Before 1981, most of the people who’d ever heard of the Greek composer Vangelis were prog-rock diehards who knew about the one week he spent as Rick Wakeman’s replacement in Yes, and maybe fished his albums out of the import bins. Then he writes one ridiculously catchy tune, which became the main theme of Chariots Of Fire, joining the growing ranks of musicians-turned-film composers. Suddenly, millions of people who’d never bought an import keyboard album, or even a Yes album, had at least one Vangelis disc in their collection.

That’s one example of the unlikely crossover between the rock/pop world and movie soundtracks. We’re not talking about the artists who wrote an iconic song or two for a movie – sorry, Paul Simon and “Mrs. Robinson” – but the ones who actually rolled their sleeves up and composed a full-length score. During the 60s, very few pop artists were doing it, and the ones who did weren’t getting a lot of attention: Paul McCartney led the way by scoring the English comedy The Family Way in 1966, and George Harrison followed suit with Wonderwall two years later.

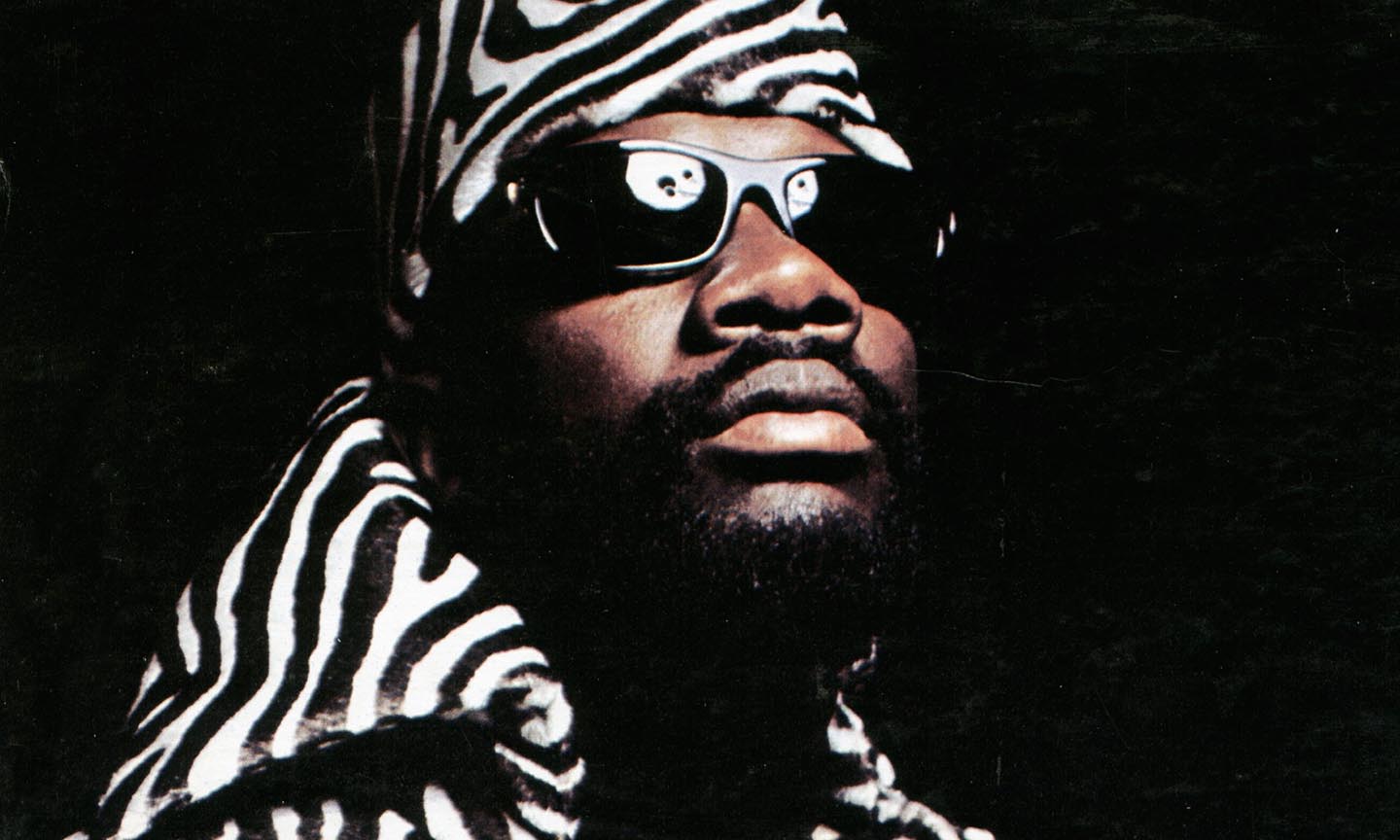

Soul heroes make their mark

The real game-changer was Isaac Hayes’ 1971 score for a funky private eye, which paved the way for many musicians-turned-film composers to follow. If you’re thinking Shaft, you’re damn right. Hayes’ mostly instrumental soundtrack (with, of course, a spoken vocal on the title song) was a masterful bit of composing, infusing progressive soul with some Mancini-like intrigue and, incidentally, sneaking the naughty phrase, “a bad mother” onto AM radio. The double-LP soundtrack sold like hotcakes and ushered in the heyday of the blaxploitation movie – and, disparaging as that term seems, it did connote adventure films with strong black heroes and heroines, disrespect for The Man, and killer music.

