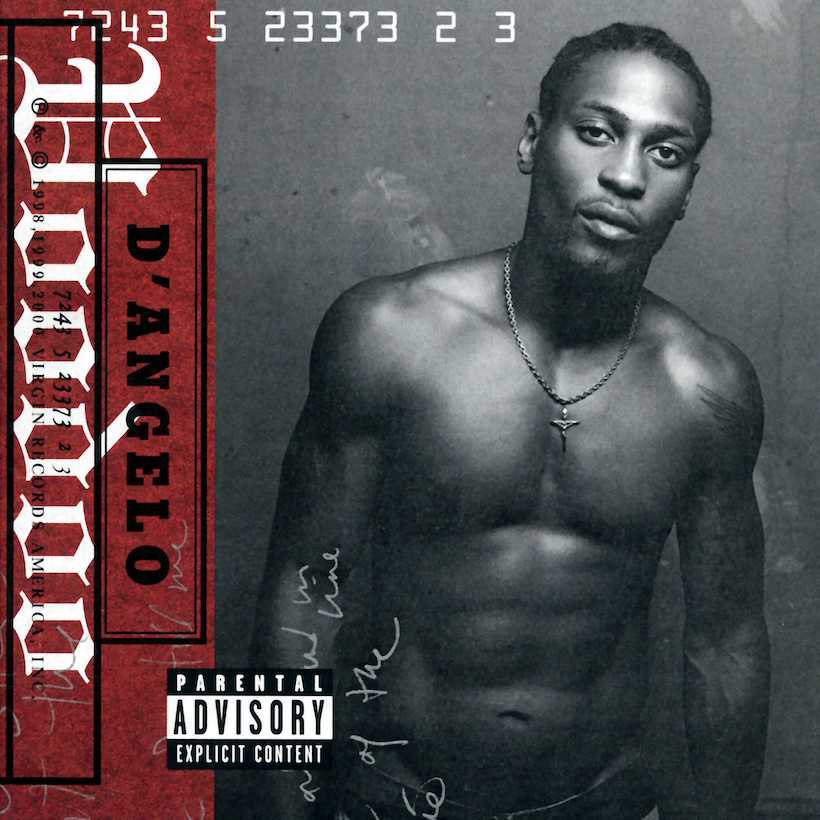

D’Angelo’s neo-soul masterpiece is remembered not only for the indelible mark it left on R&B but also the impossible story behind bringing the album into existence. Released on January 25, 2000, just one month into the new millennium, Voodoo would define the decade, setting the bar so high with its ingenuity and progressiveness that wouldn’t be met until D’Angelo returned 14 years later with Black Messiah.

Considered “post-modern” and “radical” at the time, Voodoo can’t lay claim to any one era. Produced in the 90s, and assembling sounds and ideas from 60s, 70s, and 80s funk and soul, it represented a coalescence of every great black innovator of the past – Jimi Hendrix, Curtis Mayfield, George Clinton, Sly Stone, Stevie Wonder, Al Green, and Prince – and produced something that was built to last.

Once hailed as the next Marvin Gaye, D’Angelo become the harbinger of hip-hop soul with his first release Brown Sugar in 1995. At the ripe young age of 21, he was responsible for rethinking an entire genre and had laid the path for Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite (’96), Erykah Badu’s Baduizm (’97), The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (’98), and the neo-soul movement. But on the dawn of Y2K, contemporary R&B had morphed into a slick, club-friendly state. Voodoo emerged as a response to this, bringing back earthy 70s production powered by experimental, hip-hop-influenced rhythms.

After its release, Voodoo topped the Billboard albums chart just two weeks later, won two Grammy’s, achieved platinum status, and produced a hit that would turn D’Angelo into a pin-up for ages. The album made an arresting statement, not just musically but visually. With its cover and provocative video for “Untitled (How Does it Feel),” D’Angelo bared more than his soul. What perhaps meant to be a vulnerable statement looked more like an illicit invitation.

