In early 1972, Linda Ronstadt was the archetypal promising-but-underperforming artist who just couldn’t get a breakout hit. She already had five albums on her CV – three with country-rockers The Stone Poneys, two solo – but only once had she connected with the public in a big way: on the Poneys’ chiming single “Different Drum,” which made her briefly ubiquitous in 1967. Hearing her sing it, said Jackson Browne in 2019, was like “pull[ing] back the covering of a fully developed vocal stylist.”

There’d been a flurry of excitement around a 1970 ballad, “Long, Long Time,” resulting in a Grammy nomination, but it had come to nothing. And so there she was in January 1972, seeking a launchpad. There was also pressure from Capitol Records, which had invested in her career, setting her up with different producers and with some of the era’s best new songwriters. Her failure to properly take off seemed inexplicable: she had the pipes, she had the ability to put her own aching stamp on other people’s tunes (not a songwriter herself, she mainly used other artists’ material). She certainly had the marketable looks. What was the issue?

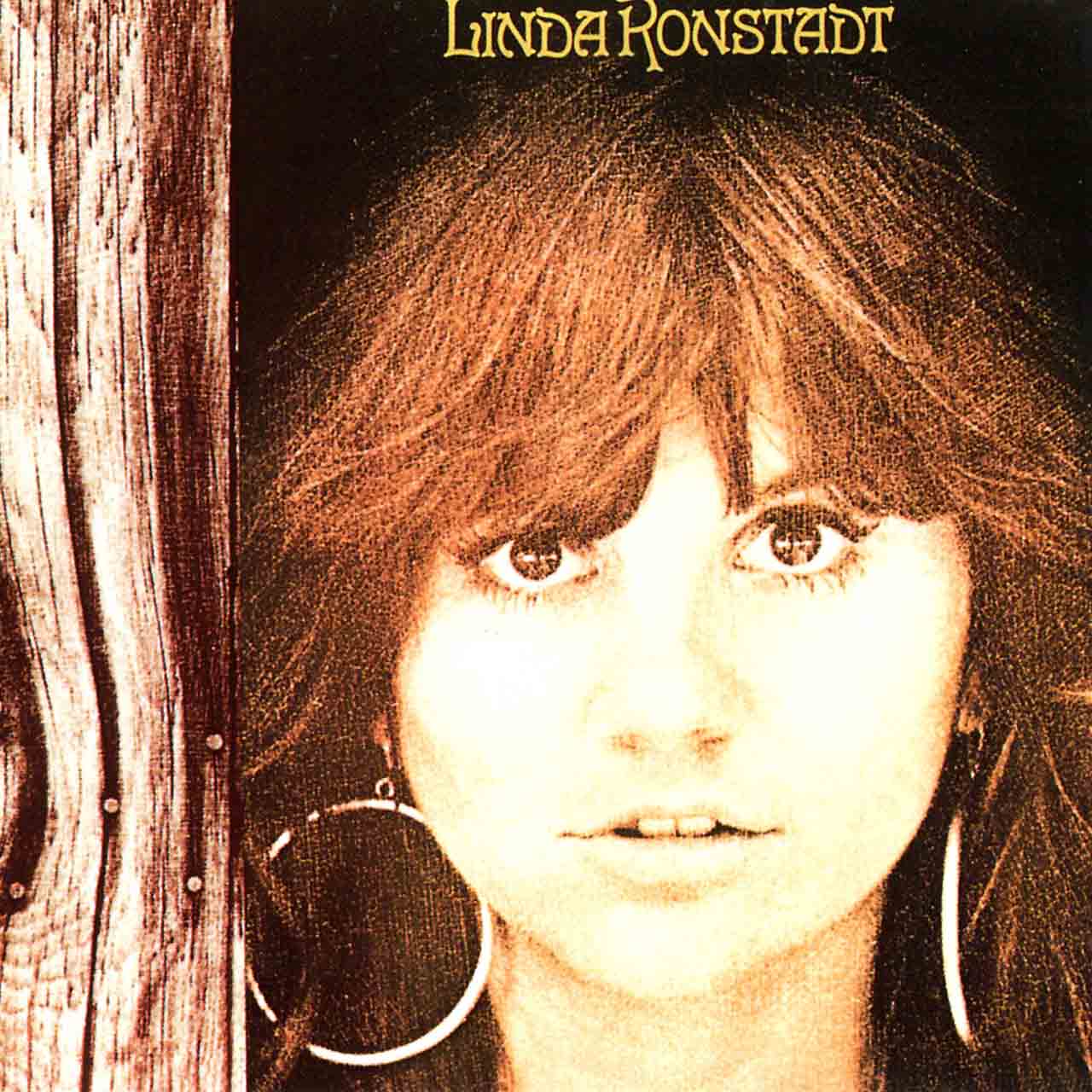

Maybe it was just the stars finally aligning, but in the third week of January, the launchpad materialized. Linda Ronstadt didn’t make a huge commercial splash – it reached 35 on the country chart, 163 on the rock – and produced no major singles, but it was the record that primed the 25-year-old singer for superstardom to come. And superstardom was the only word for it: from the mid-‘70s to the early 80s, she was the most successful female vocalist in rock, with a CV packed with groundbreaking achievements, from being the first woman to have six consecutive platinum albums to be the first to sell out arenas in her own right.

Listen to Linda Rondstadt’s self-titled album now.

How did Linda Ronstadt rev up her career? In a word: subtly. Though it was a crossover record, there was no boundary-leaping new direction; its power was in its deft introduction of rock to her country sound, just as country music – the California-hippie sort she’d specialized in – was starting to sound tired. She and producer John Boylan used new songs by young rock writers like Neil Young, Jackson Browne, and Eric Kaz. They assembled a studio band who’d already toured with her and knew where she was headed on this new album (the band later named themselves The Eagles, and did pretty well). And Ronstadt, muscular and heartfelt, gave some of the performances of her life.

Listen to Young’s “Birds,” a close-harmony tour de force in which she leads the band through the song’s delicate peaks and troughs. It’s so shimmeringly perfect it’s hard to believe it was recorded at a gig (the Troubadour in Hollywood, in early 1971). Then hop to “Rock Me On The Water,” and hear her interpretive ability on Browne’s farewell-to-the-‘60s ballad. “While your walls are burning and your towers are turning/I’m going to leave you here,” she sings, sorrowful but resolute. Her tone is as fragile as glass. This album is where the depth and maturity she was nurturing on her first two albums, Hand Sown…Home Grown and Silk Purse, really blooms.

Ronstadt didn’t abandon country, as illustrated by versions of Patsy Cline’s “I Fall To Pieces” and Johnny Cash’s “I Still Miss Someone.” But they’re delivered without the twang that marked Silk Purse, which was recorded in Nashville, Across the album, you can hear her gently pulling away from her roots: the next two albums, Don’t Cry Now and Heart Like A Wheel would make more decisive inroads into the soft-rock style that would define her. Heart Like A Wheel was the one that made her a household name, and Linda Ronstadt is best heard as a fascinating transitional record – the one before the one before the one.