This interview was conducted in 2000 and first published a few years later. In honor of Sam Phillips’ birthday, we are republishing it again today.

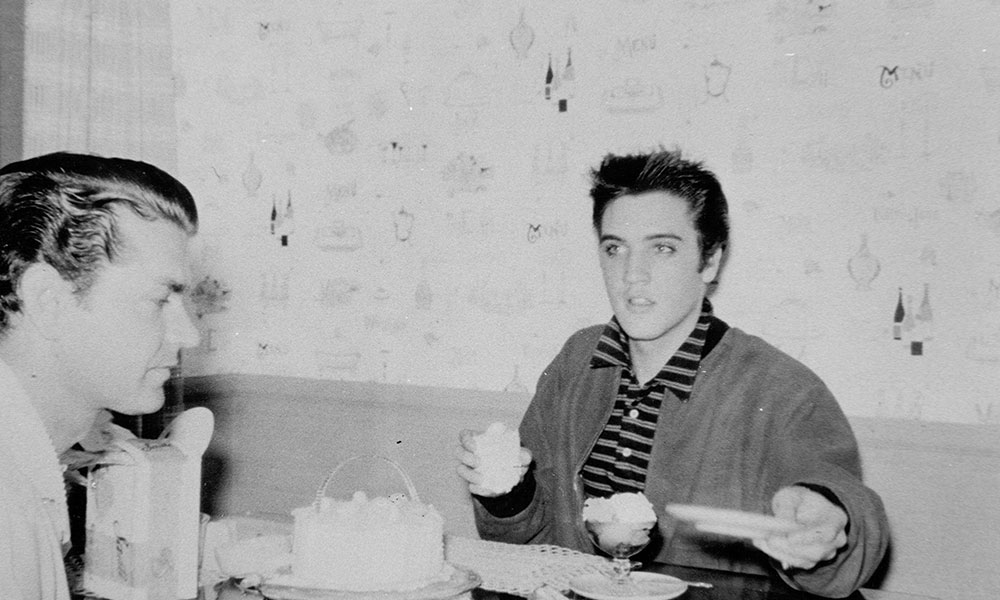

I was lucky enough to visit Sam Phillips at his home in Memphis while making a TV documentary in 2000. Sam was a gracious host, full of old-school Southern charm, and eager to talk about the blues and Elvis. A year or so later I had dinner with him and this was akin to going to church. Sam spent the whole meal preaching about music, southern life, and life in general. This interview just scratches the surface of his incredible life.

How did you get started in the music business?

Sam Phillips: I started in the music business when I was a child at home on the farm in Florence, Alabama, which is 150 miles east of Memphis. I became so interested in the blues, and back at that time, as a child (and I’m going back many, many years, back to the 30s and 40s) I sensed and felt being in being around black people and country people and desperate people because it was repressioned age, I picked up the idea that there was nothing I heard that was more entertaining, more attractive to me when I was six and seven years old, hearing black people singing whether it be in the corn patch or cotton field.

Of course, when I got to a little black country church, that was a whole different thing. I mean there was nothing in the world that was more inspiring than that, unless it would be the preacher. Black preachers were tough! It’s the church what makes the blues the most powerful force.

Then as a young person, I got a good job at WREC, a radio station in Memphis, Tennessee, and I left Florence, Alabama. And I worked hard to get that job because it was affiliated with CBS Network, a big network all across the nation, fed the big band from the skyway of the Peabody Hotel, the South’s biggest convention hotel. And here I was finally with a secure job, and you would think “Well goodness, what do you want to do fooling around with something here that all you’re gonna do is get criticized for it” – but the elements of the Blues and the associations that I had with black and white people, of the soul, made me understand that I heard that the world should hear.

I’ll brag on myself when it comes, nobody knew music better than I can when it comes to mixing it, getting it out of people, totally untrained, untried, unproven, but that was my cup, it totally was.

So basically when you say the blues to me, and regard to all of the genres of music today, you are saying that there is nothing – I mean, there is not any concerto, anything else – that hasn’t found its way back to the blues at some point in time. And when you get to the ideas of rock’n’roll; rock’n’roll was based on the actual feeling of letting go, that without the Blues and to a great extent now, and this was what makes it really interesting to me – is that country blues, white country blues, southern folk-type blues.

