In the 80s, a daring batch of guitarists answered the call of rock fans tired of endless shredfests and hungry for something different. Some were new faces, and some were 70s stalwarts reinventing themselves. But all of them embraced a new guitar vocabulary, one that focused on texture and tone instead of fancy fretwork and favored melodic surprises over an in-your-face onslaught, especially in the sacred space of the guitar solo. Often these aims were achieved with the embrace of new technology – everything from guitar synths to new digital effects and studio savvy. But ultimately the guitar anti-heroes of the 80s forged new paths for the instrument by blending brain and heart in equal amounts.

Time for a change

The idea of the old-school rock guitar god started in the late 60s, with blues rockers and psychedelic stringbenders alike pursuing ever-increasing standards of speed and dexterity. The approach undeniably birthed plenty of sonic thrills and shaped multiple generations’ musical mindsets, but after about a decade, the winds began to shift.

While large swaths of the rock mainstream would continue to embrace the idea of the guitar hero as technical virtuoso for years to come, the arrival of punk realigned a lot of minds in terms of musical values. The rock revolution of the late 70s looked askance at the old ways of doing everything, guitar solos included.

For the most part, the first burst of punk and New Wave decried the concept of the lead guitar stylist entirely. Players like Television’s Tom Verlaine (the Jerry Garcia of the CBGB set) were the exception that proved the rule. When Mick Jones went so far as to blast out a quick, unfussy flurry of licks on “Complete Control” from The Clash’s 1977 debut album, Joe Strummer immediately chased it with a distinctly ironic shout of “You’re my guitar hero!” so nobody would get the wrong idea.

Before punk even reached its peak, the first wave of post-punk was already rising, bringing with it a fresh way of thinking about the guitar. When John Lydon crawled from the wreckage of the Sex Pistols to build a new style from scratch with Public Image Ltd., he relied heavily on the six-string iconoclasm of Keith Levene.

The guitarist’s arsenal of future-focused techniques would increase exponentially over the next few years. But with the opening cut of PiL’s ‘78 debut, First Issue, the nine-minute aural apocalypse simply titled “Theme,” Levene was already leaving traditional melodic scales in the rearview and applying his effects-slathered sound almost exclusively towards thick, roiling textures.

