James Brown was the summation of Black American culture in musical form. “Mr. Dynamite” sat at the forefront of soul and funk, laid a rhythmic foundation for everything from disco to hip-hop, and inspired everyone from Fela Kuti to Marley Marl. But there was something beyond James Brown’s impassioned grunts and gritty grooves; James Brown was more than a hitmaking musical innovator and electrifying performer. He symbolized an energy and an aura of Blackness that transcended music. Brown’s music, approach, and persona spoke to the rising tide of Black pride, making him a seminal socio-political figure – even as his politics evolved, shifted, and even sometimes confused his fanbase.

Watch Funky President, episode two of Get Down, The Influence of James Brown, below.

James Brown’s music was always a cultural force. Early singles like “Please Please Please” and “Try Me” showcase a brand of gutsy soul that heralded the sweatier branch of R&B’s family tree, one that would soon yield fruit from Stax Records and Muscle Shoals. From the mid-60s on, Brown’s proto-funk classics set the stage for everyone from George Clinton to Sly Stone, opening the floodgates for an aggressive and loose take on Black music that seemed to coincide with a freeing of Black consciousness – no longer beholden to crisp suits and smiling publicity photos.

James Brown’s politics in the 60s

As popular music became increasingly political in the late 1960s, James Brown’s status became even more obvious, he flexed considerable weight as a community force and a cultural influencer before such parlance had entered the lexicon.

His approach was refreshingly direct. He released “Don’t Be A Drop-Out” in 1966, with high school dropout rates on the rise. He was also an outspoken supporter of the Civil Rights Movement throughout the 1960s. He performed charity concerts for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; and he headlined a rally at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, during the “March Against Fear” begun by James Meredith, who was shot early in the outset of the march. Meredith had famously been the first Black student to attend the University of Mississippi in 1962, accompanied by the National Guard.

Brown had tremendous sway with a generation, and he understood his power. How he applied that power reveals a complex man who was undoubtedly one of principle, no matter how unfashionable those principles may have appeared. In 1968, Brown released the pointed “America Is My Home”; the song was Brown’s response to anti-Vietnam sentiments expressed by Black leaders like Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King, Jr. The song evokes a sense of togetherness even in the face of frayed times, and highlights Brown’s almost old fashioned brand of patriotism.

“Some of the more militant organizations sent representatives backstage after shows to talk about it,” he wrote in his autobiography. “‘How can you do a song like that after what happened to Dr. King?’ they’d say. I talked to them and tried to explain that when I said ‘America is my home,’ I didn’t mean the government was my home, I meant the land and the people. They didn’t want to hear that.”

His sense of American pride sat in tandem with his staunch support of Black issues and in late 1968, he issued his most famous and most enduring tribute to Blackness. “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” announced “Black” as a term of pride and identity, flying in the face of white supremacy and the self-loathing it had wrought in so many Black people. In interviews, Brown made it clear that he was pushing against the old idea of “colored” and towards something more empowering in “Black” assertiveness.

James Brown’s legendary Boston concert

That same year, the cultural influence of James Brown came into sharp relief during a now-legendary concert in Boston. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., American cities erupted in violence and outrage. Brown was scheduled to perform in Boston, but the city was considering canceling the show due to the unrest. There was concern, however, that cancellation would only fuel the simmering hostilities. It was decided at the last minute that the show would be broadcast live, with city officials nervous that none of this would be enough to quell a riot.

Brown took the stage praising city councilman Tom Atkins for bringing it all together in spite of the climate. The audience who showed up for Brown’s concert was significantly smaller than anticipated (approx. 2000 instead of the expected 14,000 attendees), and the show was broadcast live on WGBH in Boston.

Brown didn’t just masterfully calm the crowd that night, he kept law enforcement in line as well. When fans tried to rush the stage and officers acting as security, drew nightsticks, Brown urged them to calm down. Brown’s concert and the broadcast were credited with keeping Boston calm on a night when most American cities were still burning. The night solidified Brown’s status both within the community and to outside observers. The performance would eventually be released as Live At the Boston Garden: April 5, 1968, and the subject of a documentary called The Night James Brown Saved Boston.

The 70s and beyond

James Brown’s perspective was one of perseverance but he also had a penchant for “up from your bootstraps” sermonizing. “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get It Myself)” was a dedication to Black self-sufficiency that seemed to sidestep systemic racism. And, as the 60s gave way to the 70s, James Brown’s politics seemed to become more complex – even contradictory.

On one hand, he’d tell Jet magazine that he couldn’t “rest until the black man in America is let out of jail, until his dollar is as good as the next man’s. The black man’s got to be free. He’s got to be treated like a man.” And he spent a significant amount of time in Africa. At the invitation of President Kenneth Kaunda, he would perform two shows in Zambia in 1970; he famously took the stage at Zaire 74, the concert festival in Kinshasa that predated the famed 1974 “Rumble In the Jungle” fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. The following year, he performed for Gabonese President Omar Bongo’s inauguration. He believed in the bond across the African diaspora, and he was a vessel for that connection; he praised the culture of Zambia and directly influenced Fela Kuti’s brand of 70s Afrobeat.

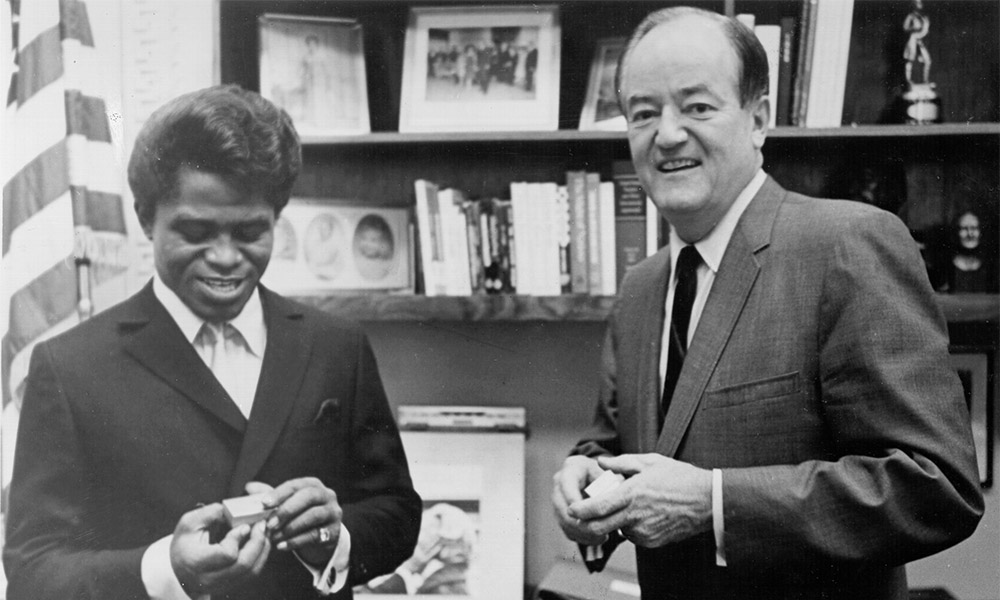

On the other hand, Brown’s politics grew more and more confusing to his fanbase. There were several controversial moments in the decades following, including the embrace of various conservative figures. Brown’s feeling about it was simple: It was important to be in dialogue with those in power.

Ultimately, James Brown’s politics were a reflection of himself; a Black man who’d risen to superstardom out of the Jim Crow South; who’d seemed to embody the idea that he could achieve anything with hard work and a little bit of ruthlessness. His pride in his people was obvious in his music and in his activism; it was just as obvious that his belief in self-sufficiency seemed to cloud his take on oppressive realities. His anthemic classics are odes to Black expression and Black affirmation; and his legacy is evidence of the tremendous power in both.