From the moment you first hit New Orleans, the city’s musical history is impossible to avoid. Fly into Louis Armstrong International Airport – the world’s only major metropolitan airport named after a jazz musician – and you’ll be greeted by a life-sized statue of the man himself. Instead of standard Muzak, you’ll hear local classics through the sound system. It could be The Meters’ “Hey Pocky Way,” Armstrong’s ubiquitous “What A Wonderful World,” or Allen Toussaint’s “Shoo Ra” guiding you toward baggage claim. If it’s lunchtime you might even find a jazz combo playing in the piano bar.

There are locals who swear that everything great about American music came from New Orleans. And, to large extent, they’ve got a point. Credit that partly to New Orleans being a seaport city, or the “northernmost point of the Caribbean” as it’s sometimes called. From the start, New Orleans music was about absorbing a world of influences and creating something uniquely funky and tasty out of it.

A shot of wild abandon

Jazz was largely spawned in the brothels of Storyville, where Jelly Roll Morton and the unrecorded Buddy Bolden casually dispensed genius to the customers. In later decades the city’s two great Louises, Armstrong and Prima, would take jazz to the world. Louis Armstrong is rightly established as the city’s (and possibly the country’s) flagship artist, laying down invaluable groundwork with his seminal Hot Fives and Sevens recordings. Even before he became the toast of Vegas, Prima combined solid jazz, Italian roots, and good old showmanship into the stuff of enduring hipsterism.

New Orleans didn’t invent rock’n’roll, but it did give it a shot of wild abandon – not least when Little Richard recorded “Tutti Frutti” at the legendary J&M Studio on Rampart Street. In the 60s, the city devised its own form of soul/R&B under the guiding hand of producer, arranger, and songwriter Allen Toussaint. The 80s brought national attention for The Neville Brothers’ funk/soul gumbo, and the brass-band revival spawned by The Dirty Dozen and Rebirth Brass Bands. And the traditions go on…

Hot alternative band The Revivalists, soulful jazz dynamo Trombone Shorty, and hip-hop ruler Lil Wayne have all absorbed the city’s musical history as well. The Revivalists can switch from a tight rocker to a free-flowing jam at will, and Shorty regularly serves up vintage funk grooves, brass workouts, and hip-hop in the same set. With his dazzling wordplay and deft rhythms, Wayne started out making bounce-inspired hip-hop – a variety of rap that’s still rooted, however distantly, in the parade chants of the Mardi Gras Indians.

From Congo Square to The House Of The Rising Sun

Music permeates the city, yet certain spots are more sacred than others. The most hallowed is Congo Square, just above the French Quarter and now part of Louis Armstrong Park. This was where slaves gathered on Sunday and, according to legend, first laid down the African-derived rhythms that have permeated New Orleans music ever since. One of the first popular composers to borrow these rhythms was New Orleans native Louis Moreau Gottschalk, whose 1844 piece “Bamboula” incorporated African syncopations and bits of a Creole tune recalled from his youth. Also characteristic of New Orleans music is the piece’s otherworldly quality. In this case because the composer, then just 15 years old, was delirious with typhoid fever when he wrote it.

There’s no getting around the fact that New Orleans owes some of its musical history to a thriving red-light district. In fact, the denizens of Storyville were some of the only people who heard jazz in its original incarnation, since Buddy Bolden – the cornetist who gets as much credit as anyone for originating jazz – never made it to the recording studio (one teenage fan of his who eventually did was Louis Armstrong). Another of the district’s musical giants, Jelly Roll Morton, wrote a few of the swing era’s cornerstone pieces, “King Porter Stomp” and “Winin’ Boy Blues” among them. One enduring artifact of Storyville is the song “Basin Street Blues,” popularized by Armstrong in 1929, a decade after Storyville was shut down. Glenn Miller and collaborator Jack Teagarden would later add lyrics that made the street sound far more wholesome than it was.

One thing you wouldn’t find in Storyville is The House Of The Rising Sun, the New Orleans brothel celebrated in a folk song that The Animals turned into an R&B standard. No such establishment existed in Storyville, but history records that there was a Rising Sun Hotel on Conti Street in the French Quarter, a spot that burned down in 1822. It’s not much to go on, but when the building was purchased in 2005, archaeologists found the premises full of liquor bottles and makeup jars. Another theory holds that The Rising Sun was a person, Marianne LeSoleil Levant, who ran a brothel on St Louis Street. This was the spot that an unconvinced Eric Burdon was shown when he first visited New Orleans.

Gospel fervor

But if the brothels were partly responsible for nurturing New Orleans music, so was the church. Mahalia Jackson grew up singing at the Mount Moriah Baptist Church in the Carrollton district, and she called on that inspiration after moving to Chicago to launch her recording career. Her 1947 landmark, “Move Up A Little Higher,” introduced jazz improvisation to gospel; it sold an unheard-of eight million copies and got her to Carnegie Hall. The song also bore an implicit message of black empowerment, something she’d make clearer through a later friendship and collaboration with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. That was Mahalia Jackson shouting encouragement from the wings when he gave the “I Have a Dream” speech in The March On Washington.

The influence of the church would remain strong in local pop and R&B: for decades The Neville Brothers played “Amazing Grace” at the end of every show. And the church found its way into at least one rock classic. New Orleans native Merry Clayton has a story she’s fond of telling about falling asleep in church as a child, with her head on Mahalia Jackson’s lap. This was decades before The Rolling Stones booked her as a session singer for “Gimme Shelter,” finding themselves impressed enough to turn the last verse over to her. She was initially taken aback that anybody would ask her to sing about rape and murder.

New Orleans’ enduring soul queen, Irma Thomas has a strong church influence as well. Her one gospel album (1993’s Walk Around Heaven) is a joy, as are her annual visits to the Gospel Tent at the Jazz And Heritage Festival. You won’t hear these songs in her regular shows, since she believes that sacred and secular material should never be performed at the same time. But you can hear the gospel fervor in all her early hits, including “Time Is On My Side,” something that was less evident in the Stones’ better-known cover.

Also shaping New Orleans music was the marching ceremonies of the Mardi Gras Indians, a tradition (originally rooted in the kinship between escaped slaves and Native Americans) that is still enacted at carnival every year. Their tambourine-driven, call-and-response chants first made the pop charts in 1964, when The Dixie Cups cut a faithful version of the carnival standard “Iko Iko” (which later became an all-purpose party song, covered live by Grateful Dead, among others).

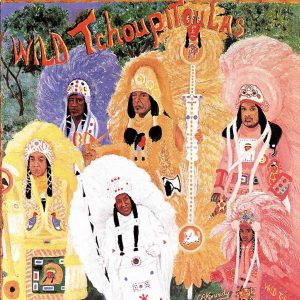

In the early 70s, two Indian tribes recorded seminal albums that combined the chants with a funk backdrop; first came The Wild Magnolias with arrangements by jazz/funk man Willie Tee (who’d hit the R&B charts a decade earlier with the salty “Teasin’ You”). More celebrated was the 1977 album by The Wild Tchoupitoulas, which featured The Meters as the main band and the first meeting of the Neville Brothers as a group.

Tell it like it is

Another hallowed spot, located just across Rampart Street from Congo Square, was J&M Studio, where owner Cosimo Matassa made records through the 50s and 60s. This was quite literally the birthplace of rock’n’roll – if you count Fats Domino’s 1949 classic “The Fat Man” as the first rock’n’roll record. It was certainly the point where Fats’ natural, easy-rolling charisma translated jump blues into something the kids nationwide could relate to. “Tutti Frutti” and Smiley Lewis’ “I Hear You Knocking” were also made there, and though the space is a laundrette now, you can still hear that legendary natural echo.

In 1955, Matassa moved his studio to Governor Nicholls Street across the French Quarter. This was where a young Allen Toussaint cut a jolly instrumental during one of his first recording sessions. It was early morning and the smell of fresh coffee from outside prompted Toussaint to call the song “Java,” later a Top 5 single for Al Hirt in March 1964.

Toussaint would be the looming presence in New Orleans music for the next two decades and then some. The songs he wrote and produced for a roll-call of artists including Irma Thomas, Jesse Hill, Ernie K-Doe, and Lee Dorsey, among others, sported a characteristic swing and elegance. Oddly, though, the first hit that he wrote and produced, “Over You,” for Aaron Neville in 1960, had a different mood entirely.

Toussaint pictured Neville as a proto-gangster character threatening revenge if his gal strayed. Neville (who later referred to “Over You” as “the OJ song”) wouldn’t make his national breakthrough until 1966, with the timeless “Tell It Like It Is,” one of the few original New Orleans R&B landmarks that Toussaint had nothing to do with. The house band for most of Toussaint’s sessions was, of course, The Meters, whose brand of slinky, supple funk became a trademark.

In the early 70s, Toussaint opened his Sea-Saint Studio at 3809 Clematis Street, in the Gentilly area. This was the spot where he produced “Lady Marmalade” by Labelle. By now it was such a quintessential New Orleans record that most people forget it was written by a New Yorker, Bob Crewe of Four Seasons fame. Sea-Saint is also where Paul McCartney dropped by in 1974, hoping to grab a bit of local musical color for his Venus And Mars album.

McCartney was such a fan of New Orleans music that he booked Professor Longhair and The Meters for a release party aboard the riverboat Queen Mary. Both of those sets have since come out on live CDs, and Professor Longhair’s performance is now getting a vinyl reissue as Live On The Queen Mary. Toussaint enjoyed relatively few hits in the 70s, though this was the era of his most timeless work, when his writing took on a stronger socio-philosophical slant. For evidence see “Hercules” (written for Aaron Neville, later covered by Paul Weller); “On Your Way Down” (written for Lee Dorsey and covered by Little Feat, among others) or the album The River In Reverse, his mutual-admiration session with Elvis Costello.

Right place, right time

New Orleans R&B took a profound left turn in 1968 when Mac Rebennack – a studio ace who was then paying his bills by arranging Sonny and Cher sessions – created his Dr. John persona on his first and most trailblazing album, Gris-Gris. The hippies felt right at home with the Doctor’s trippy imagery, but he was actually referencing something far more psychedelic: the city’s tradition of voodoo.

His world would intersect with Toussaint’s soon enough when they recorded the album In the Right Place At Sea-Saint, marking the only time the Doctor hit the singles charts. He’d go on to become one of the city’s great musical polymaths, cutting everything from lowdown funk to elegant standards albums in later years.

One landmark that’s still very much alive is Tipitina’s, named after a Professor Longhair song and formerly his longtime stomping ground. After some lean years, Longhair was rediscovered in 1971 when Quint Davis, producer of the fledgling Jazz And Heritage Festival, tracked him down at his janitorial job and persuaded him to play the fest. He wound up touring internationally and making major-label albums for the first time, winning a new young audience at home.

Go to the Mardi Gras

The city’s next generation of major players, including the five guys who’d form The Radiators, were in the audience if not in the pick-up bands. Though he left the world in 1980, “Fess” is still very much a presence at Tipitina’s. There’s a bust of him just past the front door, and legend says it’s good luck to give the Fess head a stroke. Nowadays Tipitina’s is the kind of funky, grassroots music club that every city needs, still emphasizing local music.

Though he wasn’t especially prolific, Longhair’s landmark recordings, “Tipitina,” “Bald Head” and “Go To The Mardi Gras,” remain essential texts for his inventive rhythms, his melodic imagination, and his beautifully absurd wordplay. New Orleans music’s next piano great was even more eclectic. James Booker was a legendary character whose genius could hardly be channeled. Just ask the producer of his Classified album, who sat with Booker for three rambling days only to get an album’s worth of sustained brilliance in the very last couple of hours.

On a good night, Booker was known to play classical pieces forward and backward, just because he could. On a bad night, he might never make it to the keyboard. Interestingly, Booker also had a short but notable career as a rock session man. If you want to hear worlds colliding, listen to his piano intersect with Marc Bolan’s guitar on Ringo Starr’s “Have You Seen My Baby.”

Like turning a radio dial

Notice that we haven’t mentioned Bourbon Street yet. Most locals and in-the-know visitors steer clear of that much-hyped area, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth a visit. The experience of a full-time, all-ages frat party is one that should be absorbed at least once. The music of Bourbon Street these days is largely karaoke and cover bands, and old covers die hard: after all these years you can still count on hearing a Bourbon band do “Sweet Home Alabama,” or a relatively new tune the likes of Santana’s “Smooth.”

It wasn’t always that way, though. During the 60s Bourbon Street was a whole lot seedier, and some timeless music grew from those seeds. Two of the city’s beloved instrumentalists, trumpeter Al Hirt and clarinetist Pete Fountain, had clubs on Bourbon and when they weren’t charming middle America on television, played into the night. The hippie freaks were in the mix too. During 1968-69, a motley Arkansas band called the Knowbody Else played nightly at the Gunga Den, a Bourbon club that was better known as the home of exotic dancer Linda Brigette (who was personally pardoned by the governor after being arrested for her “Dance Of A Lover’s Dream” routine). The band made one cult-classic album for Stax, including a song called “Vieux Carre,” about their wild life in the Quarter. They later moved back to their home of Black Oak, Arkansas, and changed their name accordingly.

At the time, strip clubs required live accompaniment instead of Prince CDs, and some of the city’s iconic rhythms, such as The Meters’ uniquely slinky hi-hat work on “Cissy Strut,” came out of those gigs. The glory days of New Orleans R&B were helped along by the availability of those gigs. “One of the cool things about New Orleans clubs in the 50s was that club owners booked the kind of music they personally liked,” Dr. John wrote in his memoir, Under A Hoodoo Moon. “If a guy liked Afro-Cuban, that’s what he booked. Another had a thing for blues, he went with that. Hog-wild about Dixieland, book the mother.”

Everybody has their pick for a current favorite spot, but there’s a good reason why music heads currently flock to Frenchmen Street. What’s often been described like turning a radio dial, the famed street is lined with clubs that regularly book jazz, blues, acoustic artists, solo pianists, gritty rock and roots bands, and local institutions such as the venerable Treme Brass Band. For the best results place yourself there on a busy night and let all the sounds wash over you. If it all starts to feel a bit overwhelming and otherworldly, you’re in the right place.

Planning a trip to New Orleans? Here are some must-see musical landmarks.

A guide to New Orleans musical landmarks

Congo Square

North Rampart Street

Now part of Louis Armstrong Park, this is the site where the first slaves are said to have laid down the African-derived rhythms that have permeated New Orleans music ever since.

J&M Recording Studio

838-840 North Rampart Street

The original site is one of rock’n’roll’s most hallowed spots: essential tracks such as “Tutti Frutti” and “I Hear You Knocking” were recorded here, before studio owner Cosimo Matassa moved his facilities to Governor Nicholls Street across the French Quarter. The original space is now a laundrette.

Cosimo Recording Studios

521 Governor Nicholls Street

After leaving North Rampart Street, Cosimo Matassa set up a new operation on Governor Nicholls Street. It was here that the legendary Allen Toussaint laid down the blueprint for the New Orleans sound of the 60s and 70s.

Sea-Saint Studio

3809 Clematis Street

In the 70s, Allen Toussaint set up his own recording studio here in the Gentilly area. The building is now home to a hairdresser’s.

Bourbon Street

Modern-day visitors are more likely to experience karaoke bars and round-the-clock frat parties, rather than traditional New Orleans music, but in the 60s Bourbon Street was the place to be, and it remains part of New Orleans’ rich history.

Frenchmen Street

Walking down Frenchmen has been described as like turning a radio dial, such is the variety of styles you’ll hear blasting out of the clubs. If you’ve come for the full New Orleans experience, this is the place to be.

New Orleans Jazz And Heritage Festival

Fair Grounds Race Course And Slots, 1751 Gentilly Boulevard

Founded in 1970, Jazz Fest is the second most important calendar event in New Orleans music, following Mardi Gras. With over ten stages offering a mouth-watering mix of music and local food, it’s not to be missed.

The best New Orleans music venues

dba

618 Frenchmen Street

Since opening in 2000, dba has become a reliable staple for jazz fans, and has also played host to a litany of legends, among them Eddie Bo, Clarence Gatemouth Brown, Dr John, Stevie Wonder and Afghan Whigs’ Greg Dulli.

Blue Nile

532 Frenchmen Street

With a dual reputation as a home for reggae and the longest-standing live venue on Frenchmen, Blue Nile claims to be “the original music club that gave birth to the music culture on Frenchmen Street.”

Tipitina’s

501 Napoleon Avenue

Named after a Professor Longhair song, and formerly the pianist’s stomping ground, Tipitina’s is still a buzzing hotspot for live music, supporting locals acts and grassroots events.

Maple Leaf

8316 Oak Street

Serving local music since 1974, Maple Leaf has inspired authors and poets alike, and continues to present the best of New Orleans’ wide-ranging local scene.

Republic NOLA

828 South Peters Street

Housed in a converted warehouse originally built in 1852, the Republic has everything – including three separate performance rooms and a state-of-the-art light system.

The Howlin’ Wolf

907 South Peters Street

Named after the legendary bluesman, The Howlin’ Wolf has a main hall and a smaller Den venue – plus a great mural painted in homage to New Orleans’ musical history.

One Eyed Jacks

615 Toulouse Street

Caters to all kinds of tastes, from jam bands to jazz-funk, and stages regular burlesque, comedy and throwback nights.

The Joy Theater

1200 Canal Street

Housed in a converted 40s cinema, The Joy boasts an art deco design and an eclectic programme offers a cross-section of music, cinema and culture.

The Fillmore NOLA

6 Canal Street

Modelled after San Francisco’s legendary Bill Graham-helmed venue, The Fillmore New Orleans suffered badly from Hurricane Katrina but reopened in February 2019, bigger and better than ever.

The Sugar Mill

Quite literally a 19th-century sugar mill, the design remains true to the building’s history, while the venue plays host to everything from corporate events to Mardi Gras balls.