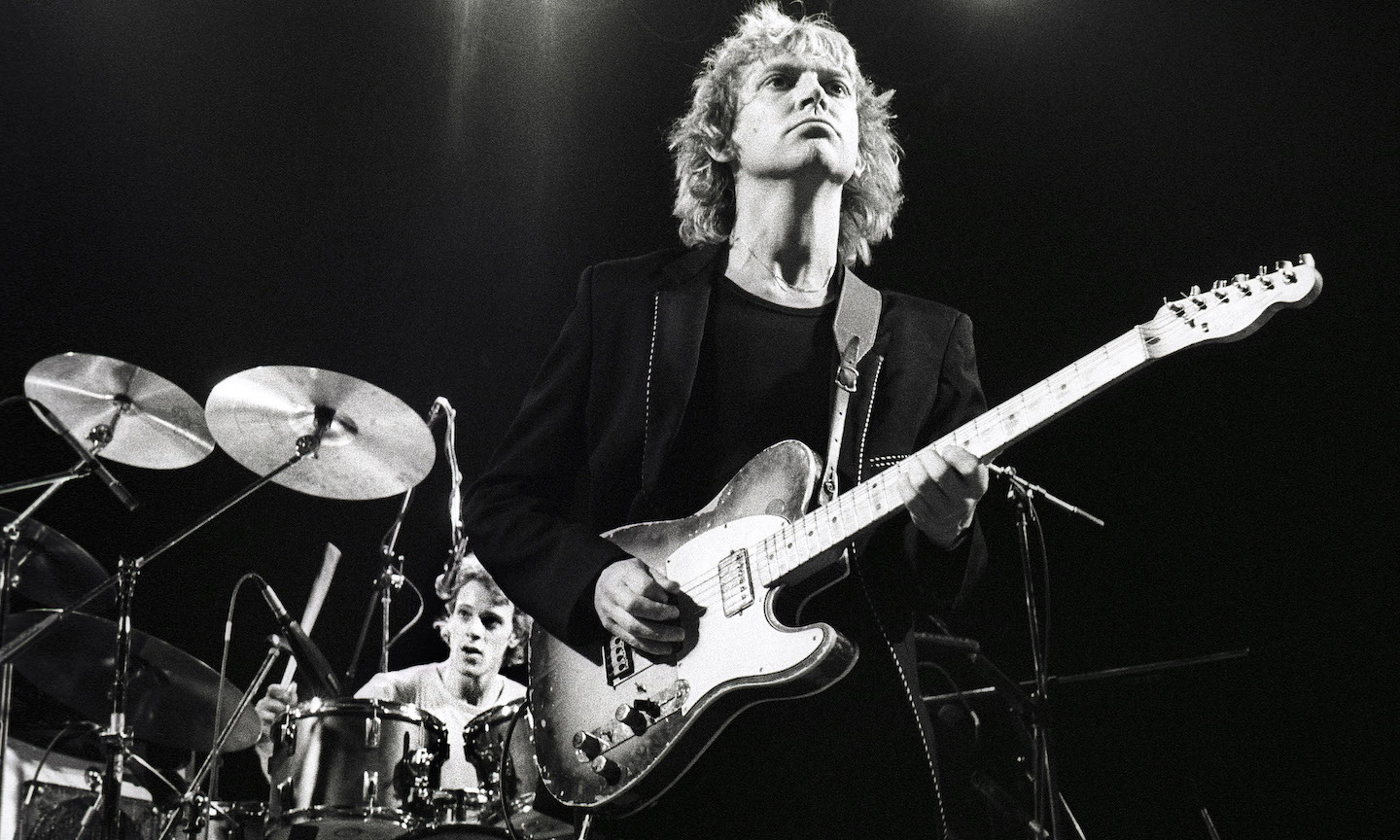

Around the same time, another early adopter was using post-punk/New Wave’s opening gambit as a springboard for innovation. Like Levene, Andy Summers of The Police was intensely influenced by dub reggae, but he was nearly 15 years Levene’s senior. He’d already been involved with the R&B of Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, the psychedelia of Dantalian’s Chariot, and even the jazzy prog exploits of Soft Machine, and he had plenty of “conventional” chops under his fingers.

But Summers was fascinated by the possibilities of abstract expression in his guitar playing. And though most of his work on The Police’s 1978 debut, Outlandos D’Amor, falls on the punky side of the band’s rock/reggae hybrid, you can hear the seeds of Summers’ future style on “Can’t Stand Losing You,” where he employs a phaser (and who knows what other effects) for a spacey statement that feels more like a time-lapse video of a flower blooming than anything in the rock lick lexicon.

By the time the 80s arrived, it was a boom period for rock guitarists who yearned to say things in a new way. Leading the pack was a 19-year-old kid from Dublin named Dave Evans, who would go on to conquer the world with U2 under his stage name, The Edge. U2 met the world at large on 1980’s Boy, on which The Edge, energized by punk but seeking something beyond it, started developing his signature sound — a highly finessed but resolutely non-flash style reliant on harmonics, feedback, and a heady cocktail of effects. His concepts would come to full fruition with the exotic vistas of The Unforgettable Fire and The Joshua Tree, but you can already hear it happening on tunes like the ominous “An Cat Dubh.”

Old Dogs, New Tricks

It wasn’t just the young guns who were redefining the language of the lead guitar at the time. As the brains behind King Crimson, Robert Fripp belongs on the Mount Rushmore of prog rock, but after the band’s breakup, his trademark gliding, sustained tones cropped up on records by David Bowie, Peter Gabriel, Blondie, and others, his solos adding atmosphere instead of the firestorm of notes that was well within his skill set. In 1981 he took the mindset further, first into an album by his short-lived new wave band The League of Gentlemen, and just months later, with a groundbreaking reboot of King Crimson.

