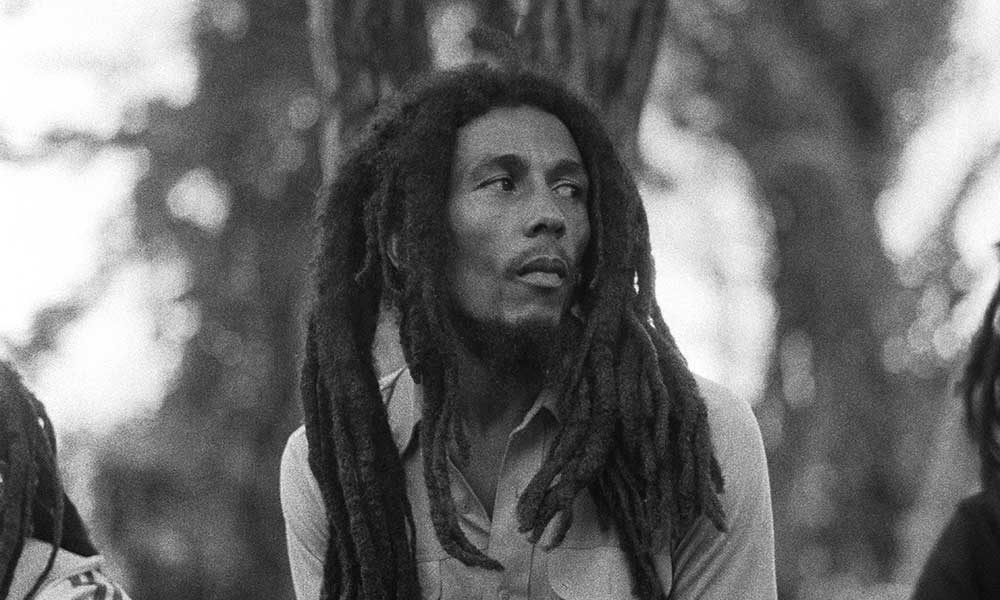

Like the vast majority of the Jamaican population in the 50s and 60s, Bob Marley was brought up a Christian. He sang church songs, made gospel records with The Wailers, and praising a Christian God was always within his thoughts. Given these facts, it might seem strange that the same young man became the first and foremost figurehead for another faith – and found that the wider world was willing to listen when so many in his Jamaican homeland rejected his adopted religion and considered its adherents to be outsiders. Through songs such as “Exodus,” “Rastaman Chant,” and “War,” Bob Marley did so much to deliver the message of Rastafarianism to the globe, but it was not all one-way traffic. In return, Rastafarianism did much to deliver Bob Marley’s music to the world.

Finding Rastafarianism

Bob always had a message to impart. His very first single, “Judge Not,” recorded in 1962, warned a critical person not to examine his actions but instead to ready themselves for the judgment day we must all face. His early records with his original vocal group, The Wailers, likewise had plenty to say for those who would listen. “Simmer Down” (1964) talked down a hothead; “Rude Boy” and “Good Good Rudie” took contrasting and increasingly aware positions on the 60s Jamaican hooligan phenomenon. There were gospel outings, too, such as “Straight And Narrow Way” and “Let The Lord Be Seen In You.” However, in 1966, Bob’s spiritual path took a sharp turn when Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia visited Jamaica.

Jamaica’s Rastafarian community worshipped the Ethiopian leader as a living God, the savior who would one day appear in Africa as a liberator of the black consciousness. Indeed, their very name was taken from “Ras,” meaning Lord, and “Tafari,” Selassie’s family surname. Emperor Selassie’s presence as a black African ruler from the Rastafarian homeland of Ethiopia was taken as a second coming for Rastas. Now he was to land on the island where many held this belief. His Imperial Majesty was met off the plane in Kingston by Mortimer Planno, the Rastafarian teacher and philosopher who was one of the key figures in the faith, and who was able to calm the devotees – 100,000 of them by some estimates – who had come to greet the Emperor.

Such a huge turnout was a manifestation of the allure of Rastafarianism. The faith’s rejection of what it saw as the remnants of slave society and its values, its adherents’ decision to “throw away the comb,” their devotion to ganja-fuelled meditation, and the hypnotic heavy hand-drumming that accompanied it, fascinated many Jamaicans. Rastafarians’ ability to quote from the Old Testament as if its events happened yesterday gave the religion a recognizable message and an immediacy for those raised as Christians. But mainstream Jamaica rejected the Rastas, seeing them as long-haired, unwashed drug-taking outlaws and idlers. The faith was an alternative consciousness on the island, readily identifiable in person on the streets of Kingston and Spanish Town, and high in the hills and beaches out of town, where lengthy sessions of music, chanting and mindfulness could be found for those so inclined.

From time to time, mainstream society would be forced to take notice of Rastafarianism, as when The Folks Brothers’ “Carolina” became a huge Jamaican hit, built on the burru drumming of Count Ossie; or in 1966, when Kingston was suddenly full of dreadlocks, all here to see their King and Lord. Present on the crowded streets just outside the airport was Bob’s wife, Rita. Bob was away working in Delaware, in the US, and like many young Jamaicans he’d developed a fascination for the ways of Rastafarianism, though he had not yet entirely embraced it. Bob wrote to Rita when he heard about the Emperor’s visit, and suggested she go to see for herself. Rita found herself looking for signs, proof that this small, smartly-dressed figurehead was indeed deserving of holy status. She believed she saw it as he passed: she noticed his palms were marked, as if they had the stigmata.

Free to express Rasta beliefs

By the time Bob had returned from the US, Rita was entirely converted to Rastafari, and her unshakeable belief was the tipping point for Bob’s destiny: a conversion to the faith. He took instruction in the religion from the learned Mortimer Planno and, funded by his trip to the US, The Wailers opened their own record label, Wail ’N Soul ’M, through which they felt free to express Rasta beliefs. His partners in the group, Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh, were also devoted to the Rasta way; Tosh cut the fierce “Rasta Shook Them Up” at the Studio One label after HIM Selassie’s visit; Bunny Wailer delivered Rasta-influenced tunes such as “I Stand Predominate,” which used the term “I and I”, one of the first times the Rasta expression of unity with God was heard on record. Together at their new label, the group created singles such as “Bus Dem Shut (Pyaka),” “Selassie Is The Chapel,” and “Freedom Time,” the latter of which made direct reference to slavery; some of its lyrics were reworked for “Crazy Baldhead” on 1976’s Rastaman Vibration.

However, Wail ’N Soul ’M was not a conspicuous success. Despite the excellence of their releases, it seemed Jamaica was not entirely ready for The Wailers’ Rasta rocksteady, preferring this silky music to be accompanied by lyrics of love. Bob and the group began scouting for a sympathetic producer and label who understood their message. After several unsatisfactory professional pacts, they spent a year or two under the guidance of Lee Perry, which proved far more to Bob’s liking. Over the course of two albums, The Wailers laid foundations for their future success.

Bob in particular benefited from the liaison, writing several songs he’d return to during his time as a superstar, while honing his vocal style, leaving behind the traces of the US soul stars he’d admired as a youth. Songs such as “Corner Stone” and “Small Axe” were heavily inspired by Rastafarian philosophy, telling of how the folk that society despised must rise, and “Kaya” was celebration of marijuana as pleasure, support, and spiritual necessity. Peter Tosh’s “400 Years” was an acidic observation of how slavery still had a marked impact on black people. But by the end of 1971, The Wailers were focused on their second self-owned label, Tuff Gong, again seeking artistic freedom and financial independence.

The Wailers’ songs, such as “Redder Than Red” and “Satisfy My Soul Jah Jah,” covered Rasta themes, but even when they signed to Island Records and began to build a profile that would eventually see Bob becoming one of the biggest musical icons of all time, there was never any sense that The Wailers would forget their mission from Jah (God). “Concrete Jungle” contained the haunting couplet “No chains around my feet but I’m not free/I know I am bound here in captivity,” echoing the Rastafarian belief that they were still held in a slave society. “Midnight Ravers” drew parallels between the breakdown of morals in 70s nightlife and an apocalypse foretold in the Book Of Revelations; their first Island album – of two they released in 1973 – was even called Catch A Fire, meaning: burn in hell. Compromise? No way.

A call for unity

And so it went on. “Hallelujah Time,” from Burnin’, referred to slavery; the same album’s “Rastaman Chant” delivered the folksy, heavenly sound of raw Rastafarian music to the wider world’s ears. Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer left the group, but Bob’s progress continued with the support of his vocal foils The I-Threes. Natty Dread (1974) took a derisive term sometimes used about Rastas in Jamaica and turned it into a badge of honor, the title track portraying a network of believers who could not be mocked but who knew who they were: the very soul of their society, even as that society rejected them. This was an earlier theme reiterated: 1970’s “Corner Stone” had a similar message. Even better, the moving “So Jah Seh” steadily offered a story of hope and redemption: if you were right, and as a dread you surely were, you were not born to suffer, you were to be protected. It was a triumph without being triumphalist.

Rastaman Vibration (1976) went even further, with the stirring and powerful “War” paying tribute to, and disseminating far more widely, the speech HIM Haile Selassie gave to the United Nations in 1963 about why inequality and oppression will always lead to conflict. “Crazy Baldheads” mocked straight society, pointing out that the one paid to build the jail is the one most likely to wind up in it; the baldheads are the police, the politicians, the slave owners, the non-dreads. Before this, Bob had paid almost immediate tribute to the Emperor Haile Selassie, who had died on August 27, 1975; Rastafarians do not believe in death, considering life an eternal state for the righteous, and Bob’s moving “Jah Live,” cut within days of His Imperial Majesty’s passing, emphasized that the lack of an incarnate presence of the Rastafarian God did not mean that he was no longer able to guide and protect the lives of believers.

Bob turned adversity into victory with 1977’s remarkable Exodus, recorded in London, where Marley had relocated after an attempt on his life in Jamaica. This transatlantic shift gave him pause to reflect on the life he’d temporarily left behind, resulting in the title track becoming an anthem for the “movement of Jah people,” who sought a return to mother Africa. There was also “Guiltiness,” which suggested that the consciences of the oppressors could never rest, and “The Heathen,” which declared that Jah must inevitably win, no matter how hot the battle might be. Plus there was a revival of The Wailers’ mid-60s classic “One Love”/”People Get Ready,” a call for unity in the sight of Jah.

A fight for freedom

Bob knew that the fight for freedom must be fought on many fronts. “Babylon System,” from Survival (1978), cast the rich and the bosses as vampires, sucking the blood of the sufferers; it chides those who teach the lies of history, and also mentions wine, a reference both to slavery and the sacrament, a Christian ritual that Rastafarians would have no part of. The same album’s “Wake Up And Live” called on people to discover themselves and their life’s meaning before they died. “Zion Train,” from Uprising (1980), took a familiar gospel metaphor and adapted it to the Rastafarian quest; “Forever Loving Jah” made it clear that Bob’s path would not suffer a diversion. The beautiful “Redemption Song” found Bob leaving one last testament to his faith for us all to absorb: he may have been the son of slaves, but there were bigger powers in life than those of man’s making, and he walked without fear as he approached his passing from cancer in May 1981. What did he have to fear, since death was just a fraud when you were a believer?

The posthumously released Confrontation (1983) was packed with meaningful songs such as “Buffalo Soldier,” “Blackman Redemption,” and “Jump Nyabinghi,” all paying testament to Bob’s faith in Rastafari. Along with his undying status as the crucial propagator of music with a message, it made it clear his mission as Rastafarianism’s great representative in the wider world would never stop. Generations have since absorbed and adored Marley’s message. His work, Jah’s works, continue. Jah live, indeed.

Listen to the best Bob Marley songs on Apple Music and Spotify.