A good example of that to me, the greatest country blues singer in the world was the old Jimmie Rodgers, which maybe there’s not that many people know around the world as well as they do some of the more contemporary but he was singing all around the Watertank and Blue Yodel numbers 2 and 3. This guy connected with you. And he came from the same place that the black folks that were singing the blues. Jimmie Rodgers was a white man on a freight train, on freight line, and so consequently he got a little break with RCA Victor and put some work about.

Now I truly believe that when I got through recording like BB King and Ike Turner and Little Junior Parker, the Prisonaires and we all got along, I was looking to find a – and you’ve heard this before about me, I’m sure – I was looking to find a white man that could give the feel to his espousing words and song that didn’t copy, didn’t mimic, but was based on the same feeling, and I knew that feeling wasn’t that far apart. Because of poor white trash, as we were known to a lot of people, and “their nig__s,” as they were called down here, we were all in the same box together.

I can truly say to you, and take nothing away from the fantastic things that Martin Luther King Jr. and so many other good, good other black people did to try to get the division of whites and blacks, get that chasm closed, there is nothing, there is just simply nothing that has done more to bring us together both as races and as people in high-income brackets, in lower-income and so forth – there is nothing that has helped bring the world together more than music.

Music has done so much for us, and it started with the black and white blues in the South and has done, I’ll tell you, to make the idea of people living together, having fun together, a reality.

I’ve always loved the song, “Mystery Train,” and I wanted to know how it came about. How did you record it?

Sam Phillips: Actually Little Junior Parker cut it first. Elvis heard that, that’s one of the songs that bought him in the studio to lie to me and say “Hey, I want to cut a record for my mother’s birthday!” And that was just Elvis, he was just the greatest guy in the world. But Junior Parker had the idea for a basic rhythm pattern, but not much else. In the studio, we started talking about what this song could be about.

Back then it wasn’t aeroplanes so much as trains, and when you went and put somebody on a train, it was like “Oh man, I may never see him again,” kind of like it is with aeroplanes today. But that is the truth.

We just messed around with it a little bit and it just fell into that groove, I mean that is a perfect groove for that song. And you’d have said “Well, that’ll fit anything.” Later when Elvis came in and in talking with him, I found out the main thing that bought him finally to cut an audition record, was “Mystery Train.” Once Elvis cut it, there was one take on it, and you’ve heard this one take stuff before, this is it. And I said “Elvis, this is it.” So “Mystery Train” is just something that was so embedded in Elvis’ mind and everything that when he started to sing it, it was as natural as breathing.

And that does make a difference in how a record or performance sounds if it’s natural it’s going to be awfully hard to beat, I’m telling you. And there’s a lot of difference between it sounding natural like you’re just rolling off of a log, and that’s the feeling that you get with “Mystery Train.” And that’s why, and I didn’t always achieve it, but that natural feeling of “Man I’m enjoying this, please won’t you come and join me” type of feel, and all the records I cut, that was the thing that I tried to achieve. Despite my loving twisting the knobs and all that; I loved setting up microphones and everything about recording.

But I guess what was so interesting was the psychology of dealing with these people that had never been in a recording studio, an audition even for professional people is the toughest thing in the world to do, and especially if they think “Oh Lord, this might be my only opportunity, I can’t fail, I’ve got this opportunity more than I ever thought I was going to have in my life, I can’t fail.” Well, that’s the one thing that would make you fail!

How did you come to work with Howlin’ Wolf?

Sam Phillips: Well Howlin’ Wolf, Chester Burnett, is the guy. I’ve said frequently, is one of the most interesting people that I worked with. He had probably the most “God-awful” voice you ever heard. It was so distinctive and it was so pronounced that whatever you heard come out of his mouth, it had that magic charm of “I believe this, I just believe it.” And he wasn’t drunk, he wasn’t anything, and I’ve said this before, we didn’t have drinking on our sessions, not that I had anything against it because I like a drink myself, but I didn’t like wasting time on booze.

And I tell you, Wolf is the only person that I let drink on the session, and I’ve said this somewhat tongue in cheek, but not really, there was no way I could keep him from – and he, now listen, he never drank more than a half a pint of wine, OK. Well, the guy was about 6ft 5in and weighs about 280 lbs, and was all muscle.

