Chess Records is synonymous with the Chicago electric blues scene of the 50s, when iconic names such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, and Chuck Berry came to prominence, helping to establish Leonard and Phil Chess’ Windy City indie label as one of America’s leading proponents of R&B music. But it’s often forgotten that a jazz pianist called Ahmad Jamal played a major role in filling up the label’s coffers and widening its audience.

At 89, Jamal is one of the last giants from jazz’s golden age of the 50s who’s still active musically. Though he’s semi-retired, the veteran pianist still pops up now and then for one-off concerts and continues to record on a fairly regular basis (his 67th album, Ballades, a collection of solo and duo pieces, was released in September 2019).

Talking to uDiscover Music from his home in New England, Jamal casts his mind back many decades to reminisce about a special event he performed at. “It was a historic concert in Carnegie Hall that entrepreneur Morris Levy presented for Duke Ellington’s 25th anniversary,” he explains. “On the bill was Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz… and me.” Jamal still has the poster from that 1952 concert – “They spelt my name wrong, A-M-A-D,” he laughs – which he treasures, saying he’s looking at it as he speaks.

“It was my first appearance at Carnegie Hall but I’m the only one of the headliners still living.” He says this with a tinge of wistfulness, adding, “So now, at 89 pushing 90, I value every moment because none of us are getting out of here alive.”

How Ahmad Jamal Got To Chess

He follows this statement with a long, self-deprecating chuckle. But despite his apparent abundance of mirth, Jamal is a seriously talented musician. He’s originally from Pittsburgh: a child prodigy who started playing piano at three and, as a teen, caught the ear of jazz great Art Tatum. Then, after moving to Chicago, in 1948, he was eventually discovered by visionary record producer John Hammond, the patrician entrepreneur who had brought Billie Holiday to prominence and later helped to bring Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan to the attention of the wider world. Hammond gave Jamal his first shot at recording in 1951, but it was seven years later, when the pianist was signed to Chess Records, that his career truly skyrocketed.

Recalling how he joined Chess in 1956, Jamal says, “I recorded short-term for a small company called Parrot, owned by a DJ and radio personality called Al Benson. He was attracted to my style, so I made some recordings for him and he then sold those masters to Leonard Chess. So that’s how I got with them.”