Curtis Mayfield also stretched out instrumentally for Superfly, though that score is remembered mainly for its classic songs “Freddie’s Dead” and “I’m Your Pusher.” Marvin Gaye’s all-instrumental soundtrack for Trouble Man practically explodes with ideas – and no wonder, since it was his first album after What’s Going On. Less remembered, but equally hip, were the soundtracks recorded by War (Youngblood) and James Brown (Black Caesar, Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off), and the two later ones by Hayes, Truck Turner and Tough Guys.

Unexpected masters of the form

The two artists who’d emerge as the biggest musicians-turned-film composers in the 80s and beyond – in both cases outstripping their considerable success as songwriters – were both major surprises. Danny Elfman was the leader of Oingo Boingo, a band whose national success never went beyond cult level. But they were quirky, whimsical, and big in LA, all of which was enough to catch director Tim Burton’s attention. Elfman’s offbeat sensibility became the perfect match for the fantasy films he wound up scoring: first a handful of Burton’s, including two Batman movies, then the three Spider-Man films, and, more recently, Fifty Shades Darker. Through it all, his style has remained recognisable. One could easily imagine Oingo Boingo doing the theme he wrote for The Simpsons.

Randy Newman’s skills for orchestration won’t surprise any fans who remember his first solo album. What is surprising is how much this long-time maverick has been accepted by the mainstream: when he did his first serious soundtrack, 1981’s Ragtime, he was still best known for “Short People.” The Dixie ambiance of that film was more reminiscent from his Good Old Boys album and later in the New Orleans-themed album Land Of Dreams. As a soundtrack composer, Newman keeps his incisive humor in check; he’s more a proud traditionalist whose music evokes the warmth of bygone eras. His biggest movie songs, including “If I Didn’t Have You” and “We Belong Together” (the respective Oscar-winners from Monsters, Inc and Toy Story 3) succeed in the near-impossible task of conveying warm sentiments without sounding treacly.

Elton John, Joe Jackson, and Eric Clapton

Elton John seems to have a mixed relationship with film soundtracks. The Lion King was one of biggest successes of his career, topping the US charts and going ten-times Platinum. But he didn’t take that as an occasion to launch a second career among musicians-turned-film composers. The soundtrack’s two megahits aren’t even regular parts of his live setlists, which are still devoted mainly to his classic 70s era. However, fans may want to check out two Elton soundtracks they probably missed. The Muse is the instrumental piano-driven album that many always hoped for; while The Road To El Dorado is an old-school, 70s-style Elton album by any other name.

Joe Jackson also failed to make a second career among musicians-turned-film composers – which is a shame, because the ones he did were so good. Logistically, 1983’s Mike’s Murder was something of a fiasco, since the Debra Winger thriller was re-edited before release and nearly all his music was removed. But the soundtrack album (now included on the deluxe reissue of his 1982 studio album, Night And Day) is essential if you love the Latin-jazz groove he was into at the time. Likewise, his overlooked soundtrack for Tucker, a film about an underdog car inventor who challenged the system – surely a theme Jackson could relate to – is full of invention and melody, a more accessible version of the classically-inspired work he’d do later.

Soundtracks also made for some odd couplings. Would you believe Eric Clapton and Mel Gibson? A strange one, but Clapton’s first serious soundtracking was for Lethal Weapon, and its two follow-ups, all done with saxman David Sanborn and the late keyboardist Michael Kamen (the ex-New York Rock Ensemble leader who was a key Clapton collaborator at the time). In truth, none of those were especially guitar-heavy or Claptonesque, but that wasn’t true of Rush, the one film Clapton scored on his own. There’s plenty of mean-sounding guitar on that one to fit a dark thriller about the narcotics underground (with a kingpin played memorably by Gregg Allman, no less). This was also where his hit “Tears In Heaven” made its debut.

Electronic producers

Lately, it’s been the cutting-edge electronic acts that have moved into soundtracking – and Trent Reznor making the move was only a matter of time. Since producing the soundtrack to Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Reznor’s been the go-to composer when a film needs some chilling atmosphere, such as David Lynch’s Lost Highway. Like Burton and Elfman, Reznor has formed a fruitful relationship with director David Fincher, scoring his moody set pieces that include Se7en in 1995, The Social Network in 2010, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo in 2011, and Gone Girl in 2014. More recently, Reznor and his long-time partner, Atticus Ross, created the chilling score for the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick PBS documentary series, The Vietnam War, and also reinvented John Carpenter’s Halloween theme tune for the 2010s.

When the Disney folks wanted to make a sleek modern update to the cyber classic Tron, they called on Daft Punk, whose Tron: Legacy score was full of future shock, sounding weightier than either the typical Disney soundtrack or the typical Daft Punk album. What’s clear is that, as long as the sound of pop music keeps changing, the sound of the movies will change along with it.

Looking for more? The 50 Greatest Film Scores Of All Time.