D’Angelo’s perfectionism is well documented and with the fate of R&B foisted upon his shoulders, he was debilitated by the fear of the sophomore slump and determined not to make another Brown Sugar. During the five year interim between the two records, he’d switched managers, changed record labels, made brief cameos, and tinkered in the studio for years on end. Fans held out hope, with two promo singles, first the sample-driven “Devil’s Pie” in ’98 and “Left and Right” with features by Redman and Method Man a year later.

When it came time to record, D’Angelo took a page from his predecessors and set out to create a spontaneous, jazz-like approach to recording. Recruit the best R&B musicians around, give them free rein to jam, and capture the magic on tape. A method that harkened back to how funk records were made in the pre-Napster era. As D’Angelo told Ebony Magazine at the time, he wanted to “make strong, artistic Black music.”

As if trying to conjure up the ghost of Jimi Hendrix and all those that recorded there, D’Angelo decamped to Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village and brought his motley crew of fellow musicians to soak in soul and rock records and try to recreate some of the magic that had been made there. These studio sessions went on for years, but the result was an organic, in-studio sound that can only be pulled off by masters of their craft. The real players behind the curtain were Questlove (The Roots) on drums, Pino Palladino on bass (John Mayer Trio, The RH Factor), guitar veterans, Spanky Alford and Mike Campbell, fellow Roots member James Poyser on keys, and jazz prodigy Roy Hargrove on horns.

D’Angelo’s soul revivalist vision didn’t stop at just the studio setting. He didn’t want it to just feel like old soul, but to sound like it as well. It’s a shame his analogue obsession pre-dated the great vinyl renaissance, but we all get to reap the rewards now. Employing vintage gear and recording instrumental takes live, it seemed wasted on the mp3 era.

For an R&B album, Voodoo eschews common song structures and instead feels like an on-going conversation – a peek inside D’Angelo’s stream of consciousness. While its freeform, downtempo aesthetic alienates some, its intoxicating and jazz-like vibe surprises with each listen. With each track clocking in at six minutes or more, it wasn’t exactly radio-friendly. And its heavy use of back phrasing further puts you into a state of drugged euphoria. The album’s title takes on a literal meaning, it’s full of speaking in tongues, divine healing, and mystery.

The spoken word intros, outros, and bits of dialogue were a commonly used device at the time, (see any rap album and other neo-soulites (Lauryn Hill) that have only recently made a comeback on Solange’s A Seat At the Table. Amid these layered vocals, there is a heavy emphasis on guitars and horns on “Playa Playa” and especially “Chicken Grease” that puts the funk front and center. “The Line” meanwhile features more confessional lyrics, as he answers his critics “I’ve been gone, gone so long. Just wanna sing, sing my song, I know you’ve been hearin’, hearin’ a lot of things about me” in his breathy falsetto.

Sampling takes on an important role throughout the album, a practice that had been honed over the past decade, but D’Angelo does so with care, whether it’s Kool & the Gang‘s “Sea of Tranquility” on “Send it On” or the drums from Prince’s “I Wonder U” on “Africa.” Every track serves a purpose, there is no filler here. His cover of Roberta Flack’s “Feel Like Makin’ Love” is turned into a breezy song of seduction, while the Latin jazz-infused “Spanish Joint” hints at the heat to come.

But none of these songs fully prepare you for the ultimate slow-burn ballad that is “Untitled (How Does it Feel).” Co-written by Raphael Saadiq, it shall go down in the annals of makeout music history and even cuts off in the middle, leaving you wanting more. Whether consciously or subconsciously inspired by the “Purple One,” it was ironic that Prince seemed to be inspired as well, releasing “Call My Name” just a few years later.

Given such a beguiling track, it needed an equally provocative video to accompany it. At a time when every R&B video was dripping in bling, D’Angelo’s Grecian torso actually felt stripped down rather than an erotic performance. The song was a blessing and a curse. The video turned him into a sex symbol overnight but it also led to him becoming a recluse over the years. Voodoo still stands as a wildly innovative, forward-thinking, and challenging record, who knew it would take 14 years for D’Angelo to top it? As Questlove put it: “How can I scream someone’s genius if they hardly have any work to show for it? Then again, the last work he did was so powerful that it’s lasted ten years.”