There was about as much common ground between the 70s and 80s versions of Crimson as there was between Talking Heads and The Moody Blues. In fact, Fripp was working with another guitarist for the first time, one who had just helped Talking Heads reinvent their sound. Adrian Belew had brought a firestorm of invention to the Heads on their album Remain in Light, and working in tandem with Fripp on Discipline, he opened up his magic bag even further, letting a whole circus of sounds fly out.

Belew delivers a menagerie of braying elephants, roaring tigers, and seagull squawks, which share space with unearthly wails and tonal tornados, all enabled by his ample effects rig, guitar synth, and sui generis musical mind. With such a forward-looking sparring partner, the unceasingly inventive Fripp pushed himself even further. Without abandoning his predilection for knuckle-busting picking patterns, he leaned into the more painterly ideas at his disposal, sometimes creating placid counterpoints to Belew’s wild braying, but always operating like nobody that came before him.

Life Fripp, Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera became an art-rock guitar god in the 70s, creating some glam-tinged classics along the way. But he’d never really been a chops guy to begin with, and when Roxy retooled their sound and found a whole new generation of fans with 1982’s Avalon, Manzanera was at the center of the action. On hits like “More Than This” and “Take a Chance with Me,” phaser, echo, and chorus pedals became his companions as he created twinkling, pointillist constellations of sound that shimmered instead of shrieked, providing the perfect complement for Brian Ferry’s urbane croon.

Across the Atlantic, another 70s stalwart was giving his guitar solos a fresh coat of paint to push his band into the future. Rush spent a sizable chunk of the 70s coming off like a Canadian cross between Yes and Led Zeppelin, and Alex Lifeson accordingly developed a knack for unfurling furious streams of notes at an awe-inspiring pace.

But by the time Rush reached a new commercial and artistic peak with 1981’s Moving Pictures, Lifeson too was letting the zeitgeist flow through his Fender Strat (or Gibson 355, as the moment demanded). In place of his epic, machine-gun fire attacks, “Tom Sawyer” and “Limelight” – the songs that truly cemented Rush’s rock star status – featured concise solos prioritizing unexpected swoops, preternaturally deep bends, and a high-tension sustain, while still showing Lifeson’s technical prowess.

In the case of prog pioneers Yes, the departure of Steve Howe to form Asia left the door open to innovation, and in walked young gun Trevor Rabin. The new guitarist helped revitalize Yes, reshaping their sound for a new era (with aid from superproducer and onetime Yes member Trevor Horn). The gargantuan hit “Owner of a Lonely Heart” put Yes back on top, in no small part due to Rabin’s startling solos, full of serpentine, effects-soaked lines taking thrilling leaps from sonic cliffs and emerging without a scratch.

Mainstream rock’s last act

By the mid-80s, guitar mavericks like The Edge and Andy Summers had reached their full artistic height and gone from outliers to tastemakers. On the metal side of the fence, the need for speed would never subside, but it was no longer the only option on the menu. At the time there were probably almost as many kids woodshedding U2’s “Gloria” and The Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” as any of the usual classic-rock staples, and they were just as intent on getting the tone spot-on as they were about nailing the notes.

There were plenty of other 80s guitar antiheroes busting their way out of the box too. Besides all the aforementioned adventurers, the decade’s first half saw a bold batch of other pioneers pushing back against rock guitar convention, like The Pretenders’ James Honeyman-Scott, The Smiths’ Johnny Marr, R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, and The Durutti Column’s Vini Reilly, to name just a few.

The guitarists who once fought against the tide were now directing it to a new destination. Sure, the rock mainstream was overtaken by high-speed hair-metal gunslingers by the end of the 80s, but don’t forget which way Kurt Cobain was leaning in his approach to six-string expression even as he cried out, “Here we are now, entertain us!” as grunge drove the nail in hard rock’s coffin.