When he locked into a song, it was just something to see. And that’s when you are drawing pictures with your mouth wide open, and that Wolf could do it, and there was nobody I worked with that I enjoyed working with more than the Wolf. I wish I could have kept him, but I lost him to Chess Records. I did the best I could and it wasn’t Wolf’s fault, it was just misinformation and that sort of thing.

But nonetheless, I was the one that got the Wolf truly believing in himself, and it’s unfortunate that I didn’t get to record the Wolf a lot longer because he would have been my entirely different approach to rock’n’roll. I got to take the Wolf, and I don’t know anybody else I could have taken, that I have recorded, before the Wolf or after the Wolf, that I could have done in such a manner that it would have attracted a lot of attention.

So you’re talking about a fantastic idea, every time the Wolf opened his mouth to me, I could hear every word that he said, whether he just moaned and he loved to moan, it always spoke tons to me, just incredible what that man had, and I guess the biggest regret – and I don’t have regrets because I’m so thankful for what little I did and have done and still do and all the blessings that have come my way – but I guess the one thing, if I had only one wish, would have been to work with the Wolf a lot longer, and to see what happened. And I think I know what would have happened, but I reckon the Wolf got the short end of the deal and simply because they didn’t know what to do with the Wolf. I did.

What did you see in Elvis, and what did you try and do with Elvis?

Sam Phillips: Number one, he was a raw as anything you’ve ever heard when he came into my studio. I don’t mean that he didn’t sing good. He sang good, he sang a ballad like “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin” and gosh, he was good. But what I heard in Elvis was, I knew the wrong thing would be for me to hear this beautiful untrained voice, unpolished, and it did need polish.

Here is a guy with a great voice, here is a guy that had something more than that to me. I’m not talking about looks; because there’s a lot of good looking men, movie stars, good looking singers, all of that. That wasn’t a criteria that I was going to use to find that white guy that could deliver that natural feel that you normally heard coming from black performers. Elvis, after we got to know each other and played around with things, and that happened a number of times, when I called up and got Bill Black and Scotty Moore to work with Elvis, Elvis never had a band, usually everybody that came near a studio, black and white, had some sort of a band, be it two, three pieces, whatever. Elvis didn’t. And he was a loner.

And so I thought “Hey man, I know who to use with him, that has a lot of patience, and that’s Scotty Moore.” And Scotty was the type of person, he was willing to try some things that were different. The reason I’m saying all of this is that it’s important to the decision that I made, and I made a decision to make him another “Eddie Fisher,” damn good singers on record, or Dean Martin or something like. He’d have been another good singer, good looking, entertaining guy, but his feel that came over to me when singing “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin,” the worst thing I could have ever done is to come out and cut a conventional song. I don’t care how good the ballad was, or how well we put it together, that would have been the wrong thing to do.

Like I said about Roy Orbison, even though I didn’t cut the big, big record sellers on Roy, if I had have come out with a ballad and Roy was a hell of a singer too, and it connects with Elvis, even though they were at different times at the studio, but I needed something to attract the young people,

So Elvis, when he came in, I mean it went through my mind, that this was my guy to attempt what I had been waiting all these years for, and that was in the bottom and the top and in the middle of my heart and mind and soul. As to whether or not we could pull it off, because I knew that there could be all kinds of opposition to what I was trying to do with Elvis Presley, with a guy who could sing like this.

But we did it because Elvis has that connecting power, because he felt that type of influence that I had been talking about from childhood, just like I did, from poor white childhood days and months and years in deep old Mississippi. And that’s why in my opinion, that was the second stage of Elvis’ birth in this world, was when he came to 706 Union Avenue and I heard him, that’s when he was truly born and was absolutely a part of the world of entertainment waiting, waiting to share it with the people the world over.

He had the ability to connect and let me tell you Elvis was not all that high on doing some of the things that I suggested that we try. I work with my artist, I wouldn’t tell them “Hey, you’ve got to do this” and you know, that’s a good way to waste his time or her time or your time and everybody’s time. I didn’t have time to waste, but I knew where I was going, whether I would get there or not, that was the challenge of the trip.

So I know that, and I know how much spirituality has to do with things that are so intimate as music and sound and words and just plain instrumentation of things and melodies that fly through your head.

You can say what you want, but it’s a fact, things that are done well, a rock’n’roll record or the greatest gospel song rendered you ever heard, you’re not going to do it the way it should be done if there’s not spiritual empathy in it. I’m sorry, it’s just the way it is.