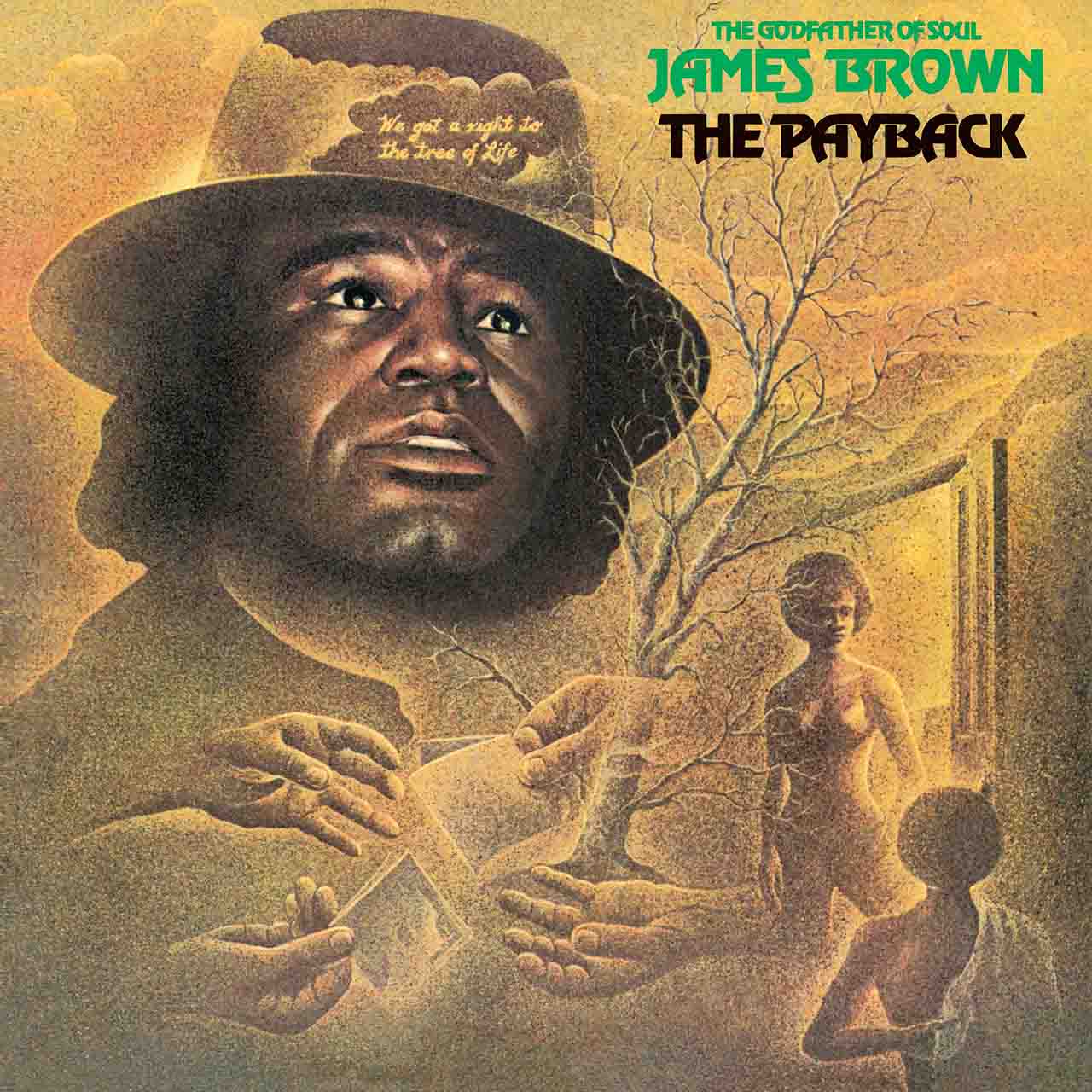

For many fans, “The Payback” is James Brown’s greatest song. For others, it’s his funkiest. Let’s think about that some: James Brown spent the best part of half a century recording, releasing records non-stop in the 60s and early 70s. He was the founding muthafather – maybe the inventor – of funk. To simply be in contention for the twin crowns of his best record and his funkiest means “The Payback” is one helluva tune.

Revenge is his right

From the slow-rollin’, steady-mobbin’ opening bars, clearly on a mission, you know “The Payback” is going to be all killer, no filler. That groove, dark, deep and unfussy, thumping in your ears like a stressed heartbeat, ONE-two-three-four; the stratospheric vocal from Martha High like a siren warning of trouble; Fred Wesley’s horn section blowing like distant car horns blocks away; that chattering wah-wah like the awed gossip of bystanders on the corner, watching the gang going to fix a problem once and for all; the bassline, pensive and clearly unresolved. Over the top, Brown growling – not hysterical, but stating that revenge is his right and your unwanted destiny.

And that’s just the intro.

A keystone of funk music

First released in December 1973 on the album of the same name, “The Payback” is one of the keystones of funk. The music was well established by now, having practically been driven into public consciousness by Brown from 1967, though he was building the sound from 1962 onwards.

There was probably an element of Brown being regarded as old school by 1973, when he was recording the soundtrack for a Black action movie, Hell Up In Harlem. But hey, who was more badass, more funky than Mr. James Brown? If anybody was built to deliver the soundtrack for a “blaxploitation” picture, it was surely him; didn’t they call him The Godfather? Yet Isaac Hayes (Shaft), Marvin Gaye (Trouble Man), and even Bobby Womack (Across 110th Street) had claimed the accolades.

“The same old James Brown stuff” – perfected

Brown’s two soundtracks thus far, Black Caesar (1972) and Slaughter’s Big Rip Off (1973), had been decent, surprisingly subtle efforts, and their corresponding albums are now much sought by funk fiends. But given a third opportunity, Brown was going to make sure he delivered a monster, and he surely had first dibs on the sequel to Black Caesar, Hell Up In Harlem. He’d show them who was the lion in this particular amphitheater. It was going to be the funkiest soundtrack of all time.

Except it didn’t work out that way. Brown spent much of his studio time in 1973 holed up with his musical director, Fred Wesley, concocting a set of tunes built to be the perfect stylistic match for this screenplay about Harlem’s top criminal operator. He confidently delivered them to the movie’s producers – who rejected it, calling it “the same old James Brown stuff.” And they were right: this raw-to-the-core, boiled-to-the-bone sound was the same old James Brown stuff – perfected. The singer even claimed that Larry Cohen, the movie’s director, told him it “wasn’t funky enough”, though that claim was vehemently denied. Edwin Starr landed the soundtrack commission instead.

Soul-soaked menace

But JB never took a damn thing lying down. He finished his tracks and assembled a double-album, The Payback, now regarded as one of the classics of 70s African-American music. And the lyrics of the single, cropped from a groaning, growling seven-minutes-plus on the album, speak of vengeance, violence, and being pushed beyond his tolerance. Brown served this dish cold, releasing it in February 1974 – the second single from the album. It was too uncompromising, too intimidating, to climb beyond the Top 30 in the US pop charts, but it went gold, hitting No.1 in the R&B chart, where its edgy drive was welcome. It was one of three occasions that James Brown topped the chart in that year. If he was past his prime, nobody told Black America: “The Payback” was a smash with the audience Hell Up In Harlem was aimed at.

Brown’s lyric may have been menacing, but it was not without humor, and certainly down with his times. Amid a list of things he could and could not dig, such as dealing, squealing, scrapping, and backstabbing, he drops the line, “I don’t know karate, but I know ker-razor.” Brown had noted that America was in the grip of martial arts fever back then, and Black audiences dug Bruce Lee as much as they dug Richard Roundtree or Pam Grier. In its single mix, “The Payback” had an unusual atmosphere-raising addition: DJ Hank Spann, known as The Soul Server, delivered interjections such as “This is for Chicago!” “This is for Atlanta!” and “This record is too much!” like he was talking over the record as it spun on his decks at WWRL in New York City. It seemed to make the single all the more soul-soaked and blessedly Black.

The Payback’s legacy

“The Payback” had an influential afterlife. Brown “versioned” it for “Same Beat,” credited to Fred Wesley And The JB’s, laying a different melody over John “Jabo” Starks’ drum pattern from “The Payback” and releasing it as a single a month ahead of that track. Hank Spann again provides interjections – and there were samples from Dr. Martin Luther King in a time before samplers existed. Brown’s apparently genuine ire at David Bowie and John Lennon’s “Fame,” which he believed borrowed the lowdown groove from “The Payback,” caused him to create “Hot (I Need To Be Loved Loved Loved),” a tune that cloned “Fame” down to the fuzzbox guitar riff. In 1980, Brown, having noticed a new trend in youth music, cut “Rapp Payback (Where Iz Moses?),” using the 60s soul man’s spelling of “rap.” Brown had always liked to rapp on his records, why not make a tune with a touch of his old vibe matched with horns designed to work like they’d been cut on a Sugar Hill record? However, his message for the hip-hop generation remains unclear, as this song features perhaps the least-comprehensible of all Brown’s vocals.

By the time hip-hop was in full swing in the mid-80s, “The Payback” was fair game for re-use and interpolation. Ice Cube sampled it twice, including on the self-explanatory “Jackin’ For Beats.” EPMD bit off a chunk at least four times, with “The Big Payback” acknowledging the source in its title, and Redman was another regular subscriber. “The Payback” fed two of the biggest R&B hits of the early 90s in En Vogue’s “Hold On” and “My Lovin’ (You’re Never Gonna Get It).” More recently, it informed some of the lyrics and much of the attitude of Kendrick Lamar’s “King Kunta.”

The attitude was a major legacy of “The Payback,” and some have cited it as the spark for gangsta rap. More than this, it’s so raw, so spare; The Godfather treated the backing track like a breakbeat: a beat and a rhyme, a beat and a raw vocal, declaring that the man was dealing with a problem, and this shit is going to end – in the big payback.

Listen to the best of James Brown on Apple Music and Spotify.