“Oye La Noticia,” the explosive opener from Ray Barretto’s 1970 album Barretto Power, starts with the low rumble of conga drums – a quick, barely-there flourish that sets the stage for the ferocity that Barretto eventually unleashes. The song stands out as one of the most forceful on a record that reaffirmed Barretto’s place as a masterful and versatile drummer. Softer moments on the album – including the smooth “Perla Del Sur” and the bolero-style romance of “Se Que Volveras” speak to Barretto’s subtle hand, but “Oye La Noticia” is a formidable declaration. “To the envious one who wants to see me on the floor, I give you news once more that I’m here,” the Puerto Rican crooner Adalberto Santiago sings, memorably announcing Barretto’s intentions with Barretto Power.

Barretto was born in New York City, but he fell in love with bebop music in Germany. (He enlisted in the Army in 1946 at the age of 17.) His love of music led him to teach himself to play the conga drum once he left the service. “I got my first congas from a bakery on 116th Street in Harlem that used to import drums from Cuba,” Barretto told JazzTimes, adding, “I used to take those drums and put them on my shoulder and get on the subway, and anywhere between 110th Street and 155th Street in Harlem there were places to jam every night. I spent three, four years just going to jam sessions. It turned out to be the best thing I ever did. I met Charlie Parker, Dizzy, Max Roach, Roy Haynes, and Art Blakey.”

Listen to the best of Ray Barretto on Apple Music and Spotify.

In 1961, he landed his first hit with the song “El Watusi,” which reached no. 17 on the Billboard charts. Rather than aim for another blockbuster track, however, Barretto signed with Fania Records in the late 1960s and went down a decidedly experimental route. His label debut, Acid, turned boogaloo on its head by mixing it with rock, jazz, and soul. The follow-up, Hard Hands, featured a more street-style approach to percussion, while 1969’s Together showcased the tightness Barretto could achieve with a band. Each of these records proved Barretto’s ability to effortlessly meld sounds. But it’s on Barretto Power that the full extent of his versatility became clear.

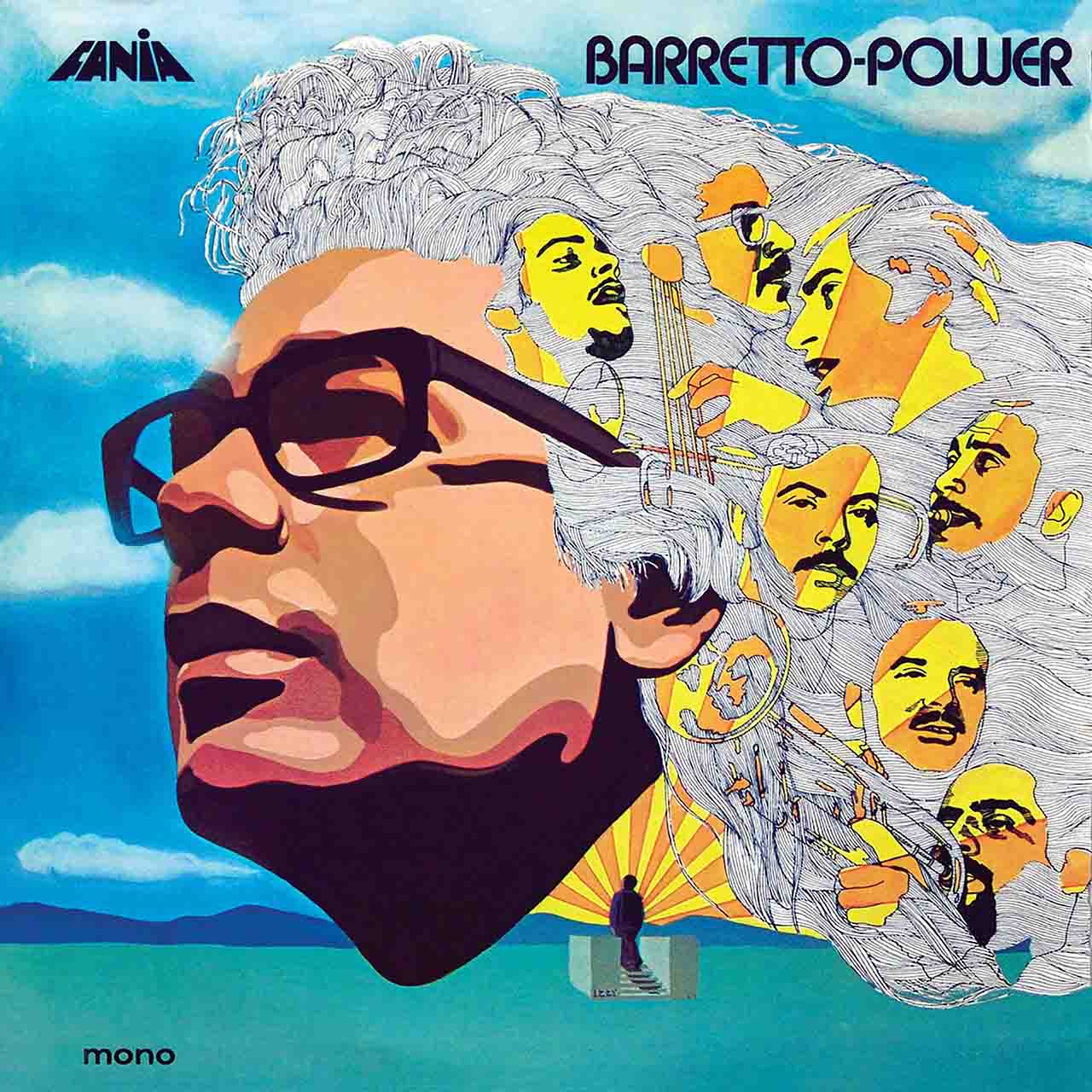

Barretto Power came out late in 1970, an interesting time for Fania Records. Fania had been around for six years, and was refining its approach. That explains, in part, why the cover for Barretto Power was more polished, made up of a slightly retro image that shows Barretto’s band strewn into the conguero’s hair. The image is both psychedelic and immaculately arranged, qualities that speak to the precision of the music played by a band that effortlessly riffed on the Cuban conjunto sound. The record includes Andy González, the young, Bronx-born bassist, as well as Louis Cruz on piano, Tony Fuentes on bongos, and Orestes Vilató on timbales. Papy Roman, René López, and Roberto Rodríguez energized the album with their trumpets, adding boosts of energy on “Quítate La Máscara” and a dreamy, almost throwback quality on smoother cuts, such as “Perla Del Sur.”

Bubbling under the surface of all this was a defiant, righteous spirit that mirrored the time period. In a 2019 feature for JazzTimes, Bobby Sanabria remembers that Barretto could sometimes be found “at a rally protesting some injustice,” and Barretto Power offers a glimpse into how engaged he was. “Right On,” for instance, is an understated empowerment anthem, its trumpets blaring out like a fist in the air.

As forward-thinking as Barretto was on Barretto Power, he constantly embraces tradition as well. This may seem surprising, given his avant-garde flourishes, but it was a point of pride. Barretto was constantly looking back at history and reminding both Nuyoricans and other Latin musicians of the wealth of sounds they’d inherited. Perhaps it’s why songs such as “De Qué Te Quejas Tú” have a slight old-school flair. “Y Dicen” and “Se Que Volveras” continue the album’s classic streak and show how tenderly Barretto could produce clear-eyed, timeless salsa.

Barretto’s experimental impulses come surging back for the closer “Power.” A piano melody starts the song off gently, almost as though it’s stirring the band awake. Then, a few seconds in, Barretto begins hammering out a percussion rhythm, bringing the energy up and preparing listeners for a choir of trumpets that blare out enthusiastically.

“Power” is six minutes long, ducking in and out of impressive improvisations, and it serves as a proud display of Barretto’s power as a conguero and a musician. It also feels like Barretto is urging his fans to take some strength from his playing and to remember their own power. Perhaps that’s why the album still resonates today, providing a soundtrack for people working to make their voices heard. In the end, Barretto Power lays bare all the things that the master conguero stood for: a love of tradition, a chameleonic approach to music, and an enlightened progressiveness.