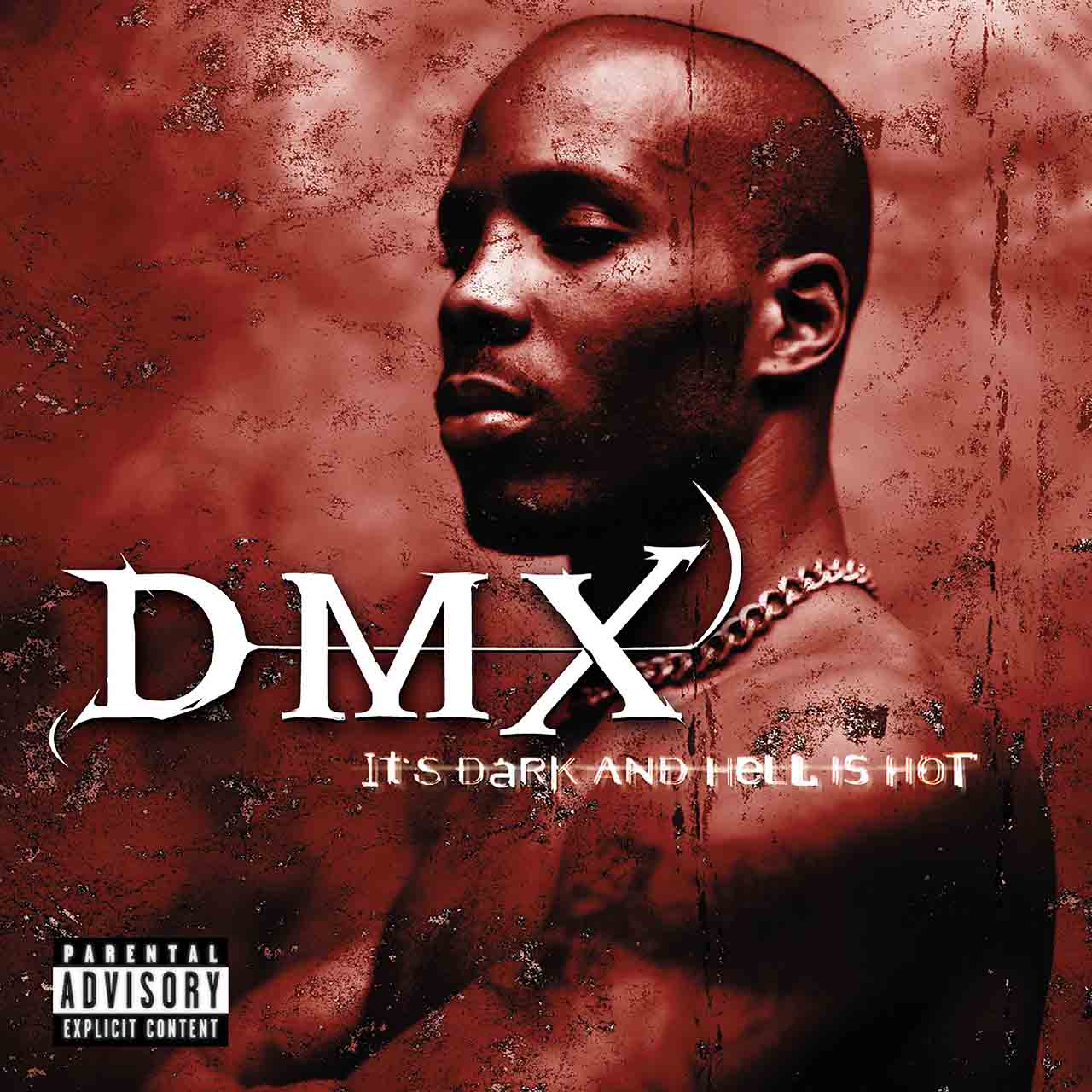

Listen to the DMX album It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot now.

Still, labels like Bad Boy and TVT passed on signing him – not marketable enough, they said. In the interim, he went back to robbing and stealing. But it wasn’t until 1997, when Def Jam execs Lyor Cohen and Kevin Liles traveled to Yonkers to hear X rap with his jaw wired shut (he’d been the victim of a savage beatdown in his neighborhood) that he was offered a contract. “Lyor [was] giddy with excitement,” Irv Gotti, then an A&R at the label, remembered in an interview with XXL. “His exact words to me [were]: we have the pick of the litter.”

By January of 1998, guest spots with LL Cool J (“4, 3, 2, 1”), Mase (“24 Hours To Live”), and Cam’ron (“Pull It”) earned the Dark Man X serious buzz. But it was when Funkmaster Flex began dropping bombs on his first official single “Get At Me Dog,” that X truly arrived. Over a sparse B.T. Express sample, X rapped: “What must I go through to show you shit is real / And I ain’t really never gave a fuck how niggas feel / Rob and I steal, not cause I want to cause I have to / And don’t make me show you what the MAC do.”

All angst and pent-up aggression, if hip-hop had been one big party, “Get At Me Dog” was the stick-up outside. That was by design – “I wasn’t down with all that pretty, happy-go-lucky party shit,” DMX said in E.A.R.L: The Autobiography of DMX. “I couldn’t hate on what Puff was doing, but I wasn’t with it…I made a promise to myself that I would not take my audience to the wrong place. I didn’t wait all this time to get put on to sell myself out now.”

A second single, “Stop Being Greedy,” soon followed. On it, X pleads: “Ya’ll been eatin’ long enough now, stop being greedy / Just keep it real partner, give to the needy / Ribs is touchin’, so don’t make me wait / Fuck around and I’m gon’ bite you and snatch the plate.” Again, it portended change. “[There are] a lot of wack motherfuckers out there right now killing the charts,” X said. “I’m telling them to stop being greedy. I’m saying let some brothers who are actually talented get some of this money.”

With both songs booming on the radio, mixtapes littered with freestyles, and guest appearances galore (The Lox “Money, Power, & Respect” peaked at No. 1 on the Top Rap Songs Chart), anticipation couldn’t have been higher for X’s first album, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot. And when the LP hit stores on May 12, 1998, it quickly shot to No. 1 on the Billboard 200, eventually moving more than four million units.

But the story of It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot wasn’t the sales, since multi-platinum albums were commonplace back then; rather, it was the content. Here was a rapper bucking all trends, not aiming for airplay or wowing with witticisms. The only thing that DMX was selling was himself – every dark corner of his mind, every crime he’d committed, and every hard lesson he’d learned. He was a jailhouse poet spitting street corner philosophy, and it worked.

X’s tug of war with the light and the dark is heard throughout the album. Songs like “Look Thru My Eyes,” “Let Me Fly,” and “X is Coming,” are haunting odes to the demons tearing Earl Simmons apart from within. On “Damien,” X is goaded into a series of bad decisions by an ill-intentioned guardian angel; on “The Convo,” he talks to God directly, confessing it is he whom he must thank for everything, including the bad things.

Even the album’s highlight, “Ruff Ryders Anthem,” is deceptively introspective, with X suggesting, through growls and barks, that in America, he is more than a caged beast (“a slave until my home is a grave”). Meanwhile, X shouts his call-and-response hook (“Oh, no, that’s how Ruff Ryders roll”) over producer Swizz Beats’ synthesizers and stuttering drums – a radical backdrop at a time when hip-hop was built over sampled loops and steady 4/4 grooves.

“DMX didn’t want to do it,” Swizz Beats told Complex. “He was like, ‘Man, that sounds like some rock ‘n’ roll track, I need some hip-hop shit. I’m not doing that. It’s not hood enough.’ I told him, ‘Yo, we can make it hood!’ And then my uncles [Darrin “Dee” Dean and Joaquin “Waah” Dean who ran Ruff Ryders] said, ‘Yo, we should step out the box a little bit.’ We bugged him and bugged him to do this shit. Then he came in and did it, and we were just hyping him up. The ‘What!’ ad-lib and all of that came about in the middle of us hyping him up. We left it in the track to add energy… It was his best shit at that time.”

Within months, “Ruff Ryders Anthem” had become X’s signature jam, the album’s “Intro” was fight music, literally – Mike Tyson entered the ring to it before knocking out Francois Botha – and there was another album, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, going Platinum (the first time two Platinum albums by one artist had been released in less than a year). The Hype Williams-directed film Belly followed in 1999, which lead to a series of Hollywood action flicks.

X was one of the biggest stars in the rap game until at least the mid-aughts, when legal issues and drug addictions got the best of him. But in 1998, no star burned brighter than his. He had wrestled hip-hop from the manicured hands of those who then controlled it, brought it back to the streets where, for years, it remained. And it all started with It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot.