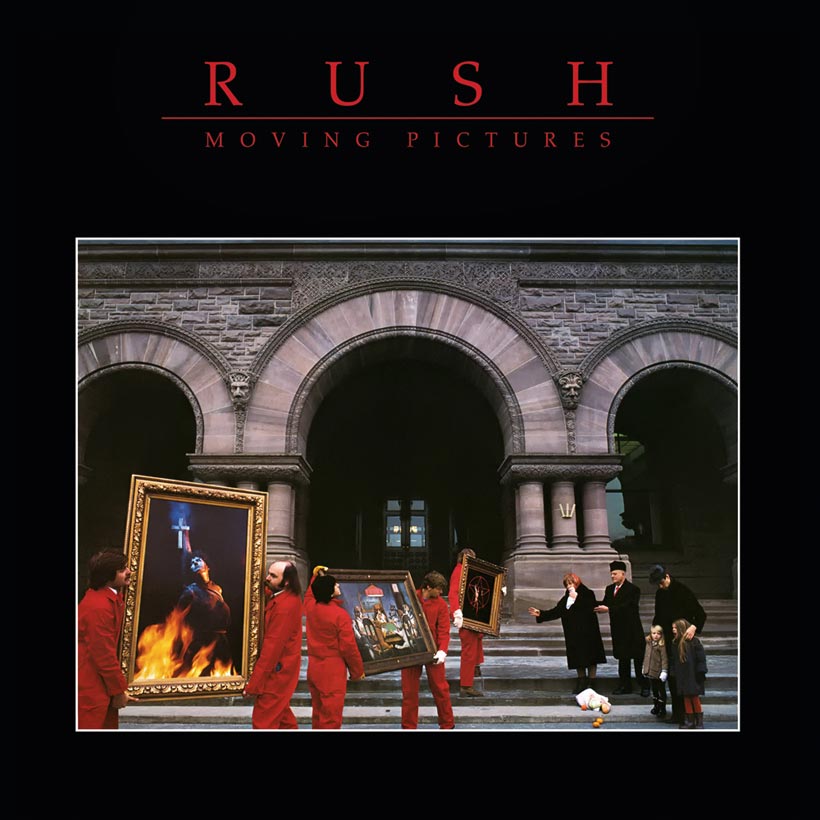

“Everybody got mixed feelings about the function and the form,” Rush declared in “Vital Signs,” the concluding track of 1981’s Moving Pictures. Fortuitously, however, it appeared that no one in the band’s burgeoning fan base had mixed feelings about Rush’s latest offering. (We’re playing with the context somewhat, but hear us out.)

Listen to Moving Pictures on Apple Music and Spotify.

As had always been the case where rock was concerned, function and form were of inarguable importance in 1981. If you’re predisposed to like certain kinds of music, and certain bands that exemplify certain kinds of music, it’s perfectly reasonable to seek signifiers so you can align yourself with your chosen tribe. Prog rock had represented a deeply engraved line in the sand – more of a fissure – even in its grandiloquent heyday, and it is generally accepted that punk ushered it smartly off the premises (though nothing is ever quite so cut-and-dried).

Certainly, by 1981, it didn’t seem at all unreasonable to conclude that the hirsute “dinosaur” rock bands who had tottered at inordinate length across prop-littered stages were laughably antithetical to the antsy, sharply-etched, pop-conscious combos who succeeded them. Concision was a key differentiator, whether this applied to song duration, hairstyle, or hem width. But it would be wrong to assume that all old prog hounds were grimly set in their ways by the tail end of the 70s, deaf to the alarms raised by the changing guard, heedlessly blundering towards an unlamented demise behind the Diminishing Returns store. Rush, for one, had been listening very carefully indeed.

A mid-point between past and present

As the steely focus of 1980’s Permanent Waves had already demonstrated, Rush had been genuinely enthused and rejuvenated by the infusion of fresh blood supplied by the nominal New Wave (The Police, XTC, Talking Heads), but it’s Moving Pictures that stands as their most graceful, perfectly weighted mid-point between a past that resembled a Roger Dean cloud map and a clean, straight-edged, digital present that fancied itself as Piet Mondrian thumbing a lift in a Tron cityscape.

If, in 1981, the skinny ties of the era looked slightly incongruous on Rush – bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee still sported a commendably abundant hairstyle – they nevertheless pulled off the small miracle of combining the snapping energy, urgency, and ruthless self-editing of “the new music” with the grandstanding, absurdly agile musicianship which represented their essential selves, swinging their double-neck axes in a stadium firestorm of thunderflashes and laser tracery. In doing so, they subtly broadened the horizons of doggedly polarised rock fans who considered pop/new wave/other to be frivolous, flimsy, and beneath contempt. Here was function, assuming a gratifyingly popular new form. (Following its release, on February 12, 1981, Moving Pictures went Top 3 in the UK and US, and all the way to No.1 in the band’s native Canada.)

“Tom Sawyer” exemplifies Moving Pictures’ modus operandi, with its gleaming, spacious, digital production, new-dawn synth, and a ringing, valorous chord sequence aimed at the far horizon. As with “Vital Signs,” it cleaves to drummer/lyricist Neil Peart’s oft-expressed, semi-autobiographical defense of the quietly adamant, often misperceived individual: “Though his mind is not for rent/Don’t put him down as arrogant.” (Ironically, all this talk of individuality translated as communality, striking a major chord with Rush’s enormous fanbase.)

A Rush cornerstone

“Red Barchetta,” meanwhile, is an open-road parable inspired by Richard Foster’s 1973 short story A Nice Morning Drive, and set in a future which now doesn’t seem too far away, in which the government heavily regulated how cars were built. It is clearly written from a government-regulators-gone-mad perspective (“A brilliant red Barchetta from a better, vanished time”), and the dichotomy it presents, pitting aesthetics and visceral thrills against health and safety, may be a discussion for another day. As an overall composition, however, it’s a Rush cornerstone, with guitarist Alex Lifeson supplying a pointillist constellation of glittering harmonics.

“YYZ,” named for the identification code of Toronto Pearson International Airport, is another Rush lynchpin: a jackhammer, bravura instrumental with a tritone interval straight from the King Crimson playbook. To these ears, it contains Lifeson’s finest recorded solo, an ecstatic, middle-Eastern ululation of dips and swoops.

Rush still couldn’t help themselves from laying down an old-school 11-minute set-piece-with-subsections, the densely effective “The Camera Eye,” dreamily pictographic in its vignettes (“An angular mass of New Yorkers… mist in the streets of Westminster”). Thereafter, the brooding and funereal “Witch Hunt” outgrows its Black Sabbath set-dressing to become a cautionary tale of regrettably eternal pertinence: “Quick to judge/Quick to anger/Slow to understand/Ignorance and prejudice/And fear walk hand in hand.”

Best of all, “Limelight” rides in on such an appealing, immediate, and compact riff that it can only be classed as pop music… albeit pop music with a characteristically insular lyrical agenda (“One must put up barriers to keep oneself intact… I can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend”), and, as it’s Rush, bars of 7/8. In many ways, it’s a song that defines them: decent, diffident men, permanently enshrined in memory on the world’s stages but bemused by the devil’s bargain that this always entailed.