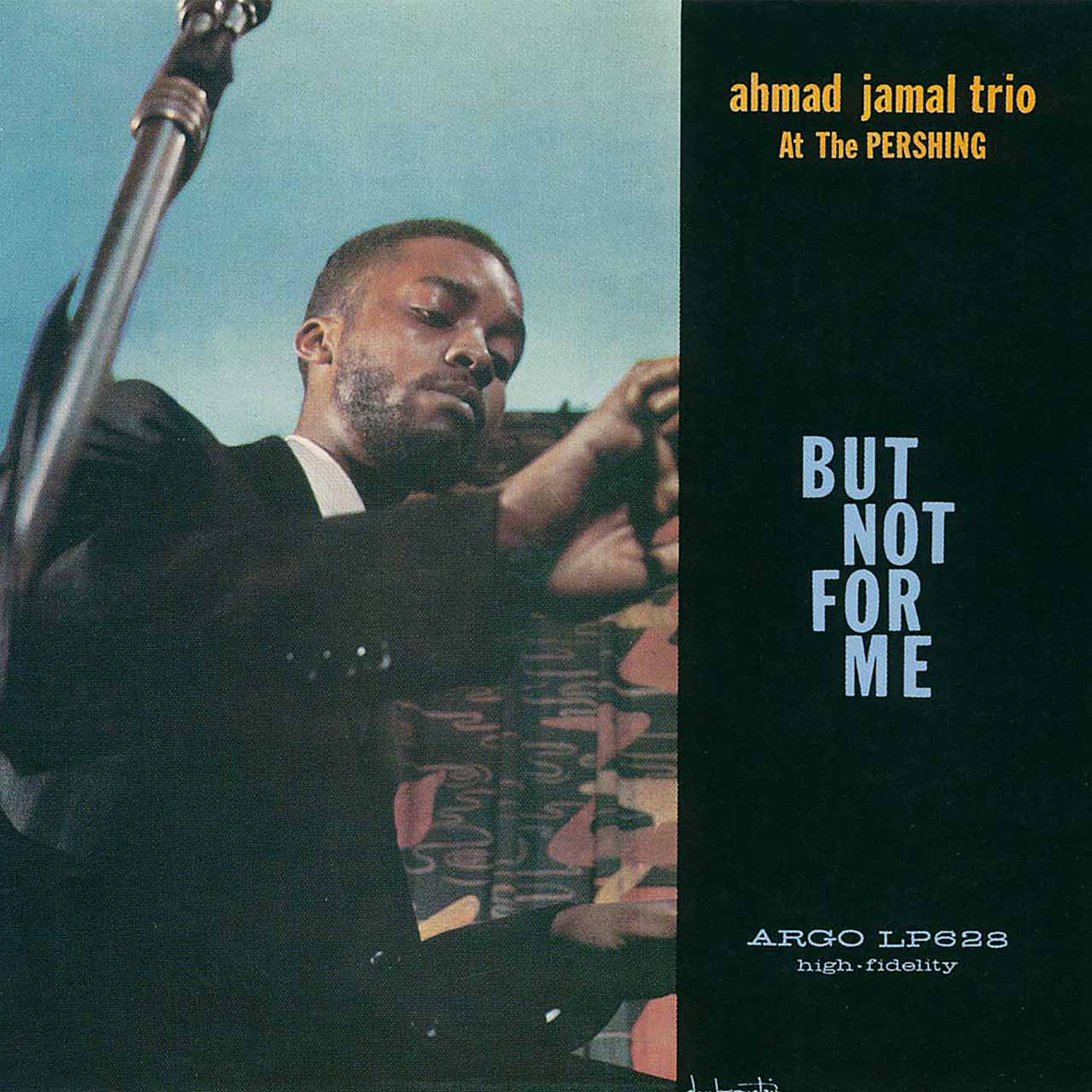

But it was two years later when Jamal hit the jackpot, and it was down to one definitive record: At The Pershing: But Not For Me, recorded for Chess’ jazz imprint, Argo. It captured Jamal’s then trio (with Israel Crosby on bass and Vernell Fournier on drums) during their residence at The Pershing Hotel in Chicago during January 1958.

The reaction to At The Pershing

At The Pershing: But Not For Me was much more than a record: it was a phenomenon. Its fame and popularity spread like wildfire. It topped America’s jazz charts for months and established a 107-week residence in Billboard’s album charts.

“That album sold over one million copies and is still selling.” There is a palpable sense of incredulity in Jamal’s voice, as if he still can’t comprehend the record’s success and astounding longevity. Musing on why it resonated with so many people, the pianist attributes it to the power of music: “It’s contagious. Music belongs to the world. So something that is of value, whether it’s Ravel’s Boléro or, specifically, At The Pershing, the world listens. And if it’s good, you’re going to get one or two listeners… and I got a few more than two!”

The record certainly changed Jamal’s life, transforming the then 28-year-old into a household name. “I could write volumes about that,” laughs Jamal. “Life changed and it’s constantly changing as a result. It’s been the thing that has paid the bills for the last 61 years. And it still lives on. It’s really amazing. That’s why I say there’s no such thing as old music. It’s either good or bad.”

The importance and legacy of Poinciana

Central to At The Pershing’s appeal was the song “Poinciana,” an exotic and haunting slow ballad written by Nat Simon and Buddy Bernier in 1936. “I was introduced to ‘Poinciana’ when I was a pianist for The Four Strings, a group founded by the late Joe Kennedy, Jr, who also was my conductor and friend for many years from Pittsburgh,” explains Jamal, who first recorded the tune for Epic Records in 1955. But it was the longer live version from At The Pershing that made Jamal’s name. Such was the song’s appeal that Chess released it as a single, and it soon rocketed up the US charts.

“Not often do we have instrumental hits, but ‘Poinciana’ is still being emulated,” says Jamal. “That particular record has been plagiarised and copied by many. It transcended all categories. And that’s very interesting because very rarely does an instrumentalist come up with a record like that. I can only think of Dave Brubeck, Herbie Hancock, and myself. ‘Poinciana’ goes on and on and on… it was a gift to me.”

Just how important the song became for the pianist is reflected in the fact that it’s been an ever-present feature of his live performances for over 60 years. He’s also re-recorded it many times. “I don’t tire of playing ‘Poinciana,’” Jamal says. “I do some different things each time we play it, and it’s a wonderful challenge.”

Ahmad Jamal’s piano style

Though he fell under the spell of several virtuoso pianists – he names Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, and Nat “King” Cole as key influences – Ahmad Jamal patented a unique and distinctive style. Its defining characteristic was his supremely delicate touch, resulting in crystalline, right-hand filigrees. Also, he found a very savvy way of using space for dramatic effect, which allowed his music to breathe. Unlike some jazz pianists, Jamal didn’t feel the urge to create a gushing, uninterrupted torrent of notes; he opted for a more conversational style with natural pauses between phrases.

From his very first records, released in the early 50s, Jamal soon acquired a rapt audience among the jazz community. Miles Davis was a big fan and covered several of Jamal’s tunes, including “Ahmad’s Blues” and “The Surrey With The Fringe On Top” (on the Workin’ and Steamin’ albums, respectively), and “New Rhumba,” recorded on the trumpeter’s Gil Evans-arranged orchestral album Miles Ahead, in 1957. “Miles was a great supporter of mine,” says Jamal. “We were both contemporaries, even though he was a little bit older. We were also neighbors. There was an attempt to get Cannonball, Miles, and I on record but it was not successful. When we were at The Pershing, he was downstairs in another room they built for music, so he was able to come upstairs and see my group.”

The recording of At The Pershing

The idea to record a live album in the lounge of the Pershing Hotel was Jamal’s own. He remembers approaching Chess Records’ boss, Leonard Chess, about it. “I went to his office on 2120 South Michigan Avenue in Chicago and said, ‘Len, I want to do an on-location recording.’ I never had any problems with him and had absolutely free rein with everything I did, so he said, ‘Go ahead, no problem.’”

Recorded across January 16 and 17, 1958, Jamal’s trio were captured playing 43 different songs. The pianist admits it was a mammoth task whittling several hours of music down to the 30 minutes or so required for a single album release. “It took me weeks,” he says, “but I chose the eight tracks very diligently.” Interestingly, Jamal didn’t include any of his own compositions. “I was very naive,” he laughs. “But, you know, I can’t argue with the American songbook. I neglected to put in my compositions, but the result was beyond my wildest dreams. It became one of the biggest records in the history of Chess.”

Jamal is keen to spotlight the contributions that bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernell Fournier made to the album. “They were two monumental players and were sought after by many,” he says. “I finally got them to join my group in the late 50s. Vernell Fournier was originally from New Orleans and became one of the most popular drummers in Chicago at the time. The way he played, people thought we had two drummers. It was a combination of what I did and what the two of them did which made At The Pershing a success.”

Best Jazz Pianists: A Top 50 Countdown

The 25 Best Chess Albums To Own On Vinyl

Best Blue Note Album Covers: 20 Groundbreaking Artworks

Such was their intuition that, on stage, the three musicians seemed to be communicating on a higher, almost telepathic level. Jamal puts it down to the long residence they enjoyed at The Pershing. “We were there for many, many months,” he says, “which led to a certain togetherness that can’t be captured, in my opinion, in any other manner. When you’re working together doing five sets night after night, you develop a cohesiveness and a musical cement that’s unequaled.”

Other gems

Though At The Pershing: But Not For Me was undoubtedly the pinnacle of Jamal’s time with Chess, his tenure with the label yielded other gems, including an orchestral album, 1959’s Jamal At The Penthouse, and a Latin American-themed ensemble piece, Macanudo, in 1962. Aiming to capitalize on the popularity of At The Pershing, Chess released a second album sourced from the original tapes, Jamal At The Pershing Vol.2, in 1961. There was also a plethora of other live recordings for the label, among them Portfolio Of Ahmad Jamal, recorded at Washington, DC’s Spotlite Club; Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra (where the pianist was captured at a Chicago restaurant that he owned in the early 60s); and Ahmad Jamal At The Blackhawk, featuring a performance from a popular San Francisco jazz haven.

Between 1956 and 1968, Ahmad Jamal recorded 21 albums for Chess via their Argo and Cadet imprints. He then signed to Impulse!, where he made four albums before joining the roster at 20th Century Records for seven years. There he gravitated to the electric piano and became an adherent of jazz-funk, with some of his tunes from that period being sampled by hip-hop producers.

In more recent years, he’s come full circle, returning to his beloved Steinway acoustic piano. And it was with that instrument that Ahmad Jamal made his name with At The Pershing: But Not For Me. It was a hugely significant recording that represented not only an important milestone in the pianist’s career, but also in the history of Chess Records and jazz in general.

This article was first published in 2019. We are re-publishing it again, today, on the anniversary of its recording. Listen to At The Pershing: But Not For Me on Apple Music and Spotify.