MC Hammer’s career arc is one of extremes. The Bay Area legend’s meteoric rise in the late 1980s was the crescendo of hip-hop’s first push into the pop culture mainstream – a trend that had been growing in earnest since Run-D.M.C.’s debut in the mid-’80s, continued through the success of Def Jam artists like LL Cool J and Beastie Boys, and was galvanized by the debut of popular rap video shows like Yo! MTV Raps and BET’s Rap City. Hammer’s blockbuster 1990 album Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em made him one of the biggest stars in the world. His popularity in the aftermath of that album’s success has been well-documented, but Hammer’s legacy didn’t begin with Please Hammer… and the ubiquitous “U Can’t Touch This.” And it doesn’t end there, either.

Listen to MC Hammer on Apple Music and Spotify.

Growing up in a small apartment in Oakland, California, Stanley Burrell loved James Brown. “I saw James Brown’s appearance at the Apollo on TV when I was three or four years old and sort of emulated it,” Hammer told Rolling Stone in 1990. “I did the whole routine of ‘Please, Please, Please,’ falling to the ground and crawling while my brother took a sheet and put it over my back as a cape.”

Burrell’s talents were immediately evident. He wrote commercial jingles for McDonalds and Coca-Cola as a hobby, and performed for fans in the Oakland Coliseum parking lot. When Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley saw the 11-year-old Stanley dancing, he offered the kid a job. Young Burrell’s stint as the A’s batboy would prove fortuitous in many ways: he famously got his nickname “The Hammer” from baseball great Reggie Jackson who thought he looked like “Hammerin’” Hank Aaron, and years, later, the A’s would play a major role in helping Hammer to get his burgeoning music career off the ground.

Hammer’s initial dream, in part due to his A’s lineage, was a pro baseball career. He tried out for the San Francisco Giants after high school, but his bid for Major Leagues was unsuccessful. So was his time studying for a communications degree. He pondered turning to drug dealing, but ultimately decided on a stint in the Navy, and turned his attention towards his faith. Christianity became a major influence in Hammer’s life, and he formed a gospel rap group called the Holy Ghost Boys that went nowhere, despite some interest from labels.

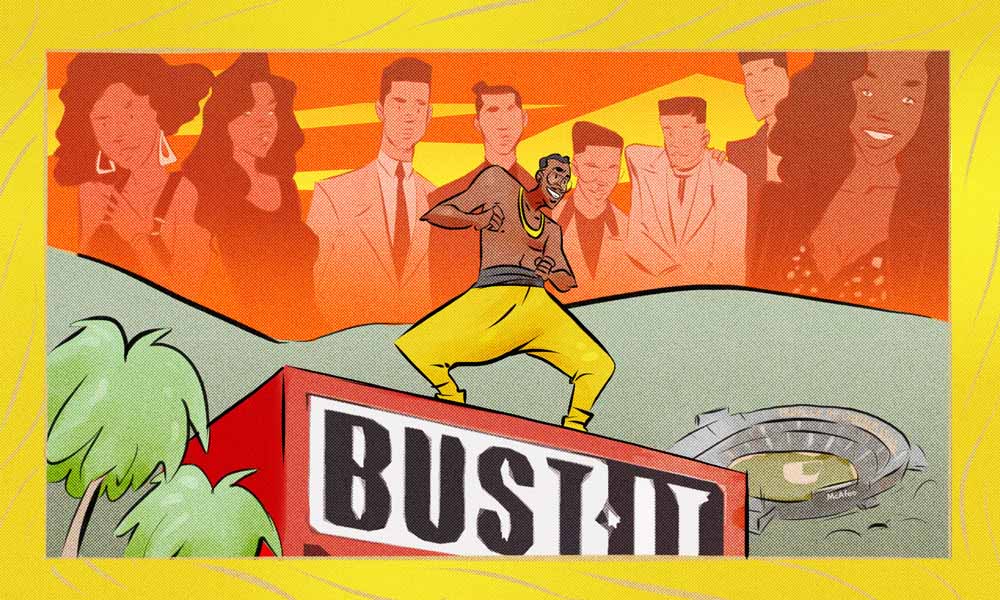

Determined to take his destiny into his own hands after Holy Ghost Boys broke up, Hammer set about launching his own company, Bust It. He went to the streets and began recruiting rappers, DJs, and dancers. Kent Wilson (Lone Mixer) and Kevin Wilson (2 Bigg MC) became his DJ and hypeman, respectively; Hammer tapped Suhayla Sabir, Tabatha Zee King-Brooks, and Phyllis Charles to be his background dancers (dubbed Oaktown’s 357) and set about pushing himself and his affiliates to greater, wider success. Hammer was demanding and focused, leading marathon rehearsal sessions to push his act to a higher place. ”We try to keep our organization disciplined because we have goals,” he told Rolling Stone. “And in order to achieve those goals we must be disciplined.” Hammer’s approach echoed his idol James Brown, who was famously demanding of his band and backing vocalists. For so many legendary Black performers of that era, excellence was a prerequisite.

Armed with a $20,000 loan from Oakland A’s outfielders Dwayne Murphy and Mike Davis, Hammer founded Bust It and, in 1986, recorded his first official single, “Ring ‘Em.” By the follow-up single, “Let’s Get It Started,” he began to get local mix-show spins. Hammer partnered with Felton Pilate, frontman, instrumentalist, and producer of the recently disbanded Con Funk Shun, and recorded his first full-length album – and the first in a long collaborative relationship – in Pilate’s basement studio. In August of 1986, Bust It released MC Hammer’s debut LP Feel My Power. The rapper and his wife Stephanie pushed the album to local DJs relentlessly. With the couple working as Bust It’s promo team, Feel My Power sold an impressive 60,000 copies, and Capitol Records took notice.

Capitol was eager to break into the hip-hop market and, in Hammer, they saw an explosive showman who already had a built-in business model. Hammer signed to the label in a reported $10M joint venture with Bust It, and he invested his $750,000 advance back into his label. Capitol revamped and re-released Feel My Power in the fall of 1988 as Let’s Get It Started, and singles “Turn This Mutha Out” and an updated “Let’s Get It Started” were major hits on the Rap Charts. The LP sold 1.5 million copies, and Hammer became one of the hottest commodities in hip-hop.

He hit the road to support the release, and brought his entire roster on the tour, along with hip-hop heavyweights like Tone Loc, N.W.A., and Heavy D & the Boyz. He outfitted a recording studio in the back of his tour bus, ensuring that time on the road wouldn’t take away from working on music.

With his solo career in high gear, Hammer pushed Bust It into the spotlight. Between 1989 and 1990, the label introduced a slate of acts for every music lane. His dancers Oaktown’s 357 were up first; a sexy but confident rap group that fit alongside J.J. Fad and Salt n’ Pepa. They released their debut album in the spring of 1989, and infectious lead single “Juicy Gotcha Krazy” became a major rap hit that year. Hammer’s cousin Ace Juice – also a backup dancer – released his debut shortly thereafter, and saw limited success with the single “Go Go.”

After an appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show broke MC Hammer to an even wider mainstream audience, his popularity – and the fortunes of Bust It Records – looked primed to explode. That explosion came in the form of 1990’s monster hit single “U Can’t Touch This,” recorded in the studio on Hammer’s tour bus. The song shot to the Billboard Top 10 and the music video was one of the most played on MTV in early 1990, turning MC Hammer into a pop superstar. His second major-label album, Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em, eventually sold over 10 million copies. Hammer landed tracks on the soundtrack to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Rocky V.

At every step of the way, Hammer tried to bring his team along for the ride. The Rocky V soundtrack, for instance, had the Bust It rapper Joey B. Ellis performing “Go For It.” Meanwhile, Hammer’s backing-vocalists-turned-male-R&B-group Special Generation, adding to the abundance of New Jack groups like Hi-Five and Troop with 1990’s Pilate-produced Take it To the Floor. Pilate also produced the solo spotlight for former Oaktown’s 357 vocalist B Angie B’s 1991 self-titled album. Angie combined the style and sex appeal of her young R&B contemporaries with the more mature vocals of the Quiet Storm era.

As you might expect, Hammer’s stage show around this time was famously extravagant, with his corp of dancers, DJs, band members, and singers performing a high-energy show the likes of which had never been attempted by a hip-hop artist – with sometimes as many as 30 people onstage. Everything about MC Hammer had become bigger and bolder: the “Hammer pants” that would become his trademark were now a famous fashion trend, and Bust It was pushing to be a forerunner in popular music.

In 1991, as Hammer was gearing up for his follow up to Please, Hammer… Bust It/Capitol President (and Hammer’s brother and manager) Louis Burrell told the LA Times that the label, which had offices in New York, Los Angeles, and Oakland would expand to pop and metal by the following year. But the release of 1991’s 2 Legit 2 Quit signaled a downturn. The album sold a fraction of what Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em had, and a growing backlash against Hammer had turned into a tidal wave of dismissals. What’s more, the rest of the groups under the Bust It banner were also failing to hit.

Even as Hammer’s fortunes famously nosedived, he continued to release music through Bust It, and expanded the roster with hip-hop pioneer Doug E. Fresh, R&B group Troop, and other new acts. The music landscape, however, was shifting towards a harder sound: gangsta rap. Hammer saw commercial success with 1994’s single “Pumps In A Bump,” and Bust It would score an unexpected hit a year later with a novelty song from NFL superstar Deion Sanders called “Must Be the Money.” But despite releases from Doug E. Fresh and Troop, Bust It faded as MC Hammer filed for bankruptcy and worked to revamp his career.

Bust It Records had a relatively short shelf life, but the label’s lofty ambition was a testimony to MC Hammer’s vision and penchant for entrepreneurship. Today, it’s forgotten that Hammer aimed to seamlessly fuse hip-hop, R&B, go-go, and pop; and its cadre of artists were at the fore of both pop-rap and new jack swing at a time when rap’s push into the mainstream of pop and R&B radio was apparent. Similarly, Hammer’s fall from grace overshadows his laser-focused entrepreneurial spirit, independent success, and the sheer vastness of his presence at his peak, which included branding and business deals with Pepsi and British Knights, a self-produced movie, and a cartoon. It was nearly a decade before Master P would approach the same level of ubiquity with his No Limit empire.

MC Hammer helped make rap music mainstream, and his Bust It Records is an important moment in the history of hip-hop labels. It’s been a while since “Hammer Time,” but it’s worth remembering that he was no pop culture flash-in-the-pan – and Bust It was more than just a boutique label. This was groundbreaking stuff. And hip-hop is stronger now for it.

Black Music Reframed is an editorial series on uDiscover Music that seeks to encourage a different lens, a wider lens, a new lens, when considering Black music; one not defined by genre parameters or labels, but by the creators. Sales and charts and firsts and rarities are important. But artists, music, and moments that shape culture aren’t always best-sellers, chart-toppers, or immediate successes. This series, which centers Black writers writing about Black music, takes a look at music and moments that have previously either been overlooked or not had their stories told with the proper context. This article was originally